Forgotten Tale: How a Troupe of Artists Healed Assam After the 1960 ‘Language Riots’

To date, this remains the only example in India's history of a purely cultural intervention attempting to broker peace and end violent conflict! #History #Harmony #India

Following the recent National Register of Citizens exercise in Assam, the differences between the Assamese and Bengali-speaking population have come to the fore again.

While it is the prerogative of any sovereign nation to ascertain whether those residing in her territory are there legally or illegally, the NRC exercise in Assam has unfortunately acquired a communal hue thanks to vested political interests.

Although the administration has thus far managed to prevent any large-scale violence, it’s hard to ignore the communal undertones.

However, this wasn’t the case in the summer of 1960, when the state witnessed its first full-scale ‘language riot.’ The riot occurred when Assam passed piece of legislation recognising Assamese as the only official language of the state with a significant Bengali-speaking population.

What ensued was vandalisation, loot and destruction of lives and communities on a mass scale, with the Bengali-speaking population particularly bearing the brunt.

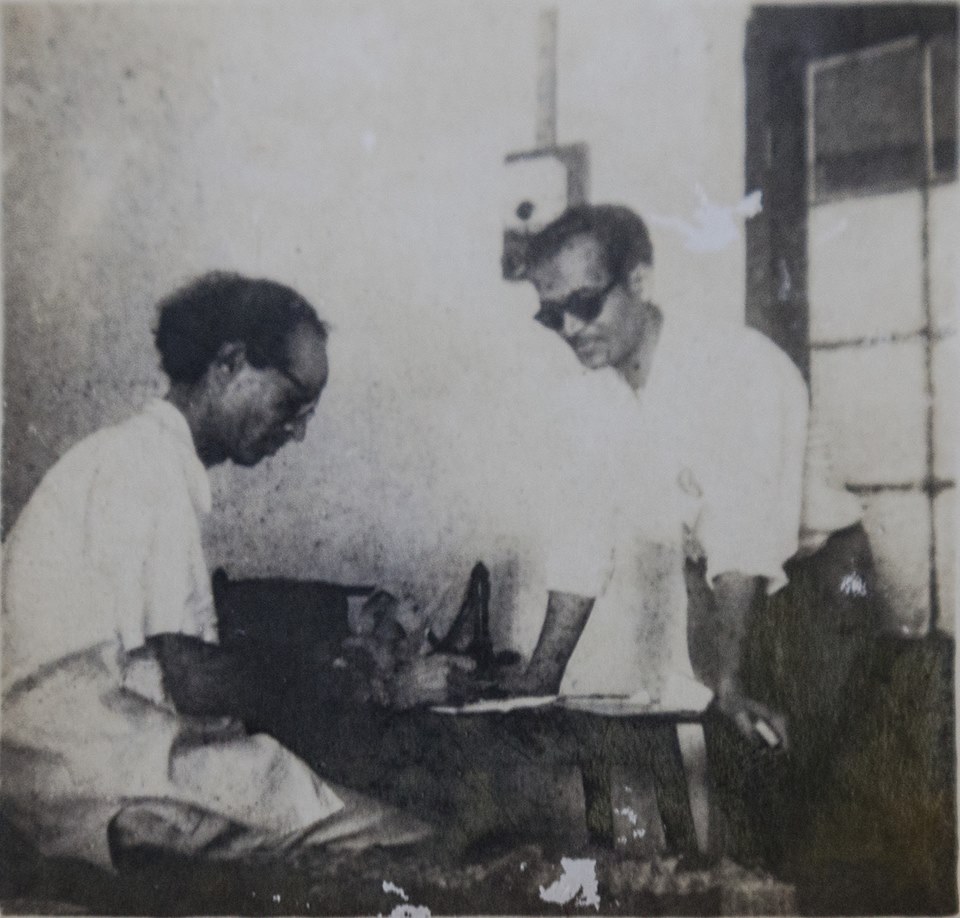

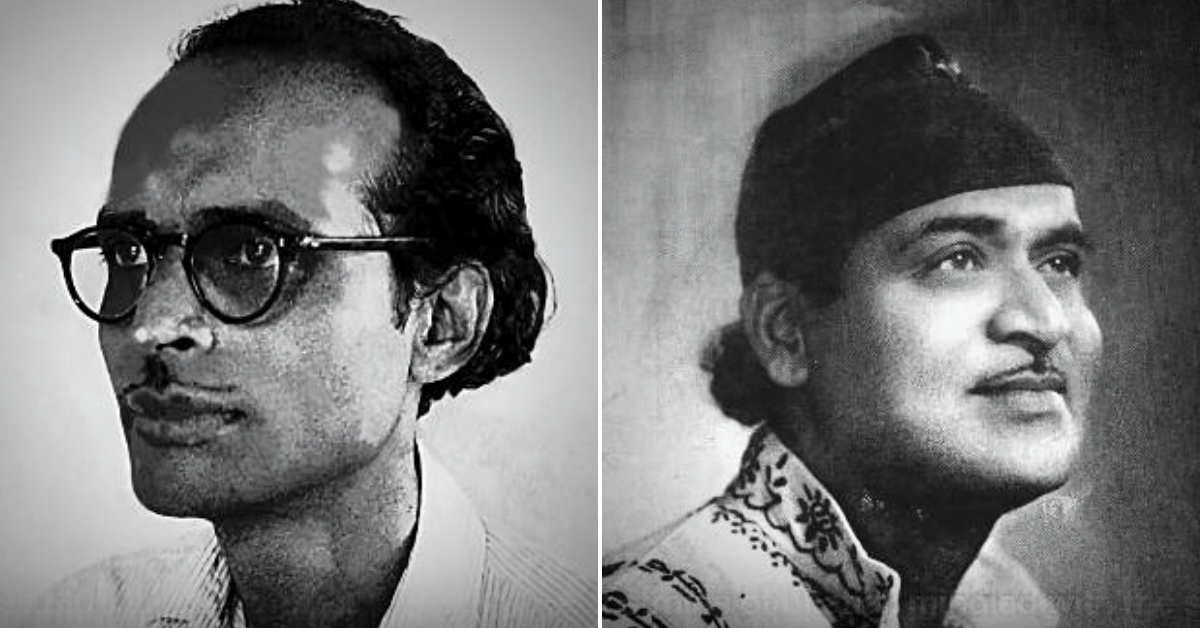

While the politicians couldn’t heal the wounds of the 1960 riots, artists, musicians, dramatists, singers and writers could. Leading this troupe of artists through the riot-torn countryside was Bengali folk singer-songwriter Hemango Biswas and Assam’s very own bard, Bhupen Hazarika.

This was probably the only instance in the history of Independent India, when a cultural intervention healed the wounds of division and brought an end to the widespread unrest.

Today, we know of this intervention thanks to Rongili Biswas, a Kolkata-based economist and folk singer, who has chronicled the efforts led by her father, Hemango Biswas.

