The Legendary IFS Officer Who Adopted a Tigress As His Own Daughter

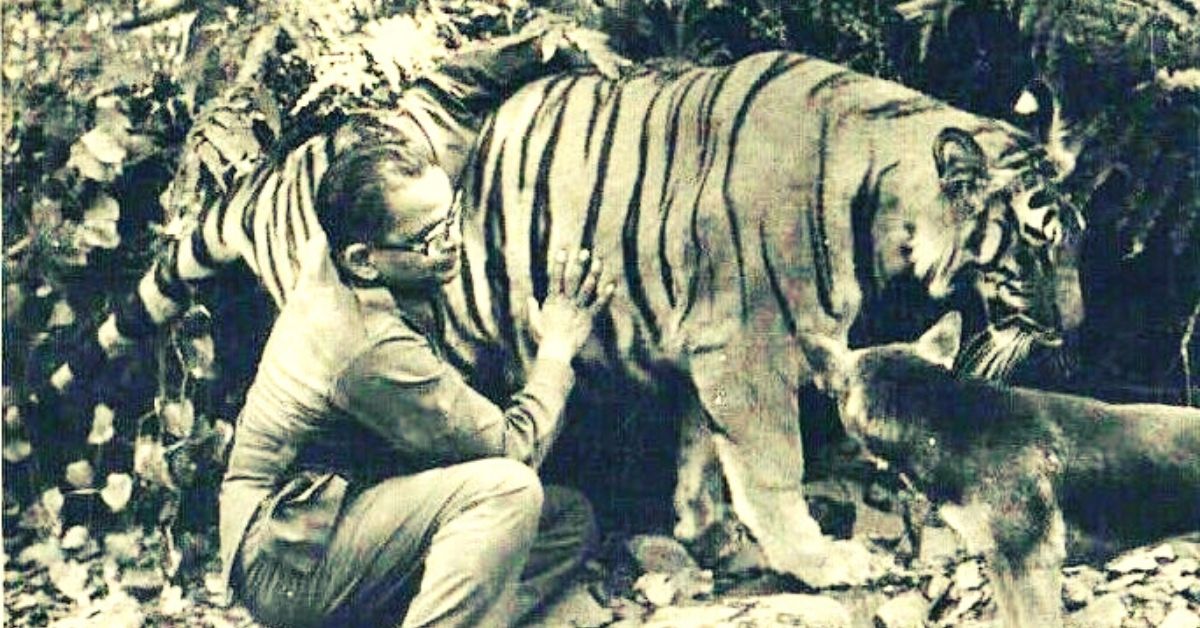

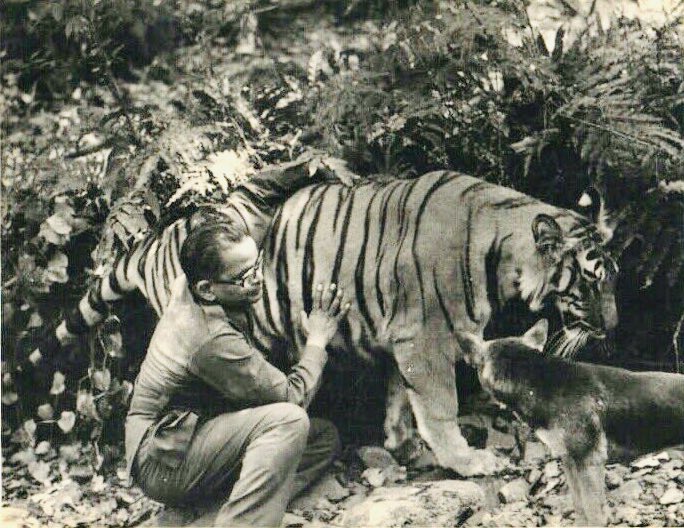

As Khairi’s foster parent, Saroj Raj Choudhury would feed her with his hands, play with her and even sleep with her mighty paws on his chest.

