Duo Behind a 6-Year-Long Crusade To Uncover Loopholes in India’s Medicine Manufacturing

As the WHO raised an alert for cough syrups manufactured in India that led to the death of 69 children in The Gambia, authors Dinesh Thakur and Prashant Reddy discuss their years-long crusade to highlight the glaring loopholes in medicine manufacturing in India.

Trigger warning: Descriptions of illness, death of children

Two-year-old Fatoumatta was among the 69 children who died as a result of acute kidney failure in The Gambia, in a series of such cases since July this year. Her father said he took her to the hospital after she developed a fever. Here, she was diagnosed with malaria and prescribed a syrup.

She was dead within the week.

In an interview with Africa News, her father recalled, “She could not eat anything and was oozing blood from her nose and mouth….At some point, I was praying for God to take her life.”

These deaths were linked to four cough syrups manufactured by Indian firm Maiden Pharmaceuticals, based in Sonepat, Haryana.

Earlier this month, the World Health Organisation (WHO) identified these drugs as Promethazine Oral Solution, Kofexmalin Baby Cough Syrup, Makoff Baby Cough Syrup and Magrip N Cold Syrup.

WHO stated that the syrups were found with “unacceptable amounts of diethylene glycol (DEG) and ethylene glycol”, and expressed concerns that while these were only identified in The Gambia so far, they could have been “distributed…to other countries or regions”.

At least 70 children have died in #Gambia ?? after ingesting a cough syrup that had been made in #India ?? according to the @WHO

The incident is shaking the reputation of medications produced in India, often considered the pharmacy of the world. pic.twitter.com/SKzYjhdaYN— FRANCE 24 English (@France24_en) October 20, 2022

Resultant investigations, including a report by The Tribune, claimed that Maiden had “forged test reports of raw materials such as propylene glycol”. Their investigation also showed that the syrups, made from the same raw material, allegedly “showed different expiration dates” and that the firm “did not have the facilities to test the raw material”.

Even those who do not know the intricacies of drug manufacturing and regulation in India would be alarmed at how a country regarded as “the world’s pharmacy” could let drugs pass with so many red flags.

This becomes even more concerning when we understand that this is not the first such case, by any means, that innocent lives have been put at stake due to dubious manufacturing practices.

“In 2020, cough syrup laced with high amounts of DEG caused the death of 12 children in Ramnagar. As many as 33 children died after receiving cough medicines contaminated with DEG in Gurgaon in 1998,” noted The Lancet.

