How a Grass Cutter’s Child Became Indian Cinema’s First Dalit Woman Actor

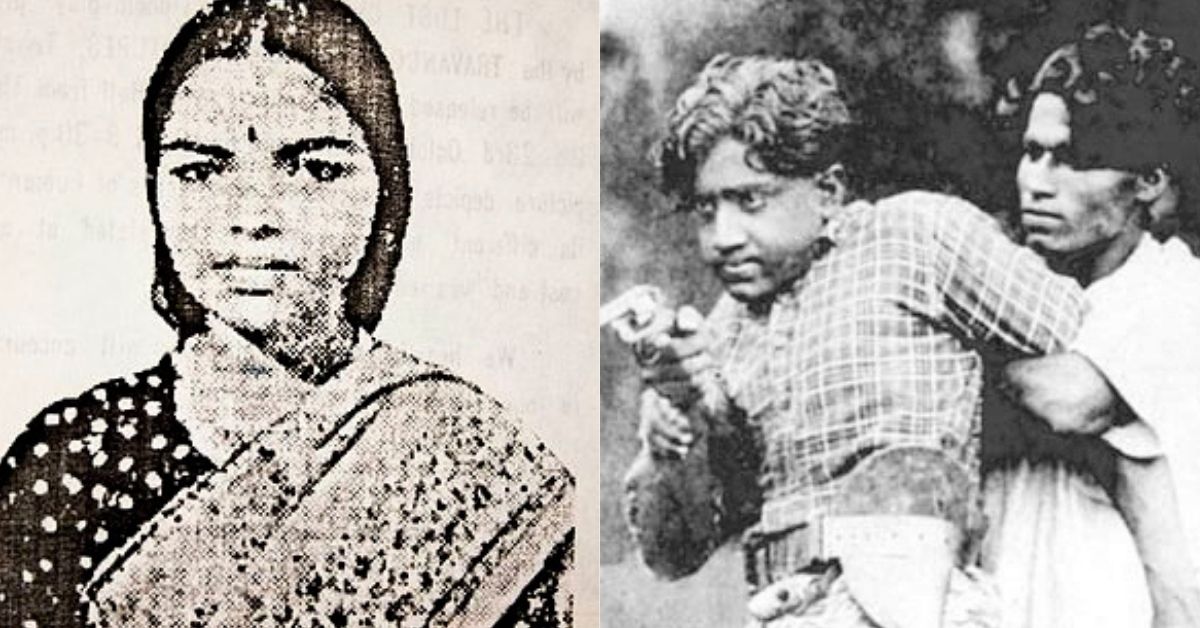

P K Rosy, Malayalam cinema's first woman actor and Indian cinema's first dalit actress, attracted the fury of many caste Hindus, who forced her to flee her state when she essayed the role of an upper-caste woman in Vigathakumaran, the first Malayalam feature film. She received recognition for her fearless work decades later, particularly in 2019, when the Women in Cinema Collective named their film society after her.