On 5 October 1974, a female tiger cub was brought to Saroj Raj Choudhury, the founder Field Director of the Similipal Tiger Reserve in the Mayurbhanj district of Odisha, which lies on the fringe of the Eastern Ghats. The cub was found unattended near the Khairi river, by the members of the Kharia tribal community, who were collecting honey from the core area of the tiger reserve. This was the start of a special seven-year relationship between one of India’s most important wildlife conservationists and his beloved tigress Khairi (named after the river), which caught the attention of the national media and wildlife enthusiasts from around the world.

Khairi became a ‘free-living family member’ at Choudhury’s official bungalow in Jashipur, and also established a close bond with cousin sister, Nihar Nalini. She was fed with mutton and milk powder, slept on their beds and often played with them. Choudhury also closely observed her to study the various behavioural aspects of tigers, especially the use of pheromones, their mating behaviour and territoriality, among others.

However, long before Choudhury took over as the Simlipal Tiger Reserve’s first Field Director and met Khairi, he had already established himself as a pioneer of wildlife conservation, particularly of tigers, in India. From developing the pugmark tracking technique, which was the bedrock of organising tiger censuses in India till 2004 and the foundation of India’s much vaunted Project Tiger initiative, to mentoring generations of forest officers in the finer nuances of wildlife conservation, Choudhury remains a legend to this day.

Early Days

Born on 13 August 1924, in a village near Cuttack, Odisha, Choudhury grew up amidst wildlife, including tigers.

“Those were the good old times in the thirties during my school days, when the tiger used to live in the vicinity of our rural home,” he writes in his 1978-79 academic paper Predatory Aberration of the Tiger.

Choudhury started his career as a forest officer in the Government of Odisha on 1 April 1949 and rose through the ranks to become its first Wildlife Conservation Officer in 1966. It was only by the 1960s, when he became a prominent figure in wildlife conservation.

“Few people know that he eliminated a number of man-eaters in Odisha during the 1960s, thus saving both local lives and other innocent tigers from public retaliation. Choudhury was an accomplished officer before Khairi came along and after spending significant time in the field in Odisha, where he oversaw a rigorous tiger census in 1968, he went on deputation to join the Forest Research Institute, Dehradun as a Senior Research Officer. Apart from training a large number of forest officers in wildlife management, it was here that he further developed and refined his pugmark census technique which eventually led to a comprehensive document and guide on it that was published in Cheetal, the journal of Wildlife Preservation Society of India, in 1970. He then returned to his home cadre of Odisha with the beginning of Project Tiger in 1973 and became the founder Field Director of Similipal Tiger Reserve,” says Raza Kazmi, a wildlife historian, speaking to The Better India.

A Mentor to Many

LAK Singh, a retired senior research wildlife officer with the Odisha government, was invited by Choudhury in 1979 to conduct a thorough survey of Similipal rivers for rehabilitation on mugger crocodiles. Singh came in close contact with him and his assistant Conservator of Forests in the 1970s. Speaking to The Better India, he mentions how Choudhury laid the foundation of wildlife conservation in India.

“Many forest officers consider him as the father of Wildlife Education in India, because he started the training programme on Wildlife Management, at the Forest Research Institute in Dehradun,” he says.

For example, Fateh Singh Rathore, a highly respected forest officer responsible for making the Ranthambore National Park the “place which brought the tiger to the consciousness of people the world over,” according to the World Wildlife Fund, had studied under Choudhury at FRI.

Describing Choudhury’s approach to teaching, Soonoo Taraporewala, who authored Fateh Singh’s biography titled Tiger Warrior: Fateh Singh Rathore writes:

“Choudhury himself loved fieldwork and appreciated the knowledge gained by working on the ground as opposed to the theory studied in the classroom through lectures and textbooks. He took his students to several areas around Dehradun such as Khara, Chhila and Mundal along the Ganga, all now part of the Rajaji National Park. The training proved to be tough, with nearly two months spent tracking animals, and maintaining diaries. Such a discipline process is of immense value to anyone who intends to work at protecting wildlife, because without meticulously kept records, one cannot hope to draw an accurate picture of the state of wildlife in an area.”

