Meet The Award-Winning Ladakhi Porter Who Saved Jawan Lives in Siachen

"At those heights, people are in danger all the time. Stanzin Padma was definitely among the most important assets we had there,” says a senior army officer.

Since 1984, when the Indian Army took control of the Siachen Glacier, residents of the surrounding villages in the picturesque Nubra Valley have been employed as porters. Their work involves carrying loads upto 20 kg to army posts on the glacier, stocking the posts with provisions, maintaining kerosene reserves, fixing ropes and ladders to assist soldiers in climbing the glacier and digging out the ice that soldiers melt into water.

(Image above: Stanzin Padma, the porter who saved many lives in Siachen)

At altitudes ranging as high as 22,000 feet above sea level and temperatures dropping to -40 degrees Celsius, where basic tasks like breathing, walking, eating and drinking are arduous, these porters have become the lifeline of soldiers serving there. Their keen understanding of the terrain has made them indispensable for the armed forces during search and rescue operations after commonplace incidents like avalanches.

“These porters double up as guides and scouts on various locations. They take care of logistics on the ground. For example, there are locations where you can only traverse by rope, and this requires real knowledge of mountaineering. They go to places where our boys cannot. Also, if there is a medical emergency, they are the first people to help and evacuate soldiers. Their role is critical by virtue of their experience and the fact that they are well acclimated to the conditions there. What they are doing there is selfless service,” says a senior officer of the Indian Army, who didn’t wish to be named, in a conversation with The Better India.

One such individual was Stanzin Padma, a 31-year-old former porter, who was not only involved in the rescue of two Indian Army jawans but also retrieved the bodies of deceased soldiers and fellow porters during his decade-long stint.

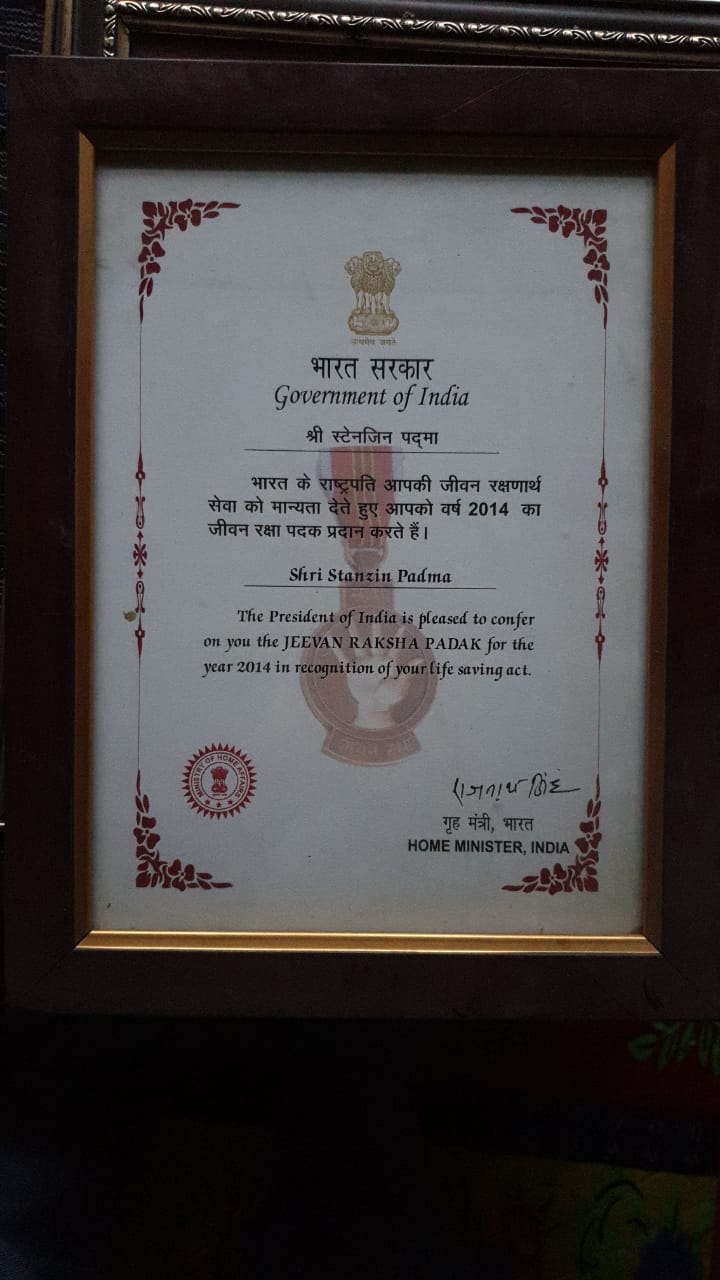

A recipient of the Jeevan Raksha Padak, an award given by the Union Home Minister “for courage and promptitude in saving life under circumstances of grave bodily injury to the rescuer” in 2014, Stanzin speaks to The Better India about his life serving in Siachen.