Funded by the India Foundation for the Arts and Tata Trust, Rongili began her journey of collecting her father’s writings, photos and recordings, which have resulted in a monograph, film and a song recollecting the journey this troupe of artists made through the riot-torn Assam of 1960.

Earlier this month, Asha Audio, a Kolkata-based recording company, posted a 44-minute clip on YouTube titled ‘Hemango-Bhupen: A Song for Everyone.’ The clip retells this fascinating story through the old photographs and letters that Biswas wrote to his wife Ranu during this journey, allied by six songs sung together by both Assamese and Bengali singers.

On September 9, the Bengali daily Swadhinata commented:

“When in Assam ugly sectarian violence raised its hackles and the country hand its head in shame, when the flood of hatred between Assamese and Bengalis was threatening to ground to dust the respect of a cultured and independent nation, when the two communities were losing their faith in each other, at that time of destruction a clarion call for peace was heard in the hills of Shillong whose creators were the celebrated artistes of the Indian People’s Theatre Association, Hemango Biswas, and the famous singer and film director Bhupen Hazarika.”

According to the writings collected by Rongili, when the riots broke out in Assam, Biswas reached out to Hazarika via telegram, who was in Kolkata at the time. Both artists made their way to the hilly climes of Shillong (the modern-day capital of Meghalaya) and wrote a song titled ‘Haradhan-Rongmon Katha,’ which narrated the story of two peasants—one Assamese and the other Bengali—who had lost their respective homes and heath during the riots.

Setting the tune of this song to both Assamese (Bihu) and Bengali (Bhatiali) folk forms, both artists performed it together at the Shillong Club on August 27, 1960. Much to their surprise, the song struck a real chord with the audience.

“We tried to establish harmony during the Assamese-Bengali conflict. We sang for peace and harmony. We saw, visiting those places where violence and disturbances took place, that people came to listen to our song and speech; the situation got relaxed. Fakhruddin sahib (then President of India) had called us. Bimalla Chaliha (then Chief Minister of Assam) had cried and said ‘…I am defeated, you do whatever you like.’ The violence had gradually increased. Fakhruddin also said shedding tears ‘we will provide everything to you.’ I said ‘on behalf of you, i.e., [the] Government we were not at all willing to sing roaming, you just give us some vehicles. We would later even return the cost of the petrol also. It would be good if you could provide us with just the vehicles, a microphone for spreading the message; and an officer to give company; and give us accommodation,” writes Biswas.

“Thus, instead of going by being the tail of the government we moved on our own way. We started our cultural mission to wipe out the fear of violence and misunderstanding created among people by mistake,” he adds.

Through the journals Biswas left behind, we get an understanding of how some of his comrades had expressed serious doubts about this venture.

“Some comrades started saying why would you go with the help of the Congress government? Besides, it is the good-for-nothing administration of the Congress government that should be held responsible for this riot. How would the artistes from the Indian Peoples Theatre Association (IPTA) cooperate with them?” writes Biswas.

However, there was no way Biswas was going to refuse the call, considering that such an opportunity to heal the wounds between these two communities might have never arisen again. The troupe began their journey in Guwahati city, the commercial centre of Assam.

From there, the troupe made their way to the town of Nagaon, one of the worst riot-affected areas. There, Biswas had expressed some concern for the troupe’s safety. During this leg of the journey, the troupe enlisted Assamese folk singer Khagen Mahanta. Although the Bengali-speaking community did a no-show at the troupe’s gathering, their presence there was nothing short of magical.

“I clearly remember, after the program, three students came to me and confessed with much remorse that they participated in the riots. One of them was a lead worker of student federation,” Biswas writes. The troupe did eventually go onto meet a few leaders of the Bengali-speaking community, but they couldn’t do enough to assuage their fears.

“When they were journeying, the big rioting was over. But what remained was bitterness and a lack of faith. That is when their voices and music worked like magic,” says Rongili, in a conversation with The Indian Express, earlier this month.

Next stop for the troupe was Dhing Bazar, near the town of Nagaon. Arriving there, Biswas writes about how he could “feel the latent tension still prevailing there.” The market was in a state of total ruin. Shops, a Bengali school, an establishment that once sold music records and another costume making enterprise for Assamese rural theatre Bhaona, were all gutted down because of the riots.

Residents of nearby villages gave assurances that no trouble would befall the troupe, and there they performed songs from the Assamese Borgeet and the now globally famous Rabindra Sangeet traditions. They closed their performance there with a rendition of ‘Haradhon-Rongmon Katha’, and by the end of the performance the atmosphere of fear was “crushed” entirely, says Biswas.

Following Dhing Bazaar, the troupe went on to perform at a famous Bengali theatre hall in Jorhat, where the audience comprised Bengalis and Assamese sitting side by side. At the time, no one thought they would see members of these communities sitting alongside one another watching a musical performance. During this performance, Biswas enlisted a famous Assamese dhol player Moghai Ojha of the IPTA, who composed and sang a song.

A translation of those lyrics read like this:

The country is weeping

And its people cry

You are powerful because those people have given you that power.

Why do you people forget this?

Or the intensely satirical one:

Brothers fight among themselves

The enemy is rejuvenated

When husband and wife fight

Home becomes exile. (Source: The Wire/Rongili Biswas)

Despite the cultural form this intervention took, the artists on the troupe weren’t shy about expressing the political realities of the time.

Before the start of their scheduled programme in Tezpur, Kalaguru Bishnu Rabha, a young poet and apparent revolutionary, spoke freely about the prevailing socio-political climate of the time despite hesitation from other members of the troupe. Fortunately, the speech spoke to the people, and in the words of Biswas “Bishnu Rabha had that right.”

Going through Biswas’ writings that have been published by multiple publications, one does get a unique sense of how these respected artists, who spoke in the language of the ordinary Bengali and Assamese speaking person, managed to heal the divisions and suspicions between these communities, if only for a short period of time.

Yes, art does not and cannot solve political problems, but artists can try and for a brief moment, succeed in bridging the divide.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167