Before ‘Saving The Environment’ Was a Catchphrase, The Chipko Movement Showed Us How It’s Done

It's time policymakers remembered that without forests, any potential battle against climate change is a lost cause. #ChipkoMovement

As an apostle for non-violent resistance against environmental destruction, the Chipko Movement continues to resonate with millions around the world.

Today, Google is celebrating the 45th anniversary of this remarkable movement through a special doodle posted on its homepage.

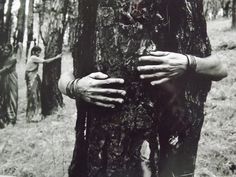

Embracing the Gandhian philosophy of peaceful resistance, this landmark environmental movement of the 1970s derives its name from the manner in which locals from the Alaknanda Valley (modern-day Uttarakhand), primarily women, embraced trees to protect them from being cut by loggers.

Historians, however, have traced this method back to another movement in 18th century Rajasthan, when members of the Bishnoi community resisted an order by the Maharaja of Jodhpur to cut trees by hugging them. Following this, the Maharaja reversed his position and issued a royal decree, banning the felling of trees in all Bishnoi-inhabited villages.

“When Chipko was launched in faraway northern India, and it reverberated in the world that had not invented internet yet, India did not have the Forest Conservation Act (it came in 1980), the Environmental Protection Act was way too long to be legislated (it came in 1986 in the aftermath of Bhopal Gas Tragedy of 1984) and a forest policy had not been formulated (it was framed in 1988). But there were people whose voices were being heard,” writes Abhilash Khandekar in Urban Update. All that changed with the Chipko Movement.

Those voices were of the locals in the Alaknanda Valley led by the Dashauli Swarajya Seva Sangh (DGSS), which began as a labour cooperative but morphed into the “mother organisation” of the Chipko movement, and the thousands that joined later. Women, especially, were on the frontlines of this movement.

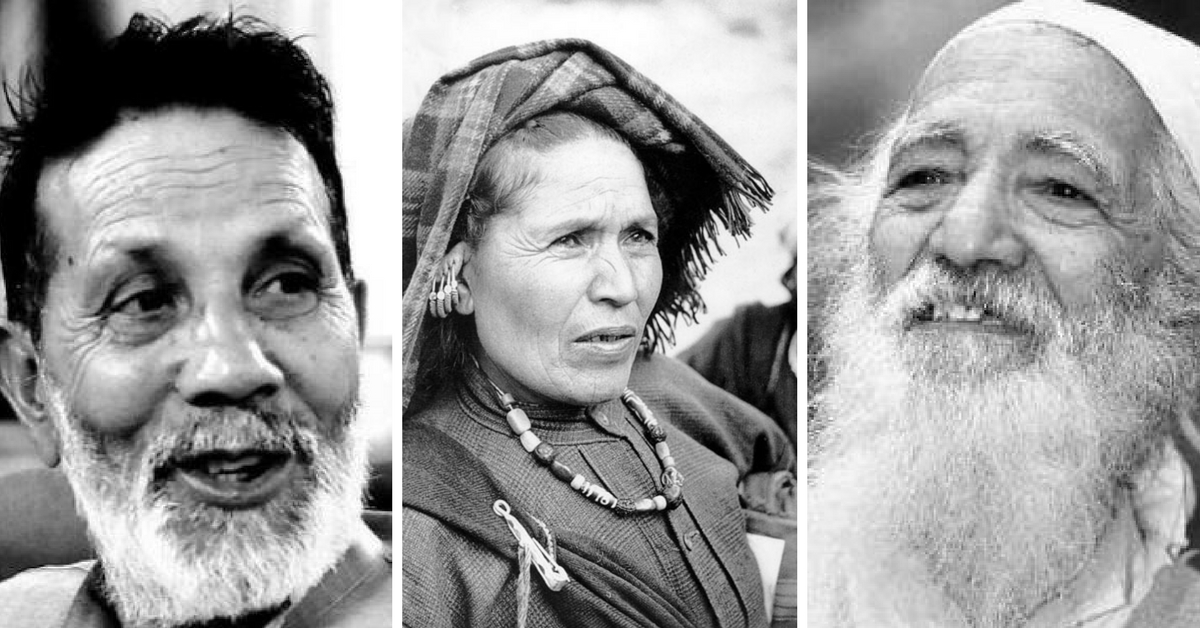

Founded by Chandi Prasad Bhatt, a former transport clerk who came from a family of priests, the DGSS’s (now DGSM, with “Mandal” replacing “Sangh”) sojourn into social activism began in 1964 as a labour cooperative which promoted local cottage industries that generated employment and sought the sustainable utilisation of forest produce.

For nine years, the DGSS entered into occasional tiffs with the State government over rampant commercial logging which not only threatened the livelihoods of local villagers who depended on forest produce but also resulted in major ecological damage.

Matters came to a head in April 1973, when the then Uttar Pradesh government rejected a request for the allocation of seven hornbeam trees to make agricultural tools, but instead, awarded the Simon Company, an Allahabad-based sporting goods manufacturer, a contract to fell 300 trees.