Hard-Knock Life

Born in Phukpochey village near the hot water springs of Panamik in Nubra Valley, Ladakh, Stanzin grew up in a modest farming household. Completing his high school from the Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalaya in Leh 14 years ago, he first worked as a part-time porter for the Indian Army in Siachen in 2006, while also doubling up as a tourist guide for trekkers to Markha Valley and Zanskar.

Although both his parents were farmers, his father occasionally took up work as a porter in Siachen as well. “The reason I took up work as a porter was because our family was undergoing some financial troubles, and instead of adding to their burden, I felt it was best that I contribute. From 2008 onwards, however, I began regularly working with the Indian Army until 2016,” says Stanzin, in an exclusive conversation with The Better India.

“Most youths in this region find work as porters on the Siachen glacier, but unfortunately, many have lost their lives. During rescue missions, we (experienced porters) are given the opportunity when others have failed, or it’s deemed ‘too late’,” he notes.

Deemed as casual paid labourers (CPL), these porters are paid a daily wage according to the grade of the post. There are approximately about 100 posts on the glacier that are classified into five grades based on their altitude and the risks involved in serving there. They are paid a maximum of Rs 857 per day at higher posts, while those serving at the base camp are paid Rs 694 per day. These figures haven’t changed since 2017, notes Padma.

These porters can only serve three months a stretch owing to brutal weather conditions, avalanches, crevasse and the threat of shifting ice. Since CPLs are eligible to make claims for permanent positions and pay after working for 90 consecutive days, the Army sends these porters in cycles of 89 days.

There have been times when after working 89 days, Stanzin comes down for a couple of days, gets a thorough medical check-up at the local government hospital and then climbs back up as soon as possible.

“Every year, I was up in Siachen at least three-four times a year,” notes Stanzin.

“Initially, the army would assign me to any camp they wanted. In 2012, however, I was taken to Kumar Post (16,000 ft above sea level), where I was also given the task of supervising other porters, create a muster roll for their payment, take note of how long a certain porter stayed at a given camp and send all that paperwork to concerned officers. Before me, another senior porter was supervising their work,” says Stanzin.

Challenges and rescue/retrieval work

With little to no training from the army for the high-risk environment in which they work, these porters function under extremely challenging conditions sometimes at the cost of their lives.

“Temperatures can drop to -40 degrees Celsius, while we also have to navigate avalanches, deep crevasses and shifting ice. Before the ceasefire in 2003, porters like us would even have to navigate enemy firing. Porters climb up to the post just below the highest one manned by the Indian Army. We often work during the day, but on days, when the weather is bad and snowing heavily, we sit inside our tents,” says Stanzin.

It has been extensively reported how some of the more dreaded medical conditions in these conditions are dehydration, high altitude cerebral oedema and high altitude pulmonary oedema, amongst others.

Like soldiers, Ladakhi porters too face the same risks.

Stanzin recalls the time he fell into a deep crevasse and miraculously survived in 2012.

“I was posted in the Sia-la area (above 18,000 feet Above Sea Level) when I got the call to transport some rations immediately to a higher post. Facing food shortages there, we had to transport rations. Unfortunately, we were also suffering from inclement weather. While I did manage to reach the designated post and transport the ration, on my way back, I got lost because of low visibility. After a few hours, my snow scooter got stuck in the snow,” he recalls.

With his scooter stuck, he began to walk. However, as he began walking down, he fell into a deep crevasse. This happened on 12 January 2012.

“When I regained consciousness hours later, I realized that I was deep down inside the crevasse. It was completely dark. I was lying flat but fortunately had no major injuries. Also, I had a wireless set with me, and so I tried contacting my fellow workers. It wasn’t until the following morning when the rescue party found the abandoned snow scooter that I had left behind. Throughout the night, I kept calling them to inform them that I am still alive, besides trying to keep myself awake. I couldn’t sleep the whole night,” he recalls.

When the rescue team pulled Stanzin out of the crevasse with a rope, he had frostbites on four of his fingers. Fortunately, he didn’t have to amputate them.

In the following December, however, it was his turn to save a fellow porter, Nima Norboo, who had fallen into a 200 feet deep crevasse. Stanzin’s job at the time was to coordinate the work of porters posted at the glacier, and he had received news one afternoon of how one of his colleagues had fallen into a crevasse.

Despite their efforts, the first set of the army and civilian rescue teams had given up on the search. But Stanzin was determined to find his colleague and spoke to the commanding officer, who arranged a helicopter the following morning.

