To Ban or Not to Ban: Jallikatu, Its Interesting History and Both Sides of the Debate

Seen as a display of cruelty by animal rights activists, but venerated by others as a symbol of Tamil Nadu's martial tradition, Jallikattu evokes polarised reactions from different sections of society. Here's what you should know about the ancient bull-taming sport and the debate surrounding it.

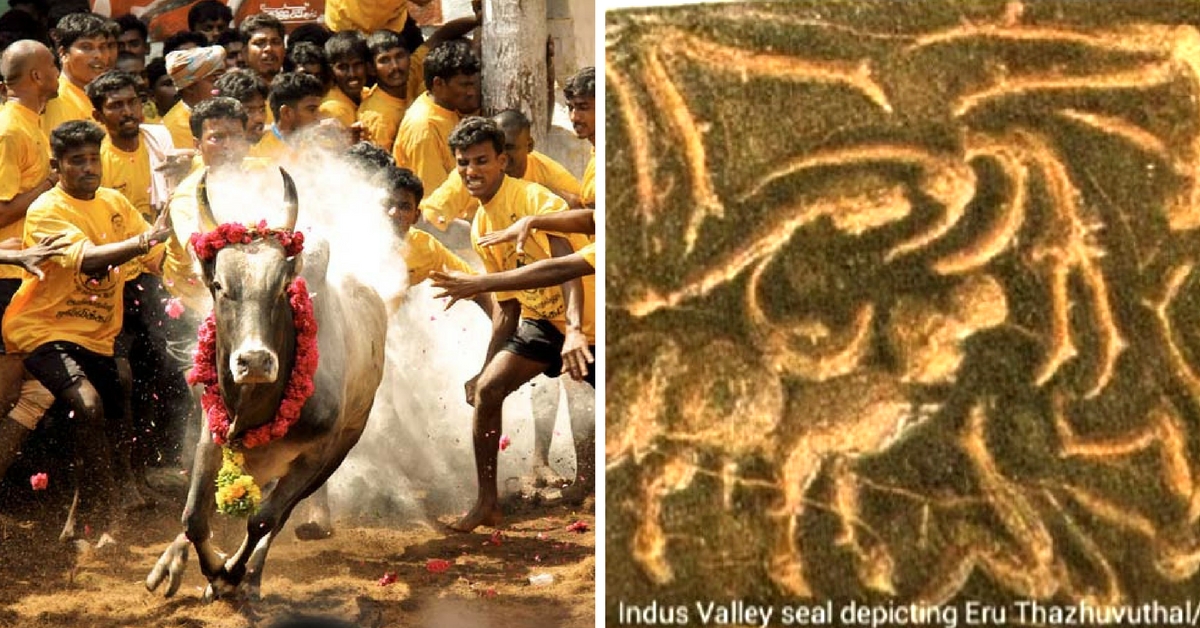

Seen as the baiting of bulls and a ferocious display of cruelty by animal rights activists, but venerated by others as a symbol of martial tradition and Tamil heritage, Jallikattu or Eru Thazhuvuthal (literally, embrace the bull) evokes polarised reactions from different sections of society.

Photo Source

Jallikattu has been practised for thousands of years in Tamil Nadu and finds mention in Sangam literature, which dates back to as early as 200 BC. Historical references indicate that the sport was popular among warriors during the Tamil classical period. The term ‘jallikattu’, comes from Tamil terms ‘salli kaasu‘ (coins) and ‘kattu‘ (a package), referring to the tying of prize money to the horns of a bull. Later, in the colonial period, the name was changed to ‘jallikattu.’

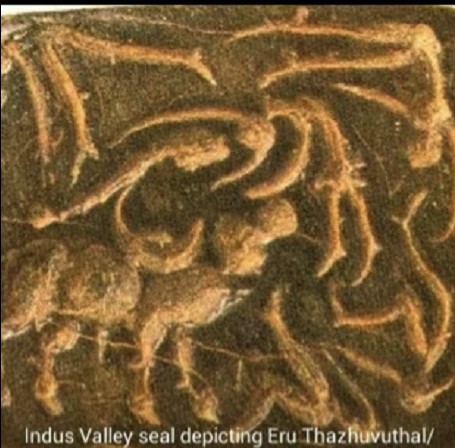

Interestingly, a well-preserved seal found at Mohenjodaro in the 1930s is available at the Delhi Museum, which depicts the bull fighting practice prevalent during the Indus Valley Civilization. Several rock paintings, more than 3,500 years old, at the remote Karikkiyur village in Tamil Nadu also show men chasing bulls with big humps and long, straight horns.

Photo Source

According to local folklore, during the rule of the Nayak kings, an arena – usually the biggest open space in the village – would be designated for the sport to be played. A makeshift entrance, or Vaadi Vaasal, would then be marked out for both competing bulls, which were decorated and garlanded, and for their owners, who would stand in line with them.

Gold coins, wrapped in a piece of cloth, were tied to the horns and the bulls were then released, one by one, onto the field. Excited by the gestures of those who trying to catch him, the bullock would then lower his head and charge wildly into the midst of the crowd, who would nimbly run off on either side to make way for him.

