Behind Asia’s 1st Human Dissection: The Doctor Who Brought Modern Medicine to India

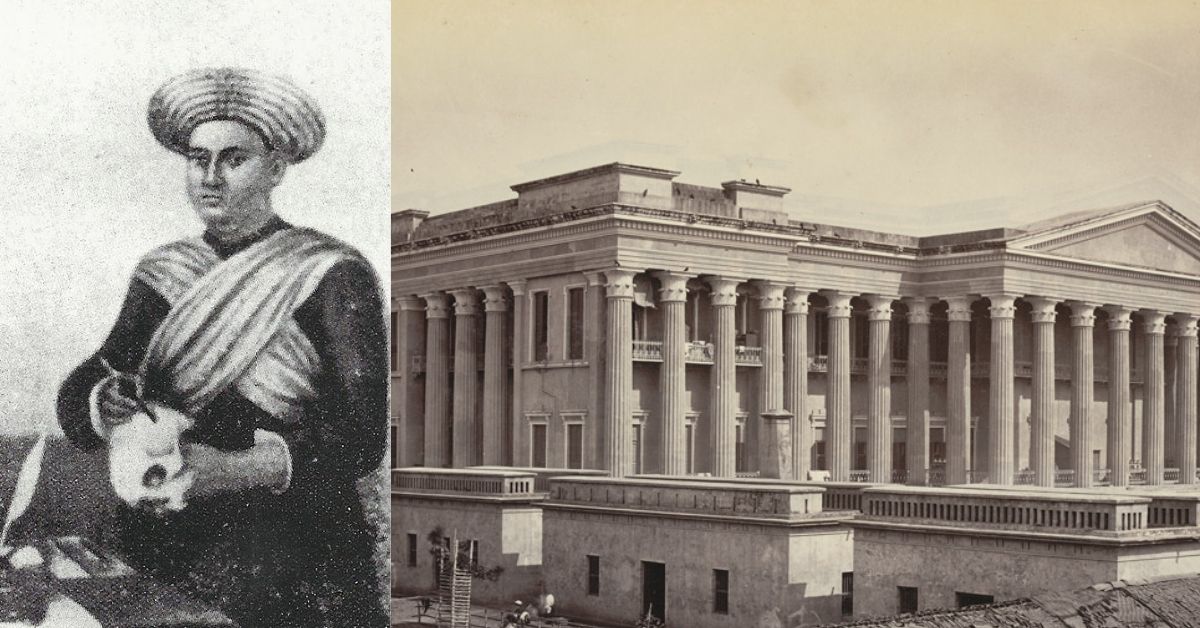

Almost 200 years ago, Kolkata-based Dr Madhusudan Gupta performed India’s first human dissection. But what did it mean for medicine, and how did it affect existing practices in colonial India?

In 2011, doctors from the Calcutta Medical College stumbled upon a few papers regarding the first human dissection performed in India, carried out by Bengali doctor Madhusudan Gupta. This dissection was the first not only in the country, but also in Asia, and was performed around 186 years ago.

Today, this act is widely regarded as the cornerstone of modern medicine in the country.

As Doctor Jayanta Bhattacharya, professor of medicine at Stanford University, wrote in his paper, “The history of Calcutta Medical College is intertwined with the rise of rational scientific medicine in India. This new kind of medicine was premised on dissection-based anatomical knowledge and was secular…The singular act….entailed indelible changes in the perception of body, disease, and self of the Indian population…Arguably, being the first Indian dissector, Madhusudan Gupta is historically tied up with this transformation of medicine.”

But almost two centuries ago, when Dr Gupta made the first cut, the story was entirely different. On a personal level, social ostracisation would follow him for years to come, to the point where his own family kicked him out of their ancestral home. As for the rest of India, it would take some time to come around to history being made right before their eyes.

To understand why Dr Gupta’s actions were deemed outrageous at the time, we must, firstly, understand his background. Then, we must take note of pre-existing barriers to dissection, as well as prevailing notions of ‘purity’.

An ‘unholy’ act for a doctor

Dr Gupta was born into a Vaidya (traditional ayurvedic practitioners) family in Hooghly. His grandfather was the family physician of the Nawab of Hooghly, and his great grandfather was a bakshi (paymaster, or those who collect wages). He began his career as a Sanskrit scholar and Ayurvedic practitioner, and while teaching at the Sanskrit College from 1830 to 1835, he attended several anatomy and medicine lectures given by British doctors.

He also spent much of his time working on translations of English texts to simplify the reading of European science. He translated British doctor Robert Hooper’s Anatomists’ Vedmecum, completed under the title Sariravidya (Science of Things Related to the Body).

Meanwhile, Dr Bhattacharya wrote, the mid-18th century was a key period in Britain, where the medical fraternity had started coming to terms with the importance of studying human anatomy. Regions like France, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Italy were doing far better in this regard. English universities, on the other hand, were still stuck somewhere in old practices and arrangements in medicine. In 1828, the University College of London was established. This was a comparatively secular institution when compared to the likes of Oxford and Cambridge.

Alongside, “a utilitarian approach and the military need to provide trained apothecaries, compounders and dressers in different detachments prompted the earliest official involvement with medical education in India. On 9 May 1822, the government laid down a plan for the instruction of up to 20 young Indians to fill the position of native doctors in the civil and military establishments of the Presidency of Bengal. The outcome was the establishment of the Native Medical Institution (NMI) in Calcutta on 21 June 1822,” Dr Bhattacharya added.

There was also the increasing realisation that “native doctors were indispensably necessary to afford medical aid to the numerous detachments from corps in the extensive dominion of India”.

