The Fascinating History of the Fabric That Became a Symbol of India’s Freedom Struggle

Few countries have used fabric as a tool to achieve freedom. And that’s the reason why nearly seven decades after India gained its hard-won independence, khadi continues to inspire and amaze people around the globe.

Few countries have used fabric as a tool to achieve freedom. And that’s the reason why nearly seven decades after India gained its hard-won independence, khadi continues to inspire and amaze people around the globe.

A fabric that embodies a worldview of the past as well as of the future, khadi is a symbol of Indian textile heritage.

The word itself is derived from ‘khaddar’, a term for handspun fabric in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. While khadi is usually manufactured from cotton, contrary to popular belief, it is also made from silk and woolen yarn (called khadi silk and khadi wool respectively).

History yields some very interesting facts about khadi. Hand-spinning and hand-weaving have been known to Indians for thousands of years. Archaeological evidence, such as terracotta spindles (for spinning), bone tools (for weaving) and figurines wearing woven fabrics, indicate that Indus Valley Civilisation had a well-developed and flourishing tradition of textiles.

In fact, the famous stone sculpture found in Mohenjodaro (dubbed the Priest King by archaeologists) wears an elegant robe with decorative motifs and patterns that are still in use in modern Gujarat, Rajasthan and Sindh. However there is little information available about the actual mode of cultivation or method of spinning used by the Harappans.

The earliest descriptions of cotton textiles in India comes from ancient literary references. In 400 BC, Greek historian Herodotus wrote that in India, there were “trees growing wild, which produce a kind of wool better than sheep’s wool in beauty and quality. The Indians use this tree wool to make their clothes.”

When Alexander the Great invaded India, his soldiers took to wearing cotton clothes that were far more comfortable in the heat than their traditional woolens. Nearchus, Alexander’s admiral, recorded that “the cloth worn by Indians is made by cotton grown on trees”, while another Greek historian, Strabo, described the vividness of Indian fabrics.

Interestingly, a few 5th century paintings in the Ajanta Caves in Maharashtra depict the process of separating cotton fibers from seeds (called ginning) as well as women spinning cotton yarn!

Another literary evidence is provided by Chanakya’s Arthashastra, compiled during the Mauryan reign in 3rd century BC, which refers to “superintendents of yarn (sutradhyaksha)” who should “get yarn spun out of wool, bark-fibres, cotton, hemp and flax” and “cause work to be carried out by artisans producing goods”.

The trade routes established by Alexander and his successors introduced cotton to remote parts of Asia and eventually to Europe. By medieval era, hand-woven Indian muslin was in great demand across the world for its fine translucent quality – every yarn of muslin has a thickness that is 1/10th of a strand of hair.

A woman clad in fine Bengali muslin, 18th-century

There is an interesting anecdote about muslin in the Mughal court. Princess Zeb-un-Nisa, Aurangzeb’s daughter, was once admonished by her father for wearing a transparent dress. Much to the astonishment of the Mughal Emperor, she replied that she was wearing seven layers of muslin!

The advent of the Portuguese in Calicut introduced the linen-like calico fabric (named after Calicut or present-day Kozhikode) and chintz (wood-block printed calicos) to Europe. Initially used as bed covers and draperies, these hand-woven fabrics soon became popular with common people due to their comfort, durability and low costs.

By late 17th century, India’s hand-woven muslin, calico and chintz held sway across markets in Europe.

18th century block printed Indian calico with a chintz pattern

Worried about the threat to their local mills, France and England enacted laws to ban import of chintz in 1686 and 1720 respectively. Next, they flooded Indian markets with low-cost fabrics manufactured in European mills.

This, along with introduction of textile mills in Bombay, resulted in a sharp dip in the production of handwoven khadi in India. Millions of weavers across India lost their livelihood as machine-made textiles from Manchester took over the market.

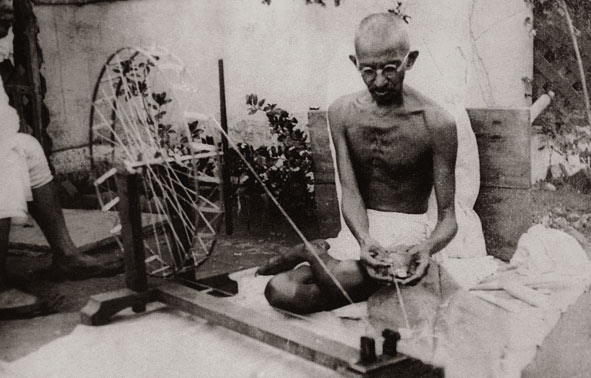

The decline continued till it was single-handedly halted by a diminutive, bespectacled man who wanted to make the charkha (spinning wheel) the basis of India’s economic regeneration: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Gandhi didn’t just revive India’s flagging Khadi industry, he made the humble hand-spun fabric the symbol of all things swadeshi. When he encouraged people across India to boycott British-made clothes, spin their own yarn and wear khadi, he was encouraging them to rediscover their pride in their heritage while lending their support to their rural brethren.