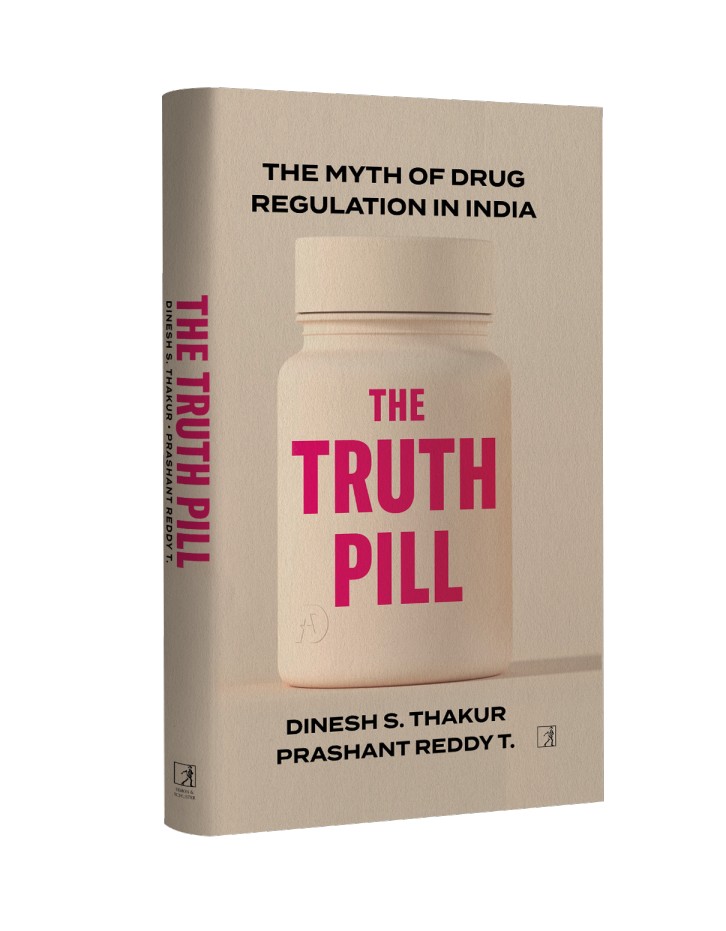

And in their book The Truth Pill: The Myth of Drug Regulation in India, authors Prashant Reddy T and Dinesh Thakur highlight many other such cases as well as how rules, regulations, and laws surrounding quality checks and drug manufacturing in India have been flawed, misused, misinterpreted or even ignored.

The book, says Thakur, is “an earnest effort…to educate our fellow men and women about the truth and reality of our drug supply”.

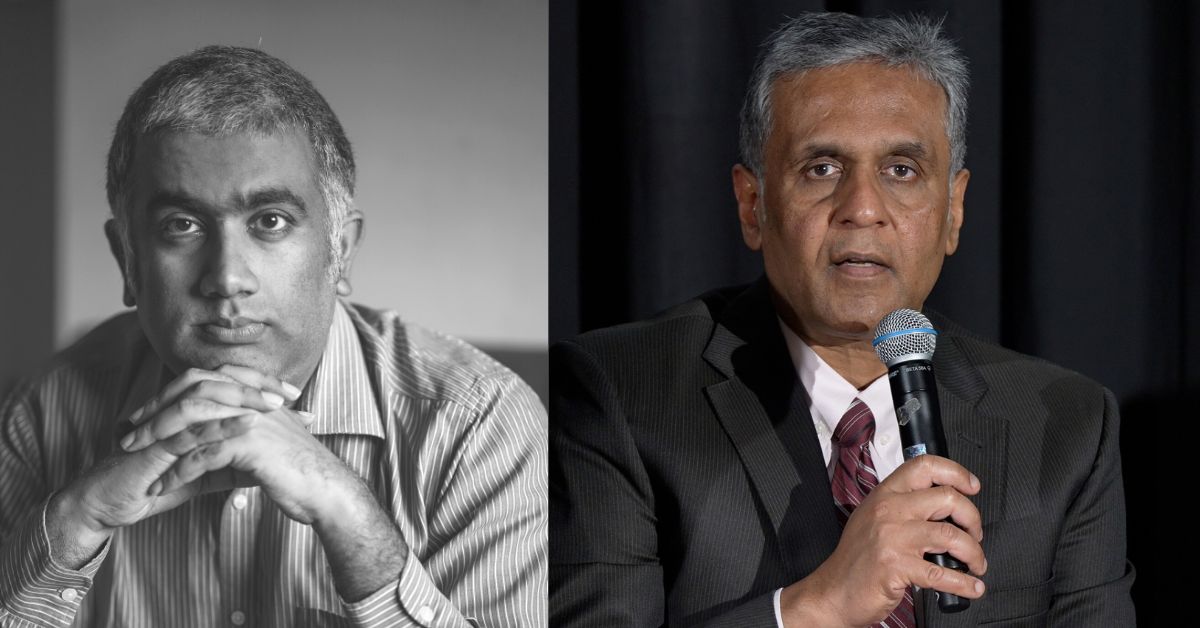

And the authors are no novices when it comes to this issue.

Thakur is a public health activist regarded as a “pharma crusader”, most notably for exposing his former employer Ranbaxy Laboratories for its failure to conduct proper safety and quality tests, as well as for falsifying data to receive approval for generic drugs.

“I went to school at Osmania University for my Bachelor’s in Chemical Engineering and then to the University of New Hampshire for my Masters. I was employed by Bristol-Myers Squibb for eleven years before coming to work in India for Ranbaxy. The rest is history,” he tells The Better India.

Thakur served as the director and global head of research information and portfolio management at the firm. With his manager Dr Raj Kumar, he reported his findings of scrupulous practices, first, to the board of directors at Ranbaxy, and later — after the pharma company refused to take action — to the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA).

Thanks to Thakur’s efforts, in 2013, Ranbaxy USA Inc pleaded guilty to selling adulterated drugs, failing to report drugs that didn’t meet specifications, and falsifying statements to the government, among others. The company paid a whopping $500 million to resolve the claims, which was at the time the largest financial penalty paid by any generic drug maker in the US for violating FDCA norms.

