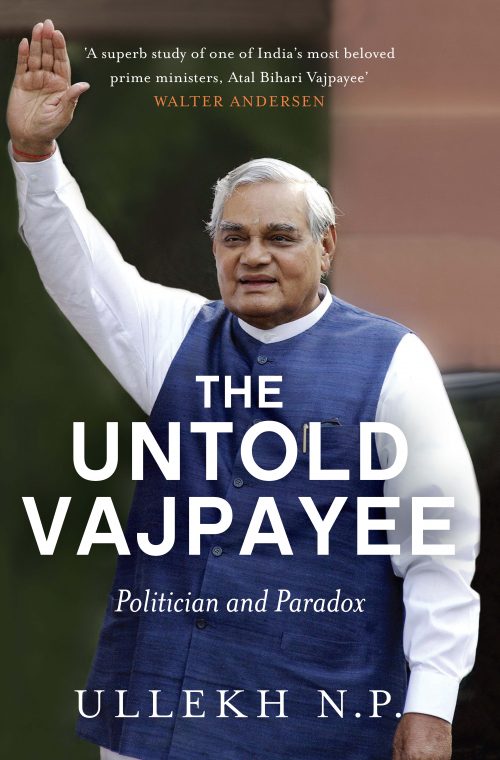

TBI Blogs: BOOK EXCERPT – Was Atal Bihari Vajpayee the Leader Everyone Thought He Was?

Vajpayee, one of the shrewdest politicians of India, is known for negotiating multiple paradoxes—from militant nationalism to his secret family life, his stint as a communist, his indulgence in food, and his attempt to project himself as a moderate, if not a liberal.

Vajpayee, one of the shrewdest politicians of India, is known for negotiating multiple paradoxes—from militant nationalism to his secret family life, his stint as a communist, his indulgence in food, and his attempt to project himself as a moderate, if not a liberal.

On the wintry 31 December evening of 1976, when Ram Bahadur Rai, then the general Secretary of the ABVP, called on Vajpayee at the latter’s 1 Feroze Shah Road residence, he was treated to a warm cup of tea. Rai had paid the visit in haste and concern because he had heard some news: Om Mehta, minister of state for home, personnel and parliamentary affairs in Indira Gandhi’s government, had met Vajpayee. He knew nothing else, and wanted to confirm the news.

“Is it true, Vajpayeeji, that Om Mehta came to meet you?” Rai asked.

Pat came the reply: ‘No. He is a big shot. He didn’t come to meet me. I went to meet him.’

Rai, now the president of the board of trustees of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts, was stunned. He couldn’t believe that his leader had gone to meet a Congress minister who was considered far more powerful than even the Union Home Minister, Brahmananda Reddy, all thanks to his great rapport with Mrs Gandhi.

The young ABVP leader was silent for a while, and then asked Vajpayee about the outcome of the meeting with Mehta.

![By Ricardo Stuckert/PR [CC BY 3.0 br or CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://en-media.thebetterindia.com/uploads/2017/01/Atal_Bihari_Vajpayee_cropped-500x655.jpg)

Suppressing his fury, Rai denied that it was ABVP workers who unleashed violence. “That is untrue and there is no question of us apologising even if we have to go to jail,” Rai replied emphatically.

Vajpayee took umbrage and whispered that it was easy for people like Rai to make such bold statements while older people like him preferred a democratic set-up. “We also want elections and democracy,” Rai submitted. The meeting was over.

The ABVP did not apologize. It took another year for the Emergency to be called off.

