We Built a Dream Eco-Estate BnB with 4000 Trees & Mud Homes Amid Kanha’s Wildlife

Inspired by his own travels, entrepreneur Ankit Rastogi decided to build The Surwahi Social Ecoestate Kanha in the national park, which is a sustainable paradise of mud homes, thousands of trees, local dining experiences, and more.

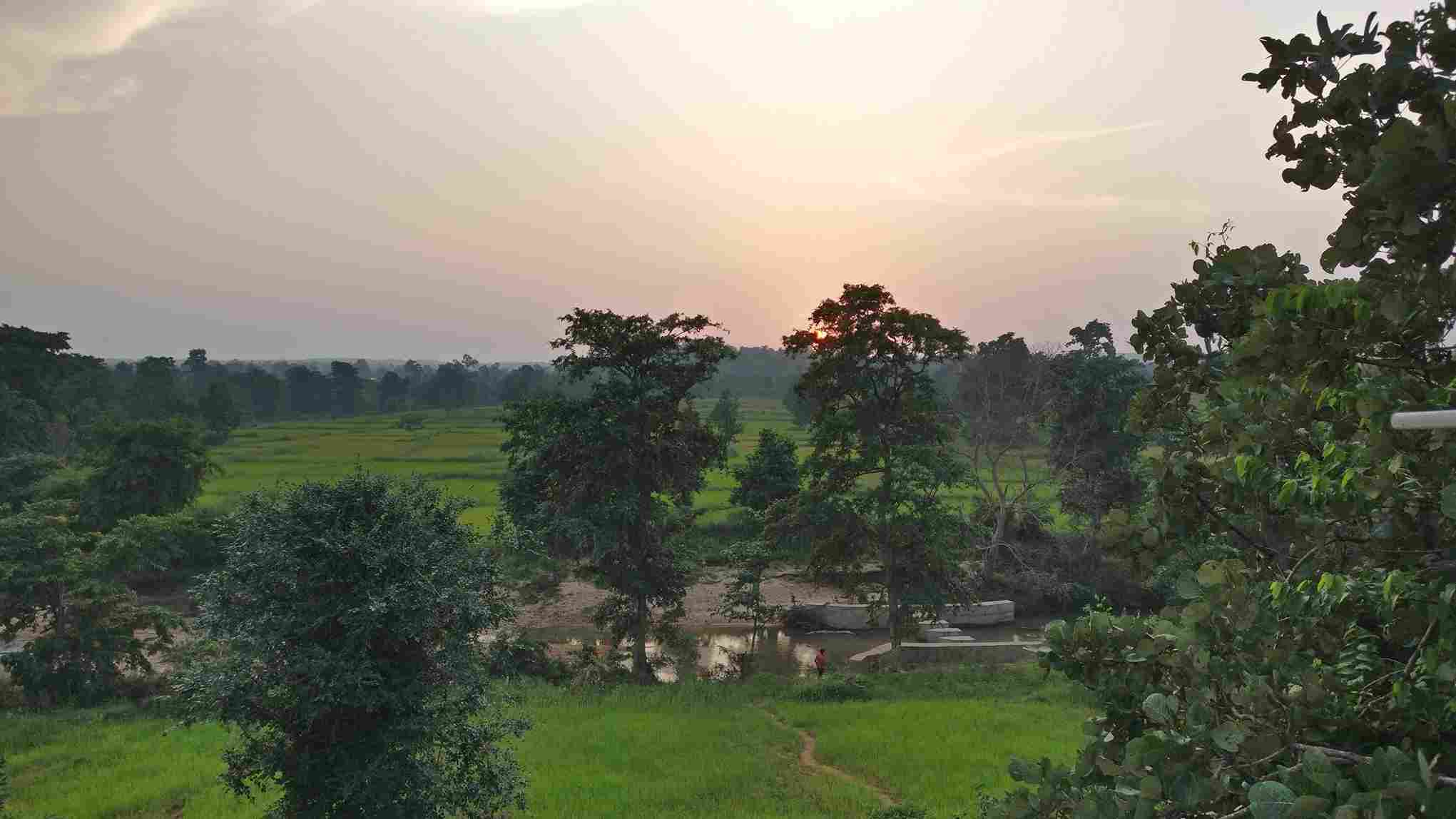

As yet another wintry morning dawns on the Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh, the forest comes alive with a cacophony of sounds of the native wildlife here — peacocks, langurs, tigers, vultures and antelope.

A beautiful symbiosis has always existed here between nature and the locals, a friendship dating back to 1879, when Kanha was declared a reserve forest. Fifty-four years later, it achieved the status of a sanctuary, and in 2000 was awarded by the government of India for being the best tourism-friendly national park.

Today, however, along with the famous safari trip, tiger spotting, leopard photography and more, guests have something more to look forward to — staying in a sustainable location in close quarters to the national park.

This sustainable tourism model is the work of Ankit Rastogi, a ‘travel enthusiast’ from Bengaluru.

It all started when he was working in a leadership position at a well-known travel aggregator company in 2015. Frequent trips across the country introduced Ankit to a side of travel he hadn’t witnessed much before — responsible tourism and homestays.