But towards 1833, the tide in Calcutta began to change. A committee was set up by William Bentinck’s government to report on the status of medical education in Bengal, and if “teaching of indigenous systems should be discontinued”.

The committee found that practical human anatomy had been entirely omitted, which resulted in poor quality of medical students “who would never be able to work at par with English doctors”. As a result, NMI was abolished, and medical lessons at the Sanskrit College, where Dr Gupta had been teaching, were discontinued.

In its place, Bentinck established the Medical College, Calcutta (CMC) in 1835. Dr Gupta was transferred here and began working with a group of around 50 students in the execution of the first entrance examination. Even as the course began, teaching anatomy dissection remained a problem for the college authorities.

For Hindus, touching a dead body was mostly out of the question. So dissecting cadavers to understand human anatomy was more or less a pipe dream. In the evolution of the understanding of human anatomy in India, ancient Indian physician Sushruta, deemed the ‘father of brain surgery’, was a fierce proponent of human dissection. After the establishment of the British rule, professors in Madras would teach human anatomy with paste-board models.

So in 1836, when Dr Gupta performed the first human dissection on a cadaver, all hell certainly broke loose. The Wire wrote, “Outside the hospital, a crowd had gathered to protest this unholy act – a Brahmin touching a dead body – so the administration secured the gates and guarded them.”

Dr Gupta obtained approval for the dissection by gathering support and material from traditional Ayurvedic literature. He had prepared for six months before the procedure, which was carried out in secrecy behind closed college gates. He was assisted by four students — among which was Dwarkanath Gupta, one of the earliest Indian practitioners of western medicine, who pioneered a concoction for patients suffering from Malaria.

Drinkwater Bethune, an English educator, would describe the event 14 years later. “At the appointed hour, scalpel in hand, he followed Dr [Henry] Goodeve into the godown, where the body lay ready. The other students, deeply interested in what was going forward but strangely agitated with mingled feelings of curiosity and alarm, crowded after them, but durst not enter the buildings where this fearful deed was to be perpetrated … they peeped through the jilmils, resolved at least to have ocular proof of its accomplishments. And then Madhusuden’s knife, held with a strong and steady hand, made a long and deep incision in the breast, the lookers-on drew a long gasping breath, like men relieved from the weight of some unbearable suspense.”

‘A new paradigm of knowledge’

It was said that several pundits kept a strict vigil on the college so that corpses couldn’t be brought in for dissection. However, in 2011, when the documents were unearthed at CMC, it was found that the anatomy department and professors worked in tandem to smuggle a body in. It was also revealed that Dwarkanath Tagore, successful entrepreneur and grandfather of Rabindranath Tagore, also helped smuggle the corpse in. Tagore, while a critic of European prejudices, was a strong supporter of Western medicine and the CMC.

R Havelock Charles, a surgeon and professor of Surgical and Descriptive Anatomy, CMC, recalled the event in 1899 and said, “The most interesting feature is that in 1835, the Hindu prejudice against touching dead bodies first gave way, and much credit must be given to the original class of students who had the courage to break through the iron bonds of caste, and engage in the dissection of the human body.”

In 1838, the Society for the Acquisition of General Knowledge was established by a group of young Bengalis, as a result of rising public and medical interest in human anatomy. And by 1848, CMC was seeing close to 500 dissections a year.

Dr Bhattacharya said that the dissection brought forth many changes in perceptions of body, disease, and self. There were also enormous sociological consequences in terms of Indian practitioners adapting to Western medicine and adopting the value-neutral and clinically detached approach of modern medicine. And Calcutta was brought to the same footing as London, wherein CMC became the first college in Asia to be recognised by UCL.

“The study of modern anatomy reconstituted: (a) hitherto existing notion of disease and non-disease; (b) science and reason vis-à-vis tradition and superstition; (c) physicians and non-physicians, and (d) social hierarchy between modern medical practitioners and all other indigenous practitioners. The lived experience of the body became a measurable and repairable phenomenon. The body became a three-dimensional space (unlike the two-dimensional Āyurvedic bodily frame through which dosa-s, dhātu-s and mala-s flow). The role of ‘divine’ was banished forever. Medicine in India was all set for this new paradigm of knowledge and knowing the body,” he added.

Dr Gupta’s medical prowess did not stop at changing the way India studied human anatomy. He also conducted extensive studies on puberty and high neonatal and maternal mortality in Indian women, fought vaccine hesitancy concerning smallpox, and advocated for proper drainage and ventilation to reduce diseases.

In particular, his study of puberty in girls, which was otherwise deemed a ‘private matter’, provided plentiful useful information on menarche among Hindu girls. It dismissed the myths surrounding “discrepancies in menarche between British and Indian women”.

Over time, Dr Gupta developed diabetes and contracted an infection during dissection, which led to gangrene of the hands. He died of septicemia in 1856.

Needless to say, practising medicine without understanding the human body is impossible. And throughout history, India has made many medical contributions to the rest of the world. Through a simple act, Dr Gupta’s name, though mostly missing in the annals of historical records, is deeply intertwined with these achievements.

Sources:

Bhattacharya, Jayanta. (2011). The first dissection controversy: Introduction to anatomical education in Bengal and British India. Current science. 101.

This ‘Untouchable’ Caste is Indispensable to Kolkata Hospitals by Sohini C for The Wire, Published on 18 December 2018

175-year-old dissection papers unearthed by The Times of India, Published on January 13, 2011

How the Calcutta Medical College Led to the Rise of Biomedicine in India by Kiran Kumbhar for The Wire, Published on 28 March 2019

Edited by Yoshita Rao

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167