The Heroes Using Ancient Knowledge to Revive Chennai’s Water Ecosystem & Fight Flooding

Drought to floods, Chennai has been experiencing both. But this team of changemakers from IIT Madras, Care Earth Trust, Madras Terrace Architects and more are working on some unique solutions for its water woes.

Sekhar Raghavan’s story starts in the 1990s as a resident of Besant Nagar, Chennai. As developers paved driveways and compounds in this neighbourhood close to the seashore, Sekhar noticed that the level of water in the shallow wells fell and became brackish. Even borewells were beginning to run dry.

As a resident of the area since the 70s, Sekhar had valued easy access to high quality drinking water. His 6-apartment complex had its own shallow well and water percolated easily through the sandy soils, always staying just a couple of feet below the surface during the monsoons.

With the benefit of observation and study, he was convinced that the change in water was due to the many new infrastructural developments which, in effect, sealed the soils. This made the water stay on the surface before evaporating or reaching the sea.

The problem, in his view, could be addressed by harvesting rainwater locally, replenishing the aquifers which are both high up — using the soil’s water-holding capacity — and also deeper down in the rock crevices and caverns.

To bring in more public support, he began a door-to-door campaign in 1995 to convince the locals and the municipality that rainwater harvesting was vital. He promoted recharging the valuable groundwater aquifers rather than only using concrete tanks to store rainwater because without replenishing them, they became vulnerable to seawater intrusion which could be fatal to those water stores.

He argued for increasing the permeability of solid surfaces — allowing water to percolate into the soil around new and old developments — supplying shallow wells, and enabling deeper aquifer recharge with rainwater to support borewell extraction.

“This is how water was managed until the mid-19th century when Chennai largely relied on groundwater sourced through shallow wells,” Sekhar says.

A long road ahead

At first, Sekhar’s ideas fell on deaf ears. When he tried to talk to residents, the security guards turned him away. Interestingly though, they seemed to have a better understanding of the problem than their employers.

The better-off urban population didn’t make the connection between rainwater percolation and groundwater, nor did they recognise the severity of the situation. In any event, they saw it as the Government’s duty to supply them with water.

However, in 1998, he had a breakthrough – after 3 years of drought was Chennai’s ‘Ground Zero’ (when some went without water for days). The editor of the Adyar Times gave him space to write an article and include his phone number.

He began to receive questions from residents in the Adyar-Mylapore region seeking guidance on implementing rainwater harvesting measures.

His efforts got impetus in 1994, when the then chief minister of Tamil Nadu, J Jayalalithaa, instructed the Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority to issue a notification that required builders to show what provisions were being made for rainwater harvesting before planning a new building.

The notification increased awareness of water conservation needs. However, according to Sekhar, hardly any developers integrated adequate schemes. Enforcement was difficult. However, one of the few developers who did take notice helped develop a recharge well approach for replenishing aquifers.

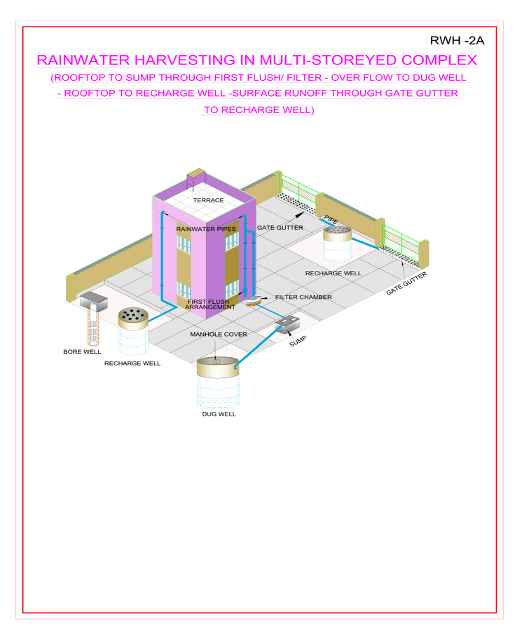

This involved diverting water from rooftops through pipes and then into the ground through 15-foot-deep wells of a diameter of 5 feet.