“These officers then went on to become effective field workers in their respective states. He also was a meticulous planner and laid down the inaugural protocols for preparation of management plans for each tiger reserve and other protected areas as well as the layout of forest roads, habitat management, tourism control and so on. All subsequent developments in these fields over the years were made on those initial blueprints that Choudhury and his colleagues prepared in the late 1960s and 1970s,” adds Raza Kazmi, speaking to The Better India.

Even after Rathore graduated from the FRI and made his way to Ranthambore, Choudhury continued to mentor him.

“Fateh’s mentor, Choudhury, visited him frequently in Ranthambore, and would advise him on road and construction work. He stressed that the texture of the land should never be changed, and that the roads should skirt water only at a few points, so that animals could have undistributed access to it. The roads were to be planned through all kinds of terrain, winding routes, on which the maximum speed should never exceed thirty kilometres an hour, Choudhury would tell Fateh. This sound guidance was followed meticulously, and the results manifested themselves brilliantly as the forest regenerated and animals returned to their habitat, making it one of the most magnificent natural areas in the country, with a wide variety of landscapes,” writes Soonoo.

It is imperative to note that at the time, wildlife was not considered a glamorous field. Despite the little media attention or lack of significance attached to wildlife conservation in the larger public discourse, Choudhury worked relentlessly to mentor future generations who would go on to carry his work forward.

“Today, wildlife study has a certain charm. People love to see photographs of wild animals, and understand them. That wasn’t the case back then. Those were the days of territorial forestry — the forestry of harvest, sustainable yield and plantations. In the old days, thrown in the deep end of areas with extensive wildlife was sometimes considered a punishment posting. Moreover, the modes of communication and mass media were quite rudimentary and news about local wildlife wouldn’t reach the masses,” says Ramesh Pandey, a 1996-cadre Indian Forest Service Officer currently serving as Director, Delhi Zoo.

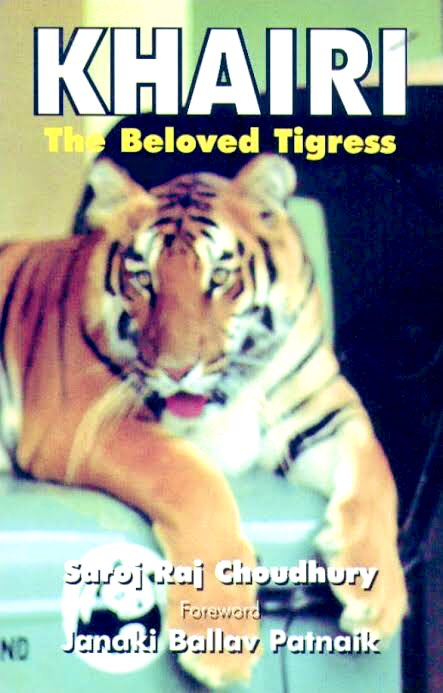

The touching story of Khairi is immortalised in ‘Khairi The Beloved Tigress’ where aspects of tiger behavior, like territorial markings by spraying uric lipid pheromones as a sign of territory deduced. Khairi still roars in Simlipal jungles as the legends never die…? (4) pic.twitter.com/fVYgdFhCrZ

— Sandeep Tripathi, IFS (@sandeepifs) July 12, 2020

Pugmark Census & Project Tiger

Wildlife conservation in India really took off in the early 1970s, which saw the enactment of the Wildlife Protection Act (1972), the establishment of Project Tiger (1973), signing onto the Stockholm Declaration (1972) and Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of Wild Fauna and Flora (1973).

By 1971, opinion was unanimous that the tiger population had drastically gone down. While the population of tigers was estimated at around 40,000 at the beginning of the 20th century, excessive hunting and poaching had resulted in a significant drop. But how could one measure that drop in population?

“Understandably, there was no scope to enumerate tigers by direct count. We all know that tiger-sighting is heavily dependent on ‘luck,’ and that before we see the tiger once the tiger would have seen us a hundred times. Yet, we know of evidence that speaks about the presence of tigers. Some of the main evidence include kills, scat, pugmark, ground-scratches, tree-scratches etc. Among all these field evidence, pugmarks are the most common, most revealing and the easiest to use,verify and interpret to produce reliable information on the minimum number of tigers,” says Singh.

Nobody knew how to measure the population of tigers using their pug marks until Choudhury devised a simple instrument called the Tiger Tracer in 1970.

“It’s a glass plate with a small wooden frame, which is placed on the footprint. The outline is drawn, transferred to a transparent sheet of paper, and from the field the footprint is brought to the laboratory for storage, further analysis and retrieval,” adds Singh, while explaining the Tracer.

The first All India Census of Tigers was conducted in summer, 1972 using Choudhury’s method with the Tiger Tracer. As per the Census, there were about 1827 or 1840 tigers left in the country. From that census, areas were identified where tiger reserves should be established. Nine tiger reserves were initially chosen measuring upto 16,000 square km in area, amongst which Simlipal was one. From 9 it has grown to 50 tiger reserves today measuring up to 70,000+ square km.

“I think Choudhury’s biggest contribution was the development of the pugmark census technique and the management of Similipal Tiger Reserve under his tenure which was the golden period for this primary tiger habitat in Orissa. His technique was the bedrock for tiger census right uptil 2004 after which we shifted to camera-trap census. And while the pugmark census technique came under criticism in later years, it was in view primarily because the strict protocols and skill sets that Choudhury had made a prerequisite for successful application of his technique were either overlooked or poorly implemented leading to problems. Even today, his pugmark census techniques are a great supplementary monitoring technique for tigers in addition to the camera-trap technique,” notes Raza.

Although Choudhury is credited with inventing and developing the pugmark technique of counting the tiger population, it was the likes of LAK Singh, who went on to further refine it.

After his research stint with crocodiles in Mahanadi in the ‘70s, and Chambal in early 1980s, Singh was back at Simlipal in 1987. For the next 16 years, he would go on to refine the technique using not just the Tracer to mark out the pug mark or build a cast made of plaster of paris capturing its exact dimensions, but also a conglomerate of over 30 field and track parameters on Census Form-D, deliverable by skilled village-level trackers or Forest Guards without college degrees.

“Pugmark tracking gives you quick results, composition of the population, territorial patterns, demographic relations among species, their male-female-cubs, and it preserves the traditional skill of the people. Tracking is the skill of the people living in forests and the entire operation utilises the services of the local people. In the 1990s, we were getting about 1,000 pug marks through either Tracing or Plaster of Paris at the Simlipal Tiger Reserve. We were reducing that number by discerning and eliminating the overlapping pug marks and thus obtaining the minimum male-female-cub tigers, what is their movement area, how many female tigers have cubs ranging from newborn to a two-year-old, etc,” says Singh

Before the actual census starts, the forest department would make PIPs or Pug Impression Pads.

Upto 10 cm of the dry path or track is dug up to make a strip measuring 2m long x total width, where the earth is collected in one place. Then the census unit personnel including trackers and foresters use a wire mesh to sift a layer of fine dust on the marked strip, level the dust after the area is filled and place rocks or branches on the side to prevent bypassing of PIPs by tigers.

“In Simlipal nearly, 4500 PIPs were designed at one time. Each one was like a camera. Anything that walks over it is registered. It also gives a lot of information about which direction the animal is going. We also gave a lot of training to forest staff. Before the start of a tiger census, PIPs are set up, census units are established and each one is led by a forest guard. Since we don’t have enough forest guards, experienced trackers from the local community also become unit leaders. One leader and backed by 2-3 assistants. Some non-official members would also join from local NGOs as witnesses to the process,” informs Singh.

The pugmark census is done over six days through the last week of December and first week of January. In Simlipal there were 75 census units, and each one covered 3-4 census routes.

Relationship with Khairi, the Tigress

Choudhury not only taught India how to count tigers, but also loved and studied them deeply. Nothing defined his love for tigers like his unique bond with Khairi, but he was also equipped with the necessary skills to study her from a scientific viewpoint. He would spend days in the forests with Khairi, observing her from close quarters.