Meanwhile, Reddy is a lawyer with a keen interest in intellectual property law, drug regulatory laws, and transparency laws.

After completing his degrees from NLU and Stanford, he practised as a lawyer in IP litigation teams across New Delhi, worked as a research associate, and taught intellectual property rights and administrative law. Since 2020, he has worked as an advisor at a patient advocacy group set up by Thakur and also serves as a director for the Thakur Family Foundation Inc, an organisation that funds research on public health and civil rights in India.

About his decision to give up a career at a law firm to join Thakur’s advocacy, he says, “Well, it is not every day that you get an opportunity to work with a whistleblower on an issue as complicated as drug regulation. By the time I started working with Dinesh, I had some experience in dealing with drug regulatory issues while practising law, but even I was not prepared for all that we uncovered during the course of writing The Truth Pill.”

The ‘pharmacy of the world’

The book makes shocking yet eye-opening revelations about loopholes in drug manufacturing in India, tracing the history of medicine from pre-colonial and colonial times to its present-day status, how “much of drug regulatory law has been written with the blood of citizens who died in hundreds”, lack of accountability, and many such gaps that have more or less been left unaddressed.

It also highlights that since independence, India has seen five cases of DEG poisoning, yet, the situation remains unchanged.

While other countries such as the US learned from the first such instance to overhaul existing laws and make way for better regulation, India has been unable to do the same. The problem, they say, lies with not only regulation but also its enforcement, in that there are many factors and loopholes that lead to little repercussions for scrupulous practices.

But the most heartbreaking aspect highlighted is that those who suffer the most are the poorest of the poor, and more importantly, children, whose bodies are small and not equipped to deal with the serious health repercussions of such drugs.

“People who were affected by this atrocity didn’t even have the vocabulary to articulate what they thought was wrong and [why they] suspected it.” Dinesh Thakur

Though the book has been years in the making, its release in October this year rather morbidly coincided with the incident in The Gambia. “[This] apathy exists because there is zero accountability,” Thakur says. “Take this recent case….has there been even one press conference? Where is the outrage from the people of the country?”

Explaining what prompted them to write this extensive analysis of drug regulation, he says, “Prashant and I spent a lot of time developing a set of legal arguments, which we then took to the Supreme Court in the form of two public interest litigations (PIL). Unfortunately, the court thought the issues we were raising and the prayers we were asking were ‘academic’.”

He continues, “After exhausting both administrative and legal remedies, the only other option that was available to us was to educate the people of this country. Hence, this book.”

Because Thakur is an OCI (overseas citizen of India), he did not have the right to file RTIs. Hence, much of the research was led by Reddy and his team of research assistants.

“We also relied on the reports of the Parliamentary Standing Committees, judgements from Courts of Judicial Magistrates and High Courts and a historical record of debates in the Constituent Assembly before [India] became independent,” he explains. “Our past experience was relevant in the way we analysed the data we secured.”

Reddy notes, “Over the years, we have finessed our RTI skills. Dealing with regulatory authorities is not very easy, which is why instead of depending only on regulators for information, we tapped into the e-courts database to also try and understand how these courts proceeded through the judicial system.”

Thrilled to announce that my book with @d_s_thakur published by @SimonSchusterIN is available on Amazon for purchase from today. It is a deep dive into the history and myth of drug regulation in India.THE TRUTH PILL: The Myth of Drug Regulation in India https://t.co/Ei8orvlI5h— T. Prashant Reddy (@Preddy85) October 10, 2022

Behind the scenes of medicine manufacturing

Among the glaring inconsistencies highlighted in The Truth Pill was the status of regulation in Himachal Pradesh, the ‘pharmaceutical hub’ of the country.

For instance, the authors reported that the Composite Testing Laboratory in Solan had just one HPCL (High Performance Liquid Chromatography) machine that was over 16 years old. HPCL machines are instrumental in separating, identifying, and quantifying each ingredient in a drug sample, and assessing whether the drug dissolves as intended. Even Delhi had only one such machine, which was bought in as early as 2004.

Moreover, the number of drugs tested in each state was abysmal, to say the least.