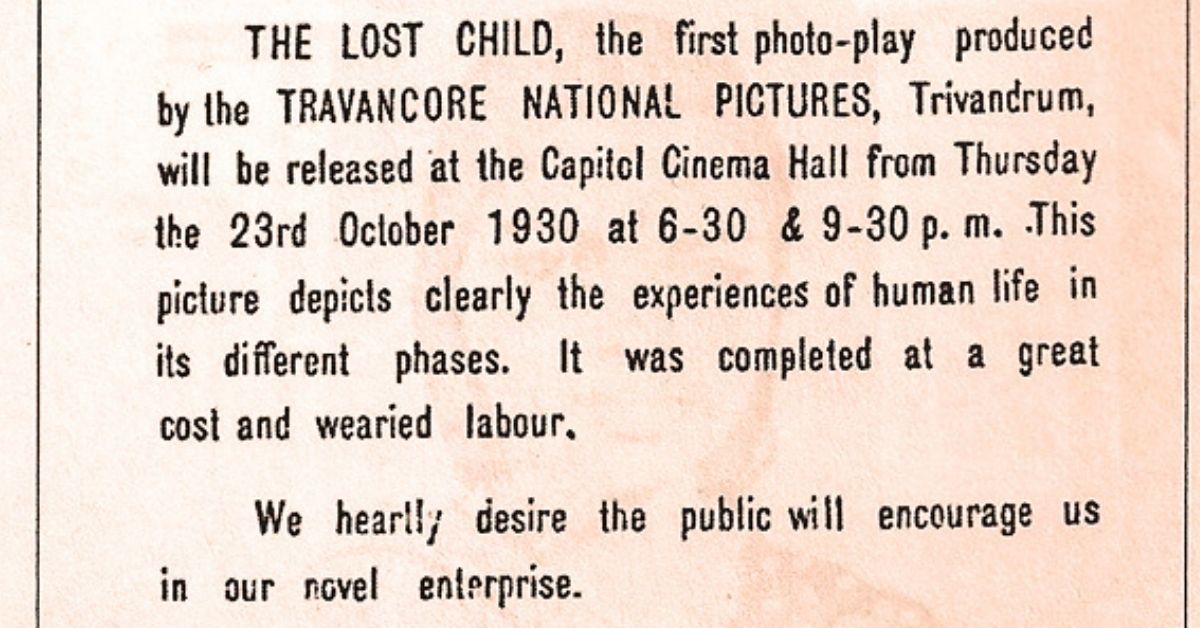

In 1930 (some say 1928), J C Daniel, known as the father of Malayalam cinema, directed and starred in Vigathakumaran (The Lost Child). The story was about Chandrakumar, who goes missing, and is accidentally reunited with his family years later. The movie led to many firsts — it was the first Malayalam feature film, and saw the industry’s first woman actor, and Indian cinema’s first dalit actress.

Vigathakumaran is now a lost film, with no known copy currently existing. Only one frame from the movie remains. Likewise, many aspects related to the movie remained forgotten until recently, including the fate and legacy of the film’s lead actress — P K Rosy. In 2019, the Women in Cinema Collective (WCC), an organisation for women who work in the Malayalam film industry, launched a film society named after Rosy, which finally brought her long-forgotten story to the forefront.

Who was P K Rosy?

P K Rosy was born to Paulose and Kunji in 1903, in Nandankode, Trivandrum. She belonged to the Pulaya community, who were considered untouchable and formed one of the major social groups in modern-day Kerala and Karnataka. After her father’s demise while she was still quite young, Rosy spent her time working as a grass cutter.

Some accounts say she was born as Rajamma, which became Rosamma (and subsequently Rosy) when her family converted to Christianity. Others claim her name was changed by Daniel because he wanted her to have a more “glamorous identity”.

The Pulaya community is known for their affinity in craftsmanship and basket-making, as well as for their tradition of oral storytelling and folk songs. Rosy, too, had an unquenchable interest in the performing arts, particularly the Kakkarissi Natakam, and was enrolled in a drama company in Trivandrum. Of course, at this time, women performing in theatre were considered akin to prostitution, and for a woman of a lower caste to do so was even more unprecedented. Rosy continued, despite her family’s resistance.

It was during a Kakkarissi performance that J C Daniel first discovered her. She was chosen to play the role of Sarojini, the woman Daniel’s character falls in love with. Particularly, she was essaying the role of an upper-caste Nair woman. The Big Indian Picture said that in an article written in 2005 for Chithrabhumi, Rosy’s nephew, Kavalur Krishnan, said, “Rosy shot for the film for 10 days and was paid a daily wage of Rs 5.”

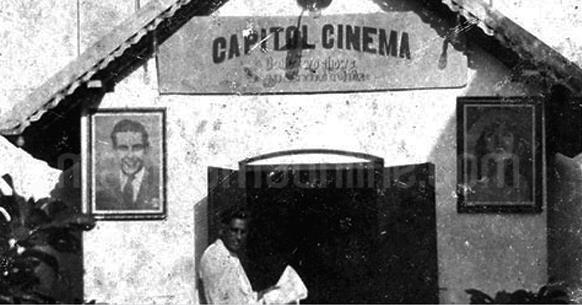

There are two release dates proposed for the film — 7 November 1928, and 23 October 1930. The movie was screened at Capitol Theatre in Trivandrum. Madhu Kevlar, another nephew of Rosy’s, said that at the time, south Travancore practiced untouchability stringently. He said, “A person from a lower caste couldn’t even walk on the road at the same time when someone from a higher caste was on it. And those were the times in which she went to act in films.”