On April 24, 1973, residents from Mandal village situated close to the forest land under dispute, took heed of Bhatt’s call and threatened to physically embrace the trees rather than allow the loggers to cut down their source of sustenance.

Shaken by the standoff, the loggers left the site. Historians of the movement often refer to how the movement was called “anglawaltha,” the local Garhwali word for an embrace, which then soon translated into a more popular Hindi word “Chipko,” i.e. to stick.

Following the success at Mandal village, the movement for access to forest produce grew into one against rampant commercial logging and environment protection, spreading across to other villages in the valley. The movement, however, attained immortality near Reni village on March 25, 1974.

Earlier that year, the government had announced an auction for the felling of 2500 trees near the Reni village, overlooking the Alaknanda River. On hearing the news, Bhatt and his DGSS volunteers gathered local villagers and organised a protest against the government, which among other acts, involved hugging trees. Public meetings, rallies and other such acts of defiance were conducted in the following weeks in Reni village and the adjoining areas.

Read also: Bengaluru Environmentalist Reveals How to Save on Water & Electricity Bills Without Losing Comfort

In a bid to have their way, the State government and local contractors diverted the attention of the DGSS and local men to Chamoli under false pretences of compensation. With the DGSS and local men away from the Reni village, the government and contractors sent loggers on March 25 to the area near Reni village. On seeing these men coming into the area, a local girl rushed to Gaura Devi, the head of a local women’s group, and told her about their arrival.

Leading a group of 27 women to the site, Devi confronted the loggers. When all conversation failed to break the standoff, the loggers began hurling abuses at the women, besides pointing guns at them. However, the 27 women were having none of it and refused to back down. Instead, they hugged the trees to prevent them from being cut down.

This went on all night, and the women displayed remarkable fortitude in guarding the trees until the following morning when the men and DGSS volunteers returned. News of their resistance spread to other nearby villages, with more people joining the movement. After a four-day impasse, the contractors left. The State government soon acquiesced to their demands and issued a 10-year ban on all tree-felling in this area.

“In the Chipko Movement, women became involved through a different process. There was a sustained dialogue between the Chipko workers (originally men) and the victims of the environmental disasters in the hill areas of Garhwal (chiefly women). Women, being solely in charge of cultivation, livestock and children, lost all they had because of recurring floods and landslides (as a result of the rampant felling of trees). The message of the Chipko workers made a direct appeal to them. They were able to perceive the link between their victimisation and the denuding of mountain slopes by commercial interests. Thus, sheer survival made women support the movement,” writes Shobita Jain, a sociologist, for the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

Another major protagonist of the movement was the Gandhian activist and environmentalist Sunderlal Bahuguna, whose personal appeal to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1980 resulted in a Centre-backed ban on felling of trees in the Himalayan region for 15 years until the complete restoration of the green cover.

This was a momentous occasion for the Chipko Movement, serving as a reminder to all and sundry that non-violent resistance can compel the authorities to change their mind. He also coined the famous slogan “Ecology is permanent economy,” besides undertaking a mammoth 5,000 km-long march across the Himalayan region from 1981 to 1983. In these two years, he did spread awareness about the movement, besides enrolling more volunteers in the process.

“Chipko was born in the Alakananda valley; its midwives were Bhatt and his co-workers in the DGSS. Later it moved eastwards, to Kumaun, where the protests against commercial forestry were co-ordinated by left-wing students of the Uttarakhand Sangharsh Vahini; as well as westwards, to the Bhagirathi valley, where the movement was led by Sunderlal Bahuguna and his associates. Within its original home, the movement had entered its second phase: that of reconstruction.

Read also: 9 Powerful Citizen Led Movements In India That Changed The Nation Forever!

Under Bhatt’s leadership, the DGSS organised dozens of tree-plantation and protection programmes, motivating the women (especially) to revegetate the barren hillsides that surrounded them. Within a decade this work had begun to show results. A study by SN Prasad of the Indian Institute of Science showed that the survival rate of saplings in DGSS plantations was more than 70%, whereas the figure for Forest Department plantations lay between 20% and 50%,” writes noted historian Ramachandra Guha for this 2002 column in The Hindu.

The Chipko Movement was the harbinger of many environment-related agitations in both India and around the world. In India, the movement would inspire legislation introduced to save the environment, besides spreading awareness about the value of green cover.

At a time when climate change, reforestation drives and saving the environment are dominating policy discussions, the Chipko Movement continues to inspire. Having said that, the movement has done little to alter government policy despite the introduction of legislation aimed at protecting the environment and sustaining local communities that depend on forest produce.

“Forests in India are shrinking fast, but there is no trace of a Chipko-like Andolan now. Tropical forests are under grave danger, and in the name of development, lakhs and lakhs of trees are being removed to make roads, rail tracks, Metros in cities and factories,” Bahuguna said last year.

Today should remind policymakers that without forests, any potential battle against climate change is a lost cause.

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167