How a Magsaysay Awardee Doctor Reunited 7000 Mentally-Ill Patients With Their Families

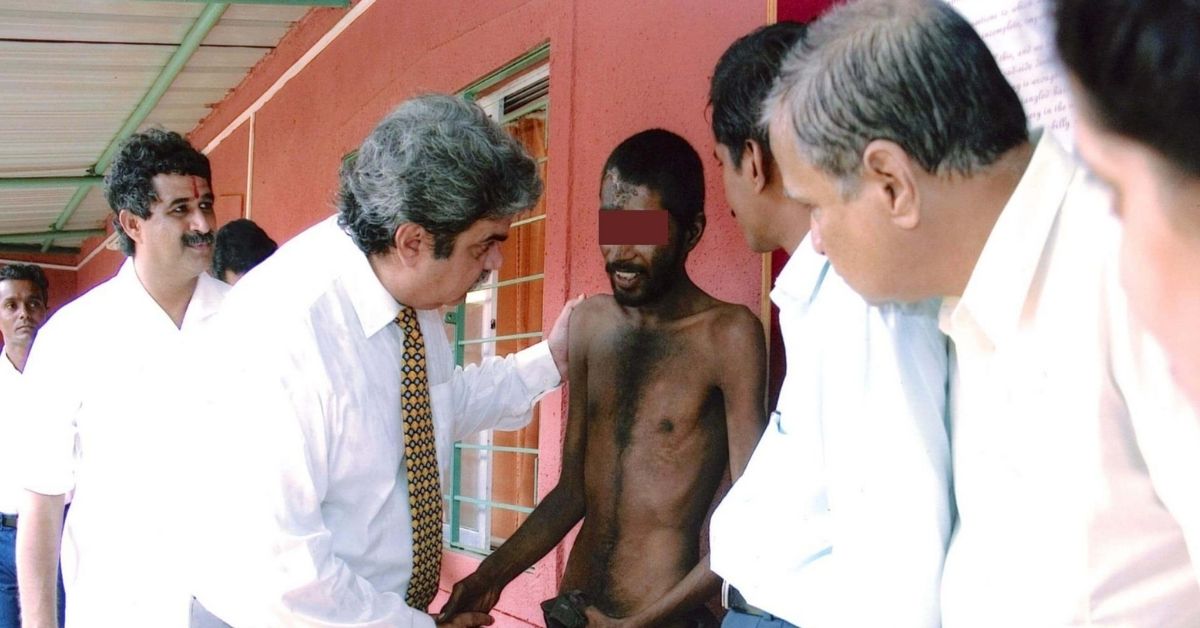

Dr Bharat Vatwani and his wife, Dr Smitha, run the Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation in Mumbai and Karjat, which aims to rescue and rehabilitate mentally ill patients off the roads, and reunite them with their families.

In 1991, Maniben was brought to the Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation by an elderly gentleman. She’d been sitting on the road with two children, with the younger one having passed away in her arms. Her mental illness had numbed her senses to the point that she had neglected to fulfill the child’s feeding needs. The smell of the putrefying body of the child drew passersby, including the elderly gentleman, who brought her into the centre. This was the first case of fostering a mother and child that the foundation came across.

The foundation is run by Mumbai-based psychiatrist, Dr Bharat Vatwani (62) who has many such gut-wrenching stories to tell. It aims to rescue destitute, mentally ill patients off the road and reunite them with their families. Since Dr Vatwani and his wife, Dr Smitha, began their work in 1988, they have rescued a total of 7,367 mentally ill patients, and reunited around 7,058 with their families.

‘The downtrodden in society are my brethren’

“I lost my father at the age of 12, and my brothers and I undertook the responsibility of making ends meet. Our mother was a homemaker,” Dr Vatwani tells The Better India. “We would do odd jobs, like selling posters of movie stars like Rajesh Khanna and Dev Anand to our classmates, running a circulating library, and selling books door-to-door.”

He further adds. “While my peer group seemed to be having the time of their lives, my brothers and I had to focus on earning a livelihood while balancing our academics,” he says, adding, “In retrospect, the loss of my father and subsequent hardships led me to resonate with the downtrodden in society. I looked upon them as my brethren.”

All through school and college, Dr Vatwani worked and studied harder than ever. Unable to afford tutoring, he says he studied for 14 hours a day to clear his degree in medicine. He met his wife, Dr Smitha Ganla, during his House-Post in Psychiatry at Cooper Hospital. “While, till today, I don’t know what qualities she liked in me, we got along like a house on fire and fell in love,” he recalls. The two married in 1987, and Dr Vatwani says their common concern for the underprivileged is what binds their relationship.

Shortly after marriage, Dr Vatwani and Dr Smitha were dining in a restaurant, when they noticed a skinny and disheveled young boy sitting on the road. “As psychiatrists, we could make out he was schizophrenic. We watched him pick up an empty coconut shell, dip it into the gutter flowing nearby, and drink the water. We were so gutted that we were crossing the road to help him before we could even think and brought him to our newly set-up private nursing home,” he says.

Mental illnesses don’t see social barriers

This nursing home had been set up by selling the jewellery Dr Smitha had received as gifts for her wedding and taking loans from banks with hypothecation of their property. “This unknown schizophrenic boy was our first admission. We nursed and treated him, and gradually, he improved. In two weeks, he started speaking English, and it turned out that he was a BSc graduate with a diploma in Medical Laboratory Technology. He’d come to Mumbai to hunt for a job, and had succumbed to mental illness upon not finding one,” says Dr Vatwani.