The fury of upper castes

Daniel anticipated the possible backlash from the audience, and asked Rosy to stay away from the premier event. Regardless, she went to the theatre with a friend. Madhu said that one Malloor Govinda Pillai, an eminent lawyer of the time, was to inaugurate the film, but refused to do so till Rosy left. So Daniel asked her to leave, and come back for the next show instead.

The audience, consisting of caste Hindus who were already disgruntled at the portrayal of a Nair woman by a Dalit, were pushed off the edge when Daniel’s character kissed a flower in Rosy’s hair. There was massive furor, in which the screen was torn by the angry mob.

Journalist Kunnukuzhi Mani, who has been credited as the first person to try and dig out Rosy’s history, was quoted in the TBIP article: “There was a ruckus and they (the audience) destroyed the screen. A mob came to her house and began throwing stones at it. Then two policemen, whom Daniel had requested the Royal Court of Travancore to send, arrived on the scene. Eventually the mob dispersed. On the third night, after the film had opened, her house was set on fire.

However, Rosy, as well as her family, managed to escape. She reportedly ran in the direction of Karamana, and hopped on a lorry that had stopped after hearing her cries for help. The driver was one Kesava Pillai, who was enroute Nagercoil. He took her to his home, and it is said the two of them eventually married. Ironically, Pillai belonged to a Nair household, and after their marriage, Rosy did too. She changed her name to Rajammal – Ammal is used as a suffix by upper-caste women in Kerala and Tamil Nadu to denote respect.

According to the aforementioned article by the Big Indian Picture, years later, Kunnukuzhi reached out to Daniel, who only said he was aware Rosy had managed to escape too, but didn’t say much else. Vigathakumaran ended up being Daniel’s first and only film — he, too, was subject to so much backlash that he had to quit the industry and spent the rest of his days in poverty.

‘The lost child’

Rosy reportedly died in 1988. Most accounts of her story are retellings, because while she was still alive, no one remembered, appreciated, or cared for the great feat she had achieved as a minority woman. The News Minute states that her children, who now live as Nairs, are reluctant to acknowledge her past before she met their father. In a video released by Asianet in 2013, the team tracked down Rosy’s daughter, Padma, in Madurai. “I don’t know how she was before she got married. But afterwards, she wasn’t into [acting],” Padma says. The team also tracked down Rosy’s brother, Govindan, who says her husband was a progressive man who didn’t discriminate against her family for their caste.

Much like Chandrakumar, who was lost and eventually found in Vigathakumaran, P K Rosy was lost for mainstream discussions in cinema and history, and only “found” decades after her passing, when film historians like Kunnukuzhi and author Vinu Abraham brought her story to the limelight. In 2013, a film named Celluloid was released, but was criticised by the Dalit community for not focussing on Rosy’s own struggle.

As film critic G P Ramachandran told The News Minute, “Even if Kerala may have overcome many caste-based discriminatory practices that exist in other states, caste is still very much relevant here. There was an uproar in those times because she played a Nair women, but even after that, there haven’t been too many Dalit women actors.”

Ramachandran goes on to say that there have been actors like Kalabhavan Mani, who was Dalit, but many women actors were reluctant to act with him. Moreover, he wasn’t given too many roles of a main hero. “There have been very few films with Dalit women characters, and even when they are released, the roles are performed by others. Two films that come to mind are Neelakuyil and Kismath,” he said.

While Rosy was, no doubt, a pioneer in Malayalam cinema, the industry failed to recognise her as such till it was much too late. Today, among a host of other problems, Indian cinema lacks an inclusive space, and Dalit representation in the industry remains arguably laughable. Had P K Rosy not been forced to flee her state by the moral brigade, and had been given a chance to bring more of her talent to light, would she be satisfied with the way we treat caste in her beloved industry almost a hundred years later? Perhaps not.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167