In the light of limited impacts, Jayalalithaa continued to be committed to action, strengthening the rules in 2002-03 which required both new and old buildings to have recharge and rainwater harvesting systems compulsorily. This time, the new municipal requirement also stated precisely what needed to be done – either divert rainwater into open wells or into the recharge wells.

How the efforts solidified

Around this time, in 2002, a US-based man named Ram Krishnan heard about Sekhar’s efforts and decided to back him. That’s how the Akash Ganga Trust was formed. Sekhar had been described as a lone crusader when interviewed by “Down to Earth” in 1998, but this was now to change.

He became the first trustee of the Trust and the director of the ‘Rain Centre’ that was originally established in Santhome. Now in Adyar, it is a demonstration of what can be done. He was pleased to have the value of the new centre recognised with the inauguration being attended by Jayalalithaa herself.

Sekhar adds that the results of the new municipal requirements soon became apparent. After a good monsoon in 2005, an Akash Ganga survey found that groundwater levels went up by 20 feet.

“My view is that rainwater harvesting should not be a bureaucratic or an academic exercise but a people’s exercise. That is why the Akash Rainwater Trust runs the rain centre so everyone can learn what can be done,” says Sekhar.

Drawing on the city’s heritage

However, continuing water stress demanded more extensive measures. To magnify the results, supporting other cities was also becoming a must.

In 2018, the City of 1,000 Tanks Consortium was formed, its name reflecting Chennai’s rich history of water management. It aimed to pilot and potentially scale systems this time, not only for harvesting rainwater, but also for recycling wastewater from sewage systems and purifying black & grey water using “nature-based solutions”.

How did the City of 1,000 Tanks come about?

Sudheendra, an architect from Madras Terrace Architects, a firm focused on eco-friendly architecture and executing urban water projects which played a key role in bringing about these changes, explains.

Following a global initiative – Water as Leverage (WaL) for climate resilient cities by Henk Ovink, Special Envoy for International Water Affairs, Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, a competition was announced for pilots in 3 cities in 2017.

Chennai, Khulna in Bangladesh and Semarang in Indonesia were identified as good cities to develop a model to solve the world’s pressing demand for water. A firm from the Netherlands, Ooze Architects, saw the potential to scale up action in Chennai.

They knew about the city and had worked with Shilesh Hariharan from the same firm as Sudheendra. They teamed up with a collective of architects and urbanists from the Netherlands & India, called it City of 1,000 Tanks, and developed an innovative proposal to restore the historical thousands of tanks which were originally present in and around Chennai.

The diverse multi-disciplinary team included urban designers, architects, engineers, as well as ecologists, policy researchers, engagement experts, and cultural and academic institutions from OOZE Architects & Urbanists, Madras Terrace Architects, IIT Madras, Care Earth Trust, Eco Village International, Capability Landscape, IRCDUC, Urayugal Social Welfare Trust, Rain Center, Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan Chennai, Chennai Resilience Centre, Paperman Foundation.

The team developed a strategy and a set of projects that offered a holistic solution to the problems of water scarcity, floods and sanitation, identifying the inter-relationship with the current way of planning or building cities.

They conducted multiple workshops and meetings working with WaL and the Government of Chennai.

The underlying message was that if all the rainwater that falls on Chennai is captured then there will be sufficient water, in fact more than is needed, to end scarcity. However, as 80% of the rain falls in around October-December in about 20 days, capturing it rather than flooding the city or squandering it to the sea is difficult.

As a result of this engagement, many government officials became aware of the need for a better water management system. Now, 50+ water bodies in and around Chennai have since been restored by the Greater Chennai Corporation, Public Works Department and many other NGOs, some with funds collected from Corporate Social Responsibility budgets.

Recycling Water – Nature-based Solutions

The second solution that the City of 1,000 Tanks advocated is more radical but also a part of Chennai’s heritage. This is better management of sewage wastewater, treating it in a decentralised manner using nature-based solutions instead of sending it out into the sea.