This understated masterstroke took the freedom movement beyond the rarefied circles of the educated social elite and out to the masses. This was also Gandhi’s way of highlighting Britain’s exploitative policies and making a huge symbolic dent on the legitimacy of the British colonial rule in India.

“If we have the ‘khadi spirit’ in us, we would surround ourselves with simplicity in every walk of life. The ‘khadi spirit’ means infinite patience. For those who know anything about the production of khadi know how patiently the spinners and the weavers have to toil at their trade, and even so must we have patience while we are spinning the thread of Swaraj”, Gandhi says in a famous quote.

The picture of Gandhi at his charkha, is therefore, not just a historic photograph: it represents the true spirit of India’s decades-long freedom struggle.

In 1925, in the aftermath of the Non-Cooperation Movement, All India Spinners Association was established with the aim of propagating, producing and selling khadi. For next two decades, the organisation worked tirelessly to improve khadi production techniques and provide employment to India’s impoverished weavers.

You May Like: How Supporting India’s Handcrafted Products Can Also Help Protect the Environment

After Independence, the Indian government established the All India Khadi and Village Industries Board which later became the Khadi, Village and Industries Commission (KVIC) in 1957. Ever since, KVIC has been planning and executing the development of khadi industry in India. It works towards promoting research in production techniques, supplying raw material and tools to producers, quality control and marketing of khadi products.

By the early 90s, khadi had started becoming a fashion statement. In 1989, KVIC had organised the first khadi fashion show in Bombay, where over 80 styles of khadi wear were showcased. In 1990, the brilliant designer-entrepreneur Ritu Beri presented her first khadi collection at the prestigious Tree of Life show held at Delhi’s craft museum, catapulting the fabric into the big league. Now an advisor to KVIC, Beri is working to take khadi to the global arena.

As India stepped into the 21st century, a new breed of Indian designers began experimenting with this versatile fabric, ensuring that khadi remained in vogue.

While the eco-friendly fabric was already known for its rugged texture, comfortable feel and ability to keep people warm in winter as well as cool in summer, its new-age reinterpretation as a modern yet quintessentially Indian textile has made it very appealing to millennial generation.

From dresses and jackets to bridal lehengas and deconstructed local silhouettes, several leading designers (like Sabyasachi, Wendell Rodricks and Rajesh Pratap Singh) have taken on the fashion challenge to reinvent the humble fabric into high-fashion wear.

For instance, Kolkata-based designer Debarun Mukherjee feels that fashion needs to go hand-in-hand with sustainability and has thus made khadi the leitmotif of his bridal line (called Khadi Resplendent).

“Khadi has always been associated with the old; I wanted to change this mindset. I wanted to promote khadi for power dressing. If styled well, khadi (be it cotton or silk) could work for any occasion.

My clothing line fits anyone who is not just looking for pretty clothes but a soul or a story in what they wear, a strong Indian identity, aesthetics and a conscience. The colour and textures of khadi are such that it becomes an inspirational fabric. It is not decorative but a fabric which breathes.

Also, khadi is the most natural, organic fabric. Ideal for Indian weather conditions, it keeps the wearer cool in summers and warm in winters,” he says in an interview to the Daily Pioneer.

While new-age khadi products in India are not what you would really call cheap (eg. dyed raw khadi silk fabric is priced at more than ₹ 800 a metre), it is not exclusive either. At KVIC stores, one can purchase a small charkha for ₹ 550 while a bundle of raw, unprocessed cotton costs ₹ 40. In short, it gives people the choice of making their own hand-spun yarn at home.

A part of the warp and weft of India, khadi continues to be special in many ways. As the world moves towards industrial fashion, this fabric of freedom continues to spin incomes for the rural poor while reminding the country of its legacy of sustainable living and self-reliance.

Also Read: The Little Known Story of Himachal Pradesh’s Unique Handkerchiefs That Were Embroidered by Queens

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167