Rescue teams were aware of the exact location from where the person fell-down but the crevasse was very complex and narrow. Beyond a certain point, rescue teams couldn’t lower themselves down any further.

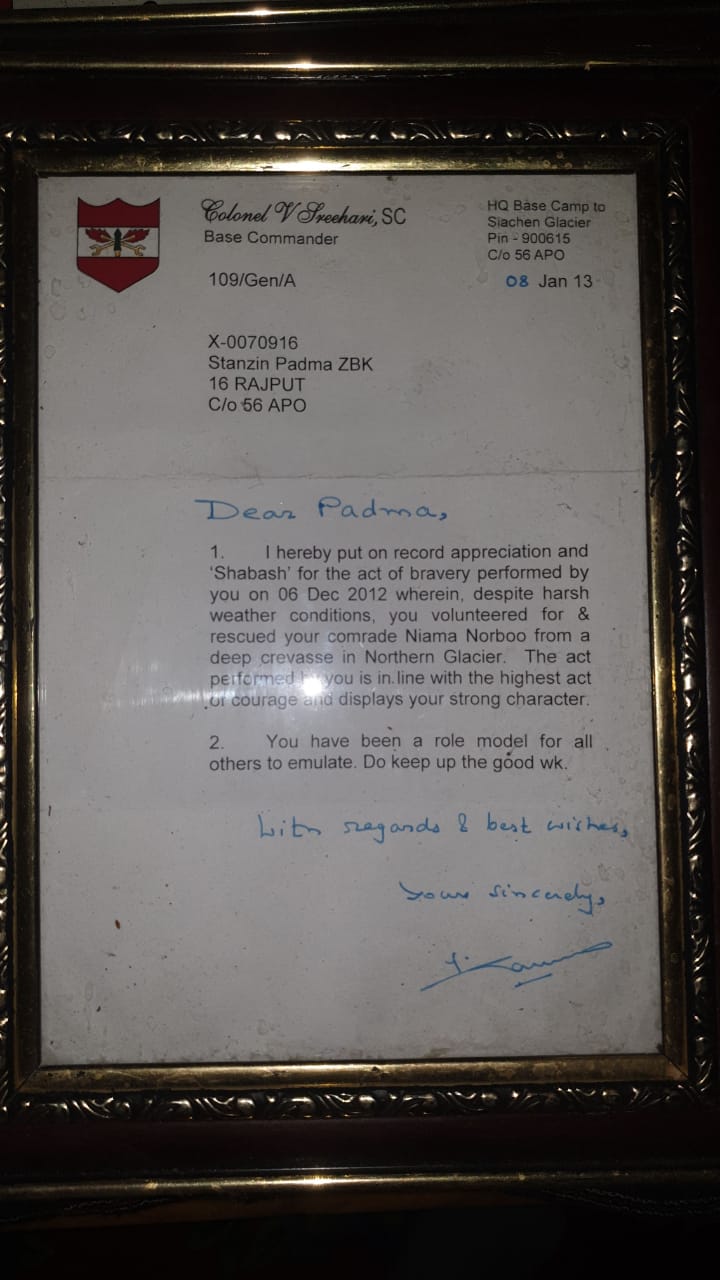

“When a person falls, it is easy to slip-down through narrow gaps. Secondly, crevasses may have multiple branches within. So, it becomes difficult for the rescue team with full gear to pass through these narrow gaps. But I took advantage of my lean body and climbed down alone with the necessary rescue gear. Initially, I was under the impression that Nima must have died, but as I climbed down, I could hear him calling for me. He had an injury on his head. When asked why he couldn’t call the rescuers the previous day, Nima told me that he regained consciousness in the middle of the night. Anyway, I rescued him out of the crevasse, although he lost one arm and both legs below the knees. The rescue operation (on 6 December, 2012) took hours to complete, requiring real patience and perseverance,” says Stanzin.

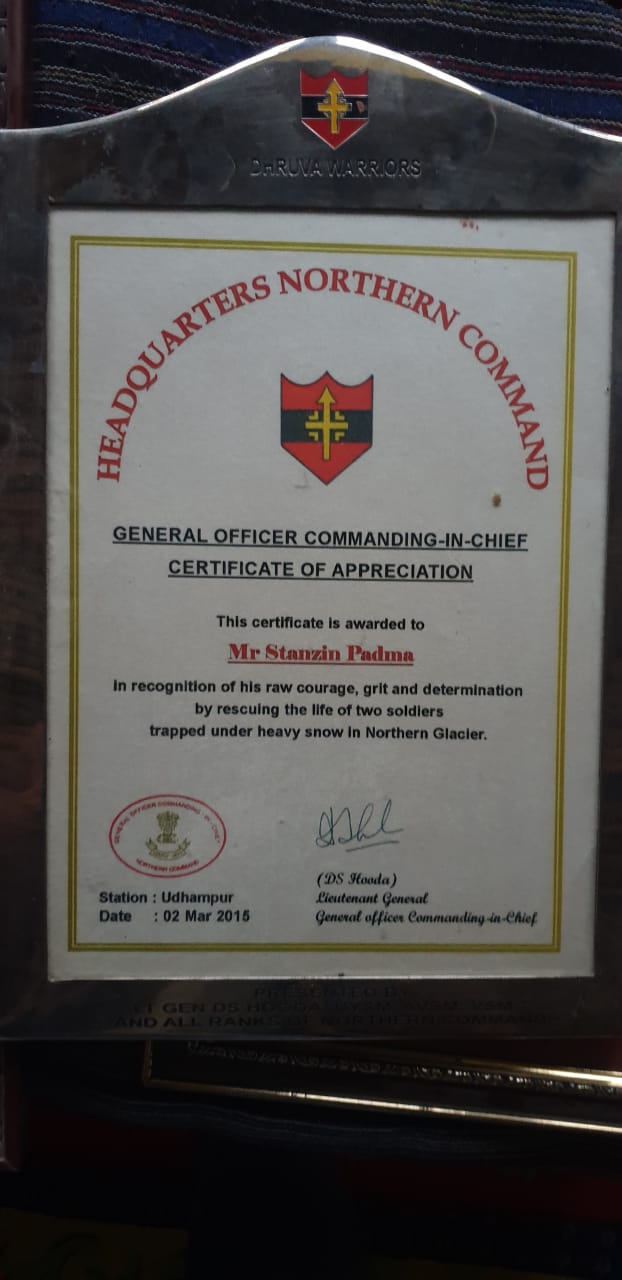

However, his shining moment came a couple of months later, when as a part of a five-person team, he saved the lives of two jawans stuck under an avalanche at a forward post called Tiger LP (21,500 ft above sea level).

In late May 2013, five soldiers on duty were buried under an avalanche one night. “There were five of us, including an officer of the Indian Army, as part of the rescue crew. Initially, we took out snow scooters, but since the weather was bad, we couldn’t drive them properly. So, we abandoned the scooters halfway and went up walking. However, while climbing up, we got hit by an avalanche, and all of us got buried inside. When the avalanche subsided, I realized that my whole body was buried inside and I couldn’t move an inch. Luckily, one of our teammates was only buried below the waist. He managed to free himself and rescued all of us. We decided to return to our post and to resume the rescue mission next morning as the weather was bad. Moreover, we were tired and scared too,” recalls Stanzin.

The next morning, they went to rescue them. Upon reaching the site, they realized that all five were buried inside the tent. They uncovered the snow and found that only two of them were alive.

The survivors were immediately flown down to the army hospital for resuscitation. A year later, all of them were bestowed with commendation certificates on army day in Akhnoor.

Stanzin does admit to the pain of seeing soldiers and colleagues losing their lives as he went up to retrieve their bodies. In February 2016, when the 40-year-old porter Thukjey Gyasket fell into a crevasse, Padma was immediately flown in to be a part of the team that recovered his body since the army rescue team couldn’t find him.

“The crevasse was so narrow that I could barely fit through it. I think the other rescue team couldn’t pass through it and hardly imagined that the Gyasket must have passed through it. I saw his body lying deep down the crevasse. The injuries were severe, and seeing his body did pain me. However, there have been occasions as well when I was involved in saving the lives of soldiers who had fallen critically ill in the nick of time,” he says.

“Stanzin is a multi-faceted chap. Despite his position as the head porter there, he handled a whole host of other things as well like repairing small generators stationed in each post and snow scooters, which are the lifeline for our soldiers serving there. Besides having technical knowledge of such equipment, it’s tough to work on them in those inhospitable conditions. But whenever a generator went bad, he would come with me and repair them all through the day. He also held a good command over all the porters working there. At those heights, people are in danger all the time. The other person has to really trust you with his life to listen to you. He earned the trust of the people there. He was definitely among the most important assets we had there,” says the senior army officer.

After working as a porter in Siachen for nearly a decade, Stanzin took up work with a trekking agency and even served as a manager of a Nubra-based hotel. He continues to work in the tourism sector, while also starting as a contractor.

“Despite the pride, I found working as a porter with the Indian Army; the fact is our job is not well recognized, and civilians don’t care about us. I feel that if we get the facility to cast our vote through postal ballot while we are working as porters at the glacier, I think our politicians will take care of us. Well, I am hopeful at least,” says Stanzin.

(With valuable inputs from Dr. Nordan Otzer)

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167