Banana and Canna are excellent examples of plants which carry out the treatment, ensuring the water can subsequently safely be allowed to infiltrate into the ground.

Recognising the potential, a pilot project was launched, funded mostly by the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management and contributions from the Goethe Institut, Max Mueller Bhavan Chennai and Wipro Foundation.

The scheme known as the Water Balance Pilot involves Little Flower Convent School for the Blind & Deaf. The team found that the campus of the school had three main water issues: sewage overflow, floods during monsoons, and drought during summer months.

They came up with a holistic approach.

Before sending the waste water to the plants, a settler (or a septic tank) allows all sludge to accumulate for about 24 hours and then an anaerobic digestion system is used to treat the sewage out of which, a secondary treated type of water arises. It is rich in nutrients – especially nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium which plants love and absorb to grow.

This is where the main element of the new form of wastewater treatment, called constructed wetlands, come into play. These wetlands, albeit constructed, mimic natural wetlands such as marshlands which are essential for retention, purification and infiltration of runoff surface water.

Similarly the treated water from these constructed wetlands is infiltrated in the ground in the neighbourhood which eventually finds its way back into the aquifer.

The results of the pilot programme were published in July 2023 and were encouraging with the water quality being good, better than the standard required for discharging it into the garden.This kind of treatment (quality of water let into the ground) involves water finding its way down through the layers of sand which means that the natural bacteria available in the soil cleanse the water and restore it before the water enters the local aquifer and thus the recharge is complete.

This forms a closed loop system and therefore enables self-sustaining communities in terms of water to start thriving. This is the basis for the future of water.

“The Water Balance project shows what WaL is all about, a game-changer approach; people-centred and community-led solving the world’s most pressing water challenges. The pioneer project in Chennai proves the value of community-led, nature-based solutions’ by design, that can lead the way ahead for upscaling and replicating – spreading from the city and the Ganga basin to the world. We can even put the UN Water Action Agenda into practice,” says Henk Ovink, first special envoy for International Water Affairs of the Netherlands.

“We have seen erratic unseasonal rainfalls, sometimes in excess of 100mm in a few hours and multiple times in a year. People are beginning to experience the reality of climate change and the awareness of the need for better water management is high. Now is the right time for those who own or manage land to invest in water initiatives to ensure large-scale storage sufficient to ensure the well-being of residents of the city,” says Sudheendra.

Lessons for the people and policy-makers

Sudheendra comments that in his view, the original legal changes brought by Jayalalithaa’s government were impactful.

“Though it was difficult to enforce this system in individual houses, all structures (residential, commercial or educational) built after this date have rainwater harvesting systems to some extent. Some of those who believed in the approach installed rainwater harvesting systematically with underground sumps which store large amounts of rainwater. This can be seen in Ramakrishna Mutt and Vivekananda Institution in Mylapore which proudly display the system,” he says.

Sudheeendra says that today rainwater harvesting is regarded in Chennai as a basic green measure. Many newspapers have written about the success in surmounting both the water shortage and addressing flooding challenges through this widespread practice.

He credits Sekhar for the role he played and values his bore log of the rainwater harvesting systems he has advised for, implemented or been a part of, providing data that shows a jump in the water table seemingly related to rainwater harvesting systems.

These stories show what can be achieved on one’s own and also as a collective. The outcomes are technological approaches as well as societal engagement methods that have the potential to be widely used particularly if backed by policy at a city or other level.

Both Raghavan and Sudheendra are of the view that with some policy nudges, these affordable positive actions can be mainstreamed. Challenges remain; for example, wastewater treatment by industries is already a legal requirement, but allowing treated water to be used to recharge the aquifers is not normal. If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change. Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution- By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike. Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

However, as Sudheendra says, good policy on its own will not create change. Regulations need both enforcement and buy-in. Architects, developers and the ordinary household must recognise the benefit of increasing access to local water supplies. Securing water supply for a “dry day” as one could say is vital. As these dry days become ever more frequent, with the extreme weather resulting from climate change, holistic local action is critical.

Written by Maya De Souza and Edited by Padmashree Pande

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167