The couple wrote a letter to the patient’s father, who came down from Hyderabad, having been desperately looking for his son for almost a year. He was the Superintendent of a Zilla Parishad in Cuddapah district of Andhra Pradesh. “It was not a small position to be in, by any measure. Mental illness could affect the best of the best, and reduce a person to pathetically inhuman conditions,” he adds.

Dr Vatwani realised no organisation had been dealing with such patients at the time, so Shraddha was established soon after. It was registered as an official NGO in 1991, with the Vatwanis and their colleague Dr Ghanshyam Bhimani as the three trustees. In those days, roadside destitutes would be put up in their private nursing home along with other patients.

Over the years, as word spread about Shraddha’s endeavours, funding increased and more people became involved. In 1993, the organisation held an art fundraiser at the Jehangir Art Gallery in Mumbai, wherein around 140 leading Indian artists donated their creative worth for Shraddha’s cause. In 2006, the foundation built its new institution in Karjat to house more patients.

Among the patients is a young woman who was involved in a custody battle for her son with a famous Bollywood director. In 2019, the Borivali Railway Police brought in a woman named Madhavi (name changed), along with a young boy, who had a few wounds on him .“Her in-laws’ home was in Kanpur, and under the stress of her mental illness, she ran away with her child to return to her parent’s home in Bihar,” recalls Farzana Ansari, a social worker with Shraddha. “But she ended up in Mumbai.”

The then one-year-old baby was later taken by the police and handed over to the Child Welfare Committee (CWC), Mumbai, and eventually placed in the foster care of a Bollywood director. Over this time, Madhavi’s health, through nursing and treatment at Shraddha, improved rapidly. Her family had been contacted, and her father was ready to come from Bihar to take Madhavi and her boy back home. But during this time, the director’s family had grown quite attached to the boy. The director then engaged in a 15-month custody battle with the mother. Madhavi had by now received a fitness certificate and was ready to take her child back.

In December 2020, the court finally ruled in favour of the mother. Farzana, who worked with Madhavi at every step, says that she was a personal witness to the mother’s transformation. She called her recovery a miracle. Former Additional Solicitor General of India, Indira Jaising, was among those who fought for the baby to be returned to the young mother. This case highlighted a rare win for the rights of the mentally ill.

Boothnath Ram, Madhavi’s father, says they fought long and hard to get the mother and son home. “I’m grateful to Shraddha that they reunited us. Madhavi now takes her medication on time, and her son is around three years old. Both mother and child are doing extremely well,” he tells The Better India.

A worldwide phenomenon

Dr Vatwani says that when it comes to the rehabilitation and rescuing of female patients the foundation faces a particularly hard time. They first realised this in the case of Maniben. “After she recovered, she told us she lived in Baroda in Gujarat. When we arrived there, no one recognised her. Locals in the area mentioned names of nearby villages where the dialect she spoke was prominent. We moved around in the car for two whole days, but couldn’t find her family. We realised the ground reality that women in rural Indian are often so illiterate that barring the name of their village, they have no idea of where they actually come from. This continues to hamper our reunions even today, 30 years later,” he says.

“My wife, being a woman herself, finds it difficult to part from recovered female inmates if their families cannot be traced, because she often worries about what exploitation these women could be subject to. The number of women who have recovered but remain in our care is increasing,” he adds.

Lack of community support, financial constraints, the reluctance of families to accept the destitute because of fear of social ostracisation and supervision of timely medication once the patients are back in their hometown are just a few of the many more problems the foundation faces. Even social workers with Shraddha have to face harrowing circumstances at times. They have been bound and treated roughly by a patient’s relatives until the foundation’s credentials were established, and accused of kidnapping and human trafficking. Undeterred, Shraddha carries on.

In 2018, Dr Bharat Vatwani received the Ramon Magsaysay Award for his dedicated efforts to provide a new lease of life to the mentally ill destitute. But the doctor feels he didn’t do enough. “I could have done more. I should have done more,” he says, and points to the Population Census 2011 of India. “Around 1.8 million people in India [0.15% of the country’s population] are homeless. Studies have shown that the incidence of mental illnesses in the homeless is around 50-60%. So that’s almost 1 million Indians who are homeless and mentally ill. We’ve picked up, treated, and reunited around 8,000 of them. That’s a fairly insignificant number, given the magnitude of the problem.”

He adds, “I accepted the award in the hopes that it will highlight the plight of the wandering mentally ill, not just in India, but even across Asia, and the world. When we went to the Philippines, we saw the mentally ill wandering on the roads, and the psychiatrists we interacted with acknowledged it was a problem. It’s a worldwide phenomenon.”

Dr Vatwani says many such centres need to be set up across India to tackle the problem on a mass scale. “We need more initiatives to take the reins, but in the rehabilitation-reintegration model that we use. The question is not of how many wandering mentally ill are sheltered in how many NGOs, but of how many of them find their way back home, in a better psychiatric state,” he adds.

In a preface he wrote for the Marathi translation of a book on mental illness, Dr Vatwani says, “It is paradoxical that in a country full of apparent religiosity with multiple Gods….very few of us actually strive for the equality that Ambedkar has ascribed to religiosity in his book (The Buddha and his Dhamma)…For a country like ours, one does not strive to give equality to…their fellow-brethren citizens, who have mental illnesses, and it amounts to nullifying religiosity itself…Don’t just understand mental illness. Feel their pain too. For this could be me, this could be you, this could be us.”

Edited by Yoshita Rao

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167