“For example, West Bengal, which has a population of 90 million, tested just 2,637 samples between 1 January 2016 and February 2022. In the same period in Delhi, [which has] a population of 19 million people, drug inspectors sent merely 3,433 samples for testing — of these, the laboratory operated by the Drugs Control Department of Delhi claimed to have tested only 2,610 samples. Bihar, on the other hand, with a population of 128.3 million people, tested merely 14,103 samples during the same time period,” the book revealed.

The book also traces how, despite a large number of drugs found to be NSQ (not of standard quality), prosecution is lacking in most such cases. The authors opine that prosecution guidelines themselves tell drug inspectors and regulators to not prosecute unless it is “the last resort”, in gross violation of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940.

Do you know whether the medicine you are consuming is clinically tested for safety & efficacy?

Is there enough data in the public domain to ensure that consumers of medicine can exercise their human right to know what they are consuming?

1/n pic.twitter.com/7NE9sBRjoL— Dinesh S. Thakur (@d_s_thakur) October 25, 2022

Thakur says, “We use the government’s own data to make our case, because the prevalent narrative, as we describe in the book, is that the pushback comes in one of two ways.”

He elaborates, “First is to accuse anyone demanding accountability as a foreign agent trying to besmirch the reputation of the country as the ‘pharmacy to the developing world’ and second, in the forms of threats and intimidation.”

‘Just two voices among many’

In terms of what can be done to rectify and reform India’s drug regulatory system, the authors opine that the approach needed must be multifold.

The first thing to do, they say, is accept the gaps in the regulatory framework in the first place as more than just “a conspiracy theory”. They also ask for “citizen advocacy and intrepid journalism”, a larger focus on public health than only economic growth, a more centralised approach to regulation with democratic accountability, and empowering citizens with information and the right to participate.

Thakur notes, “We hope everyone reads the book. In order to make a cogent argument, one needs to be armed with data. The book provides this data. We also hope that people begin to demand more accountability from their elected representatives when it comes to the provision and the quality of our healthcare.”

On the same day as the launch of their book, the authors received a notice from the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) threatening legal action for their comments regarding drug regulation and the alleged role of the authority in The Gambia incident.

Thakur says, “We stand by everything we said in the book. It is substantiated by the Government’s own responses to over 400 RTIs. We have made all our primary research public. It is available in a searchable database. We have already responded to the CDSCO’s legal notice [and] explained the basis of the statements we made, and pointed out where they took our comments out of context.”

While Thakur and Reddy are leading a renewed interest in the conversation around drug regulation in India, the activist says they are “just two voices among many”.

“As we list in our book, there have been others who have tried to raise this issue in the past, only to face retaliation and retribution….Transparency and accountability are two key pillars of good governance.”

Reddy notes, “One of our key demands is for greater transparency through proactive publication of inspection reports, test reports, etc. Once this information is easily available we expect journalists and/or ordinary citizens to follow the issue more consistently and put pressure on the government.”

Thakur says, “Our biggest learning in this process has been to persevere. This is a long game….Our bureaucracy exists to frustrate any demand for accountability from the people of the country. The only way to make it accountable is to demand transparency and hold them accountable for the decisions they make, especially those that are not in the interest of the citizens of this country.” If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change. Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution- By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike. Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

You can buy The Truth Pill here. This is an affiliate link. If you purchase the book using this link, The Better India will get a small commission.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

Sources:

The Truth Pill: The Myth of Drug Regulation in India by Dinesh Singh Thakur and Prashant Reddy Thikkavarapu

Spurious drugs: Maiden Pharma ‘forged’ raw material test reports: Written by Bhartesh Singh Thakur for The Tribune, Published on 15 October 2022

Sharma, D. C. (2022, October 22). Cough syrup deaths expose lax drug regulation in India. The Lancet. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)02026-8/fulltext?rss=yes

Pharma crusader Dinesh Thakur takes India’s drug regulators to court: Written by Zeba Siddiqui for Reuters, Published on 7 March 2016

India must act on drug adulteration – lives around the world are at stake: Written by Dinesh S Thakur and Prashant Reddy Thikkavarapu for The Guardian, Published on 17 October 2022

‘The Role Of The Regulator Is To Protect The Public, Not Pharma Companies’: Written by Kavitha Iyer for Article 14, Published on 19 October 2022

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167