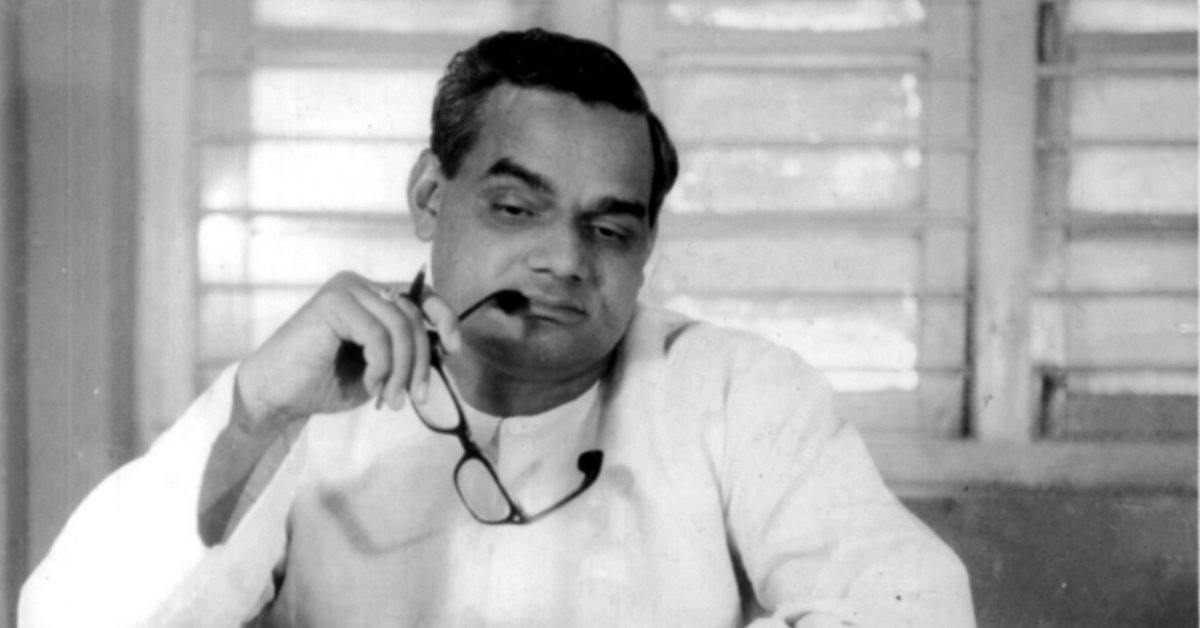

That day, Rai, who later become the editor of Jansatta, realized that Vajpayee had a public persona very different from his real one. It dawned on him how easily Vajpayee adapted to new political realities, and how ambitious he was as a politician.

He may have been a liberal leader, but he didn’t factor in ideology much in his decisions, Rai concluded.

There are those within the Sangh who feel that Deoras’s approach to Mrs. Gandhi during the twenty-two months of the Emergency had a lot to do with Vajpayee’s own position—to lie low rather than fight at a time of major crisis. Interestingly, this was in line with the RSS position even earlier, whenever it faced a ban. It is an altogether different matter that many sevaks suffered under the Emergency, but the leadership, especially Vajpayee and Deoras, kept the channels of communication with the government open, and was ready to yield to any compromise package (such as the one he told Rai about) to kick-start a return to democracy.

No wonder well-known journalist Prabhash Joshi, who had keenly watched the developments during the Emergency, once wrote, “You can decipher a line of action, a pattern [by the RSS whenever it is in trouble]. Even during Emergency, many among the RSS and Jana Sangh [leaders] who came out of the jails gave mafinamas [apologies]. They were the first to apologise. So why is the BJP trying to appropriate that memory?”

At the same time, a section of Sangh insiders looked down upon Vajpayee as a laid-back, fun-loving yet ambitious leader who didn’t worry much about organizational matters or about ideology, which demanded anti-Congressism and aggressive Hindutva posturing. For these insiders, he was merely an orator who wrestled his way up the organization because of his popularity outside. They would also accuse him of plotting to denigrate his opponents within the Sangh. The likes of Rai recall that he used to dictate stories and op-eds to editors of the Organiser and Panchjanya to create bad opinion about his party rivals. Crushing his rivals came easy for him. So did maintaining the public persona of a moderate, a sheep among wolves. But it was precisely this image that the RSS repeatedly referred to as his ‘utility’.

And this celebrated ‘utility’ was on display for all to see at public meetings and poll campaigns.

Read more in The Untold Vajpayee: Politician and Paradox. You can buy the book here.

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167