The Surwahi Social Ecoestate Kanha in the national park is his labour of love. Ankit says it took him “close to seven years” to design it with his team — Pradeep Vijayan, Narendra Patle, Mohan Shiva, Chainlal Gautam and Priyanka Rastogi.

And why choose Kanha National Park in particular?

“During my work-related appointments with the tourism department, I got a sense that they were leaning towards amping up tourism in this reserve. It got me thinking that if I could create an eco-tourism experience here, it would lead to the desired outcome,” Ankit tells The Better India.

The seeds for the project were sown in 2015, both literally and metaphorically, as the team first decided to lay focus on planting more trees in the area. In 2021, the work on this project officially saw the light of day.

Bringing the forest back to life

“We were never in a hurry to complete. We knew when we started out that it would take time,” says Ankit, adding that the first two years were only spent ideating, following which they began work on the forest.

Native seeds were sown on the 10-acre land, around which a fence was constructed. This would prevent animal encroachment as the tree cover developed.

“I learnt a lot during this time,” says Ankit. “One lesson was never to over-engineer. A forest has an immense appetite to come back, and instead of going overboard, simply letting nature take its course works better.”

Today, the result of that experiment is a land blooming with native trees such as sal, char (the tree that yields the dry fruit chironji), bamboo and more.

“Though sal was a common tree in Kanha, it wouldn’t grow on our side of the Banjar River. People would often say “Banjar ke us par sal nahi hai (There is no sal on the other side of the Banjar river). But we have managed to grow them,” says Ankit, adding that the land presently boasts 4,000 trees.

While the forest was left to grow on its own, Mohan Shiva, chief architect of the project, focused on the construction of the main building that would, in the years to come, welcome tourists who flocked to the national park.

Repurposed wood, zero-discharge toilets and more

Mohan highlights the design philosophy of the project that dodges the usual trends and instead borrows cues from sustainable architecture

“We used local materials and worked towards a spatial design in order to create a ‘sense of community’. The structure is made with mud and stabilised with cement and lime that render it strength and efficacy to survive wet conditions. The foundations effectively utilise murum (a local term for highly gravelly soil found in Kanha),” he says.

He adds that the pillars of the homes are built using old wooden logs called mayals, which are abundant in the village, as people who previously lived in kachcha homes are now moving to pakka ones. Meanwhile, the roof of the homes is laid with old country tiles kavelus, which act as the insulation layer and are laid upon tin sheets.

And the spaces are as aesthetic as functionally good.

A rainwater harvesting system is present on the roof spanning an area of 1000 sq ft. “It resembles a funnel system, which eventually drains into the pond, and when the pond’s capacity is met, the water goes into the well and recharges it,” explains Ankit.

He adds that the area around the pond — known as satkon owing to its heptagonal shape — lets guests relax and enjoy the view.

The principle of water conservation is a highlight at Kanha. This is reflected even in the zero-discharge toilet that uses minimal water.

“The toilet works on the principle of evapotranspiration. Once the person washes up, there is a tube that leads to an 11 ft pit in the ground, filled with rubber tyres and lined with gravel and broken bricks. The coarsest material is at the bottom while the finest is at the top. On top of the pit, there are banana plants, the roots of which go into the pit,” explains Ankit.

He adds that the waste is broken down in an anaerobic manner, as it travels through the tube, and microbes are released in the process. However, due to the length of the tube, no pathogens are left by the end of the journey and hence the resultant material is a great fertiliser for the bananas.

Ankit credits Marta Vanduzer-Snow, director of Safalgram, who extensively helped the team when it came to ideating for the zero-discharge toilets. Marta has been working in the villages of Uttar Pradesh promoting rural development and innovation.

Pradeep Vijayan, co-founder of the project, says that every aspect of the Kanha space has been designed keeping sustainability and responsibility at its core. “One needn’t dilute the premise of taking care of Mother Earth while engaging in new projects.”

He goes on to say that a pivotal point in their project has been to empower the locals. This can be seen in the array of activities that they arrange for guests.

Spot tigers by day, dine with the locals by night

The experience that the team has curated at Surwahi Social Ecoestate Kanha is aimed at providing guests with an “authentic” stay.

“We have a network of a few locals who host guests for lunch or dinner. On the designated day, we take guests to these homes where they can relish a range of local dishes such as saag, greens grown in the gardens, a dish made with leaves of garlic and ginger, and the hit favourite arbi,” he says.

In addition to this, guests can also take walks to the neighbouring pottery village Boda, visit the Chalukya Temple where a local artist Baldev sculpts on stabilised mud, and spend time at a park made of old tyres.

Whilst curating these experiences, the team has kept accessibility in mind, they say.

“We made sure there are ramps for wheelchairs and everything is in a single line without height variations. This was tough to ensure considering it’s a wildlife area. Even the switches in the commodes are at a low height,” he adds.

All of these features have transformed the Ecoestate into a mini eco-friendly world that has something for everyone.

Miles away in the main city, while yet another chaotic daily routine begins, at the Kanha National Park, nature unfolds in its own ways.

And it has never been more beautiful. If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change. Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution- By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike. Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

Know more about the project here.

Edited by Divya Sethu

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167