Willing young men would then grapple with the bull in an attempt to untie the knot and get at the prize — they either successfully managed to hang on for dear life, or were simply tossed around like rag dolls, bouncing off the bulls’ muscular body. Winners were greatly admired as the sport required quick reflexes and a fleet foot to tame the recalcitrant bull, which would try to get away, shake off the fighter and, at times, stamp or wound fallen participants.

Photo Source

Traditionally, Jallikattu was played to judge a man’s virility; it was seen as a way to win a woman’s hand in marriage. The men who held on to the bulls, usually reared by the object of their affections, were declared winners. Kalithogai, a classic Tamil poetic work of Sangam literature, speaks of how the bulls were women’s best friends, in that they selected the right partners for them. The text also talks elaborately about how to identify the right kind of bull and train it.

You May Like: 16 Fascinating Facts about Mohenjodaro and Indus Valley, a Civilisation Far Ahead of its Time

Centuries later, the game continues to be about virility, though more that of the bull’s that the man who fights with it. Modern day Jallikattu is played by farming communities in Tamil Nadu to handpick the strongest bulls as studs for their cows so that, in turn, they may sire high-quality calves. Sometimes small farmers are unable to afford to stud bulls, but are free to avail of the common temple bull belonging to the village, called the koyil kaalai.

Photo Source

In most villages in southern districts, bull taming is conducted on the second and third days of Pongal, the harvest festival. The villages of Palamedu and Alanganallur near Madurai have become centres of attraction as tens of thousands of people gather to watch the spectacle of bulls from all over Tamil Nadu, close to 1000 of them, being unleashed in the arena to test the taming skills of fighters. At Alanganallur, one can also see posters put up in remembrance of “fallen heroes” who died fighting the bulls.

A sport that is as fearsome as it is addictive, Jallikattu has become a rallying point for Tamil identity over the years. A ban on Jallikattu by the Supreme Court in 2014 has largely been seen as a negation of Tamil Nadu’s heritage and cultural identity. This month, despite the outrage in Tamil Nadu, the Supreme Court declined to revisit the verdict before the festival of Pongal. As such, several supporters of the sport have been peacefully protesting the decision, with many of them coming together at Marina Beach to get their voices heard.

Photo Source

The Supreme Court, in its judgement banning Jallikattu, goes into great detail about the torture that is meted out to the bulls during play – instances of lemons being squeezed into the bulls’ eyes, chilli powder rubbed on to their genitals, the force-feeding of liquor and even cases of the animal having its tail twisted and bitten – have been brought to light. The country’s apex court also says that there is no merit in the argument that just because the sport has been practised for centuries, it must be allowed to continue. By that token, no unjust or abhorrent social custom could ever be done away with.

On the other hand, the argument made by the protesters is that while it is possible there is a kernel of truth in the allegations made regarding Jallikattu, they have been highly exaggerated and sensationalised to grab media attention. Unlike the matador-style taming of the bulls (which involves deliberate maiming and killing), Jallikattu wasn’t designed to be cruel. The bulls – for the most part, they say – are considered animals of the temple, and are revered and worshiped as such.

Photo Source

Furthermore, Jallikattu supporters argue that as the traditional sport sees native male bulls being raised for the sole purpose of breeding, it works as an effective way to conserve the native breeds of the region. The banning of Jallikattu must then mean that it is only be a matter of time before these native breeds go extinct. (They cite the fact that there were 130 or so cattle breeds in India 100 years ago and now there are only 37.)

At present, outcomes of the debate are still unclear. Whether the protests in Tamil Nadu will result in a revocation of the Supreme Court order remains to be seen. Either way, it is the responsibility of not only the state government but also Tamil people, to ensure that the sport is strictly regulated to prevent any and all kinds of cruelty to the bulls, and to take up the cause of conserving native breeds independent of the Jallikattu tradition.

Here is what two Tamilians have to say about the heated debate surrounding the issue.

Photo Source

Sevugan Somasundaram feels that the ban is not the solution. He says,

“An ancient tradition that goes back thousands of years, Jallikattu should be preserved. I am from the Madurai region and can vouch for the fact that all bulls are not mistreated. Farmers take a lot of effort to rear them and cannot afford to do so. However, it cannot be denied that sporadic instances of cruelty to prize bulls, like giving alcohol or drugs, do happen.

To prevent this from happening, the Supreme Court could have placed stricter regulations on how the sport ought to be played as opposed to an outright ban, which hits at the heart of Tamil Nadu’s cultures and traditions. When there is a doping scandal in any sport, the responsible players are banned, not the sport. I feel that like other sports, there should be a monitoring body which can make and implement rules to enhance the safety of both the animals and men.”

On the other hand, Geetha Subramanian supports the ban. She says,

“There is no denying the fact that Jallikattu has historically always been a part of Tamilian culture but is it really something that we need to be wedded to in the 21st century? No one can argue that this so-called sport is dangerous to the people who participate in it and the spectators and it is also extremely cruel to the animal involved.

There is documented proof of animal abuse wherein the bulls are fed alcohol or their tails are twisted or bitten. And they have no real agency to give consent to be part of this so-called sport. Being a Tamilian means inheriting a culture that is rich, vibrant and beautiful. I really don’t think we need Jallikattu to take pride in its identity.”

Also Read: 7 Landmark Judgements That Were Big Wins for Animal Welfare in India

Like this story? Have something to share? Email: contact@thebetterindia.

NEW! Log into www.gettbi.com to get positive news on Whatsapp.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167