Mizo Peace Accord: The Intriguing Story Behind India’s Most Enduring Peace Initiative!

Twenty years before the Mizo Peace Accord was signed, the Indian government under Indira Gandhi had deployed fighter jets to drop bombs on Aizawl!

Mizoram is a model Indian state with a literacy rate only second to Kerala and GDP per capita twice that of Uttar Pradesh. It is the model of stability in a region rife with civil unrest and insurgency.

Why is the state different from her fellow sisters in the Northeast? Most would point to the Mizo Peace Accord signed on June 30, 1986, by Mizo National Front (MNF) leader, Laldenga, Mizoram Chief Secretary Lalkhama, and Home Secretary RD Pradhan. It remains one of Independent India’s few enduring successes at establishing peace following an outbreak of domestic insurgency.

However, the years leading up to the peace accord presented a side of the Indian state that would put any patriot to shame. It was the Indian state at its most brutal, unforgiving and violent. Little wonder that this story is often hidden from public discourse surrounding the Northeast.

The story begins in 1959 when the people inhabiting the Lushai Hills woke up to Mautam (bamboo death).

“Bamboo flowering and the subsequent invasion by rats on granaries and paddy fields in the region is a phenomenon that signals an impending catastrophe or a famine,” former Mizoram Agriculture Minister H Rammawi told the Hindustan Times in 2008.

Unique to the Northeastern states of Mizoram and Manipur, Mautam is a cyclic ecological phenomenon that occurs every 48 years. Records show that the Lushai Hills (aka Mizo Hills) were struck by Mautam in both 1862 and 1911. However, this famine would have grave political repercussions and an outpouring of extreme violence from both sides, especially New Delhi.

When the Mizo District Council (Mizoram was then under the administrative control of Assam) pleaded with the Assam government for a paltry sum of Rs 150,000 to stave off the effects or even prevent the impending famine, the request fell on deaf ears. Ignorant officials in the State government dismissed Mautam as some sort of bizarre tribal superstition.

“As Mautam continued to wreak havoc, thousands died or starved, their crops and livelihood ravaged by rats whose population rose to such alarming levels (running into millions) the state had to run a scheme that rewarded citizens for turning in dead ones—40 paisa for each dead rat. The Loshai Hill People feared the worst,” writes Anand Ranganathan, a journalist who has documented the Mizo insurgency, for Newslaundry. He even wrote a work of fiction titled For Love and Honour that has as its backdrop the 1966 Aizawl bombing.

Instead of coming to their aid, the Assamese administration stamped all over them—declaring Assamese as the official state language, whose knowledge was compulsory for government jobs. Not only were they denied any real assistance during the famine, but also suffered further indignity in having their distinct cultural identity stomped upon, allied with exclusion from the mainstream.

A revolt was on the cards, and it was led by Mizo leader Laldenga, a former havildar in the Army and accounts clerk in the Assam government. Angered by the treatment meted out to his people, he quit his government job and founded the Mizo National Famine Front to protest the famine.

On October 28, 1961, Laldenga established the Mizo National Front (MNF) and asserted the Mizo people’s right to self-determination. Initially, the MNF adopted non-violence to meet its political objective, but the brutal circumstances of the time compelled them to take up arms and establish the Mizo National Army (MNA).

Receiving arms, funding and training from China and Pakistan, the MNF launched a full-scale insurgency. The Indian government’s response was to launch a devastating operation against the MNA, driving its members across the border into East Pakistan. Finally, in 1963 Laldenga was arrested and brought to a court in Assam on charges of treason. Strangely enough, he was acquitted.

“On February 28, 1966, the bottled-up anger—against Assam, against India, against perceived and real injustices; against geographical claustrophobia—found its release, in the form of Operation Jericho. At 22:30 hours, a gang nearing a thousand MNF men took control of the BSF and the Assam Rifles Camp. Soon after, they damaged the Telephone Exchange—leading to a complete disruption of government communication—before taking over the Treasury and other important government buildings in the region,” writes Anand Ranganathan for Newslaundry.

On the following morning, the MNF released a 12-point declaration stating the desire of the Mizo people for independence from the Indian Union. After three days of relative calm, however, came the brutal response of the Indian state, which not many in the mainland know about.

On March 5, the Indian government ordered the deployment of four fighter jets, which bombed the living daylights out of Aizawl.

Yes, the government saw it fit to bomb unarmed civilians.

Even though the death toll was limited to 13, what it did was strike fear and further resentment against the Indian government. As one eyewitness account recalls, “There were two types of planes which flew over Aizawl—good planes and angry planes. The good planes were those which flew comparatively slowly and did not spit out fire or smoke; the angry planes were those which escaped to a distance before the sound of their coming could be heard and who spat out smoke and fire.”

Bombing operations continued till March 13. Making matters worse, the Indira Gandhi government initially stated that it had deployed fighter jets not to drop bombs, but men and supplies. However, the details of this bombing campaign only came out decades later when several writers and former insurgents gave their account of what transpired in those days.

In fact, former chief of the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) B Raman later testified that the air strikes only drew more people towards joining the insurgency, while former Chief Minister Zoramthanga said he had “joined the MNF party and participated in the rebellion due to the relentless bombing of Aizawl in 1966.”

Therefore, there is no disputing that the Aizawl bombing happened.

“Assam Rifles were still holding out, but the Mizos were all around. We had to bring the Air Force. It strafed them, and it was only after that we were able to push in and get into Aizawl—the situation was very volatile. Heliborne reinforcements were attempted, but the sniping was too close to the camp and too heavy for choppers to come down. Therefore, at last at 1130 hours came the air strikes, IAF fighters strafing hostile positions all around the Battalion area. The strafing was repeated in the afternoon, and it soon became apparent that the hostiles were beginning to scatter. At the end of air action, the Aizawl town caught fire,” said Mathew Thomas, commanding officer of 2 PARA.

Following the air strikes, the Indian armed forces undertook a swift and ruthless operation, securing all the major borders and preventing any sort of supplies coming in from Burma and East Pakistan. In a matter of days, the MNF rebels were left scattered on either side of the border and curfew was imposed in the region.

Laldenga, meanwhile, escaped into exile in Bangladesh until the defeat of Pakistani forces in the 1971 war. He subsequently moved to Pakistan and eventually London.

Since the insurgency had support from the people, the Government of India came up with yet another drastic plan to offset it. Envisioned by Lt General Sam Manekshaw, the strategy saw the government uproot nearly 80% of the population and resettle them in heavily guarded “fenced-in protected villages or regrouping centres,” writes journalist Sushant Singh for The Indian Express.

Given a week’s notice, locals were forced out of their villages, which were subsequently burned down to the ground along with all the food grain they stocked. The aim was to ensure that the rebels did not have the necessary resources to sustain themselves. At these new fenced-in villages, locals were issued ID numbers, and were compelled to attend a roll call at the start and end of the day.

There is a word for this in the English language—ghettoization. The following 15 years saw an uneasy calm between locals and the armed forces stationed there marked by regular street protests, while the local economy fell apart.

Also Read: Here’s Why Northeast Voters Turn up in Greater Numbers Than Rest of India!

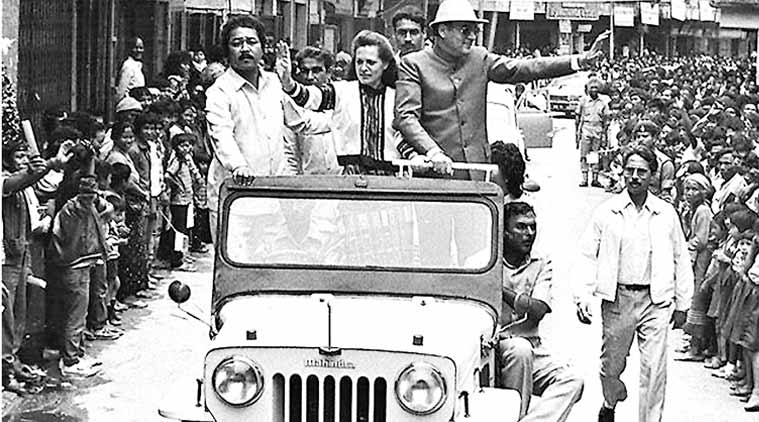

Behind the scenes, however, Laldenga was seeking a way back into India. In the early ‘80s with his family based in London, Laldenga reached out to Indian intelligence personnel stationed in Europe for talks. Former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, however, placed two conditions from Laldenga—cessation of armed violence and a settlement along the contours of the Indian Constitution.

Ironically, the same prime minister that had ordered the bombing of Aizawl in 1966 was talking of a settlement within the contours of the Indian Constitution. With negotiations led on the Indian side by then Home Secretary G Parthasarathy, Laldenga was scheduled to meet Indira Gandhi on October 31, 1984. Tragically, that was the same day when she was assassinated by her own bodyguards.

With Rajiv Gandhi taking over from his mother after a major landslide electoral victory, there was a change in guard with Parthasarathy being replaced by RD Pradhan in September 1985.

In the following month, news came of 750 MNF rebels giving up their weapons and undergoing rehabilitation at a centre in Luangmual on the outskirts of Aizawl, allowing them back into the mainstream. Finally, on June 30, 1986, the day RD Pradhan was to retire from service, the MNF and the Government of India signed the famous Mizoram Peace Accord.

Taking cognisance of the mistakes made in the past, the Government of India agreed to among other things—full statehood to Mizoram, constitutional protection for the Mizo customary law, religion and social practices, recognition of Mizo as an official Indian language and ownership of land. The MNF, meanwhile, agreed to cease all contact with other insurgent groups in the Northeast.

Mizoram was granted full statehood in February 1987. The deal also saw Laldenga becoming interim Chief Minister of Mizoram. Nearly a year later in 1987, he contested the state’s first Assembly election and won. However, defections from his party resulted in his government falling apart in 1988. He died two years later of lung cancer.

However, the enduring legacy of the Mizo Peace Accord remains alive. Among all the peace accords the Rajiv Gandhi government signed—Punjab, Assam, Sri Lanka—it’s the Mizo Peace Accord that has stood the test of time. Meanwhile, the State has since gone on from strength to strength.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167