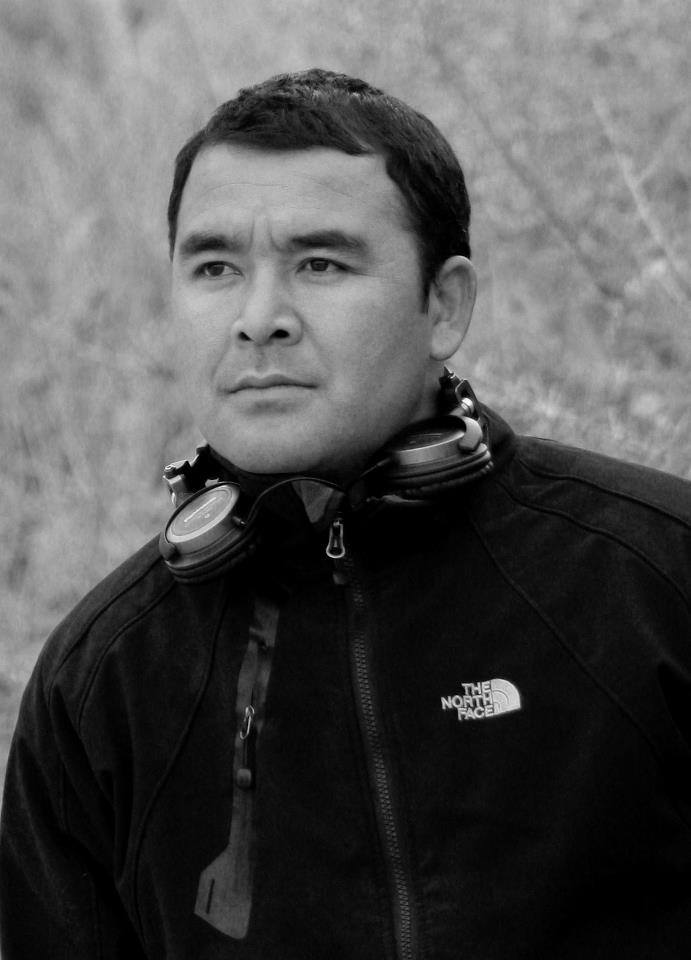

After Losing Mom to Cancer, Ladakh’s ‘Nomadic Doctor’ Helped Save 1000 Women!

Doctor Nordan has even conducted free clinics and distributed medicines in acutely remote villages, in addition to turning Nubra Valley into a tobacco-free zone.

There were two women who changed the course of Dr Nordan Otzer’s life. The first was his mother.

“It was 2007. I was working at a hospital in rural Tamil Nadu when I received news that she had cervical cancer, which had spread to her liver. I rushed home, and within a month, she passed away,” he recalls.

Using the contact-free sensor that’s placed under your mattress, Dozee tracks and analyzes your heart health, respiration, sleep quality, stress levels and more

It was a major turning point in his life because until then he had harboured ambitions of working at a big hospital and settling down abroad.

Instead, he returned home to his village of Hunder in Nubra Valley and took up work at a nearby district government hospital as a medical officer.

“While working at the hospital one day, I received a call from Mr Ishey Tundup, the principal of a school in Leh. He was unable to track down one of his students, Sonam Dolma,” says Dr Nordan (37).

Dr Nordan and his friend eventually tracked her down in Digger village, Nubra. When they went to the house, her parents were working in the field, and she was inside. “Dolma’s right leg had been amputated below the knee, as she had bone cancer. She was in devastating pain, and I couldn’t withstand the feeling of helplessness I felt. We spoke to the parents and talked about getting her treated in Delhi, and assured them that we would find a sponsor,” he recalls.

This was the second major turning point in his life.

Despite the seriousness of her condition, Dr Nordan felt that they could at least help her live without pain. After finding a sponsor, they took her for further treatment in Delhi. Since the cancer had spread, the doctors had to amputate her legs below the hip. She was doing well, pain-free and they even got prosthetic limbs for her.

Sadly, she suddenly died one day.

“After that, I thought enough is enough. People needed to know more about their body and physical health, especially women, with regards to reproductive health. I believed this needed to change,” he says.

Since then, unchained by the structure of a conventional hospital, this ‘nomadic doctor’ has done a remarkable job of spreading the gospel of modern medicine in this remote corner of India.

Early Days

Born and raised in Hunder, which is famous for its sand dunes and Bactrian camel, Dr Norda’s father was a government school teacher and his mother a farmer.

He studied at a school situated in a nearby village called Diskit until Class VI and enrolled into the Sainik School in Nagrota, a town in Jammu district, from Class VII.

“My father was a school teacher, and his salary wasn’t enough to pay for the higher education of his four children, including me. To supplement his income, however, my brothers and I worked with our parents in the fields during the vacations all through the day to grow massive quantities of vegetables that we would supply to the Indian Army,” he recalls.

Inspired by their parents’ work ethic, all four brothers, among whom Dr Nordan was the youngest, worked their tails off. In 2000, he got admission into CMC, Vellore, and graduated with an MBBS six years later.

Raising awareness, screening for cervical cancer

In Nubra, the challenge before Dr Nordan was to generate a conversation around women’s health and shed all the taboos associated with it.

“When I would talk about the cervix or breasts, these women would look down in shyness. However, looking into their eyes, I could sense that they were grateful that someone was talking about these issues and raising awareness amongst them. Through this one-year outreach initiative, I met nearly all the women residing in Nubra. I spoke to them about the symptoms of breast or cervical cancer and the need for regular checkups, screening and treatment,” he adds.

Through his friends, he also established contact with some gynaecologists in Singapore, whom he invited to Ladakh. He sought their help to screen women for cervical cancer because no one was doing it there and treat them.

“Thanks to our initial outreach, when it came to screening, hundreds of women turned up—even those who were healthy and had no symptoms or health issues,” says the doctor.

Started in 2010, under the banner of Himalayan Women’s Health Project, the team of doctors led by Dr Nordan has screened around 10,000 women from across Ladakh in the last nine years. Of them, 1,000 had precancerous lesions.

“There is a very non-invasive, low morbidity, painless and simple procedure to treat these precancerous lesions. It’s called the screen-and-treat approach. Women are treated in a single visit, where they can do the screening and diagnosis as well in one go,” says Dr Quek Swee Chong, a Singapore-based specialist in Obstetrics and Gynecology, who first met Dr Nordan in 2009.

Dr Quek was among the team of doctors from Singapore who helped Dr Nordan in this initiative.

Speaking about his experience, he says that the first few years involved fact-finding, getting a feel of the level of disease prevalence, and establishing trust with the local population.

“Since we were unable to speak the language, we needed someone who had a firm knowledge of local realities, a rapport with the patients and Dr Nordan was that person. He was a translator, facilitator and critically, brought awareness to the concept of screening to the local populace. He went village to village and door to door to persuade the women, encourage them, and ensure that they felt comfortable, safe and secure,” he adds.

These camps happen every year with the latest one happening three weeks ago in Nubra.

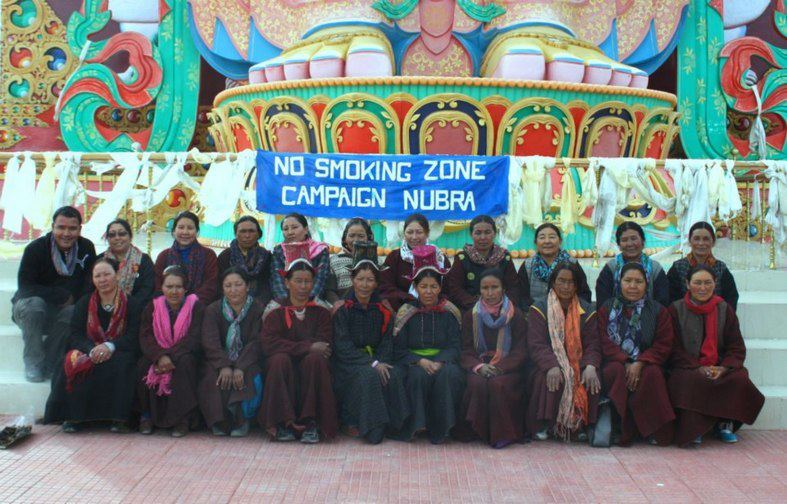

Anti-Tobacco Movement

Another major achievement in Dr Nordan’s kitty is making Nubra a Tobacco-Free Zone. In 2011, there was a growing concern among the local community about the rising incidence of school children from Class VI to VIII smoking cigarettes and developing an addiction.

Working alongside the Women’s Alliance of Ladakh, a voluntary women’s organisation, and other mothers in the region, Dr Nordan helped raise awareness among the local communities about the dangers of tobacco addiction, particularly for young adolescents.

To prevent young school kids from smoking, all shopkeepers in Nubra Valley decided not to transport tobacco products from Leh. Within months, the region was declared a Tobacco-Free Zone.

Dr Nordan, however, is at pains to note that the objective wasn’t a complete ban on tobacco but to make it inaccessible to school kids. Many other villages like Khalste and Durbook have also followed suit.

Healthy Ladakh Movement

Working alongside the women’s wing of the Ladakh Buddhist Association, Dr Nordan and his team visited more than 200 villages in and around Ladakh, specifically Sham, Leh, Changthang and Zanskar region, talking about tobacco and alcohol addiction, besides women’s health-related issues. However, the main focus was on alcohol addiction.

“We weren’t in favour of banning alcohol, but went to various villages and spoke about its health implications. Once people understood the implications, nearly 150 villages decided not to entertain alcohol during wedding processions, or village-level functions,” recalls Dr Nordan.

In the meantime, he began his outreach work in remote corners of Ladakh, which have no access to medical services. There, Dr Nordan and his team would conduct free health check-ups and distribute medicines as well. To pay for these free medicines, he took a bank loan in 2012 to start a restaurant and cafe in Leh.

“Whatever profit I make from these enterprises, it goes into buying medicines, which I distribute for free. Considering my family’s secure financial condition, I don’t have to save any of the money I’m making. I can use that money for social service,” he says.

His family also owns a successful resort called Nubra Organic Retreat, which gives tourists exposure to how traditional organic farming is done in Ladakh.

After more than six years of activism, he went to Kolkata for his higher studies, completing his post-graduation in ENT from the West Bengal University of Health & Sciences, where he was a gold-medallist.

Once again, he returned to Ladakh, but this time as a surgeon, and started working at the Mahabodhi Hospital in Leh.

Meanwhile, he continued his outreach work as well, which he continues to do till this day. Besides, every year, he sponsors a patient with cancer who needs treatment in Delhi.

For 16 months, he even served as executive director of the Ladakh Ecological Development Group (LEDEG), during which time there, they executed various projects and studies addressing urban issues in Leh like groundwater contamination, solid waste management, traffic congestion, air pollution, wastewater management and public spaces.

What continues to motivate Dr Nordan?

“I lost my mother at a young age, and believe that no one else should go through what I did. The solution to our problems is that if people know more about their bodies, they can prevent a majority of the diseases. That is why I do the work I do,” he says.

Also Read: Fresh, Organic & Scrumptious: Why Ladakh is Home to The World’s Sweetest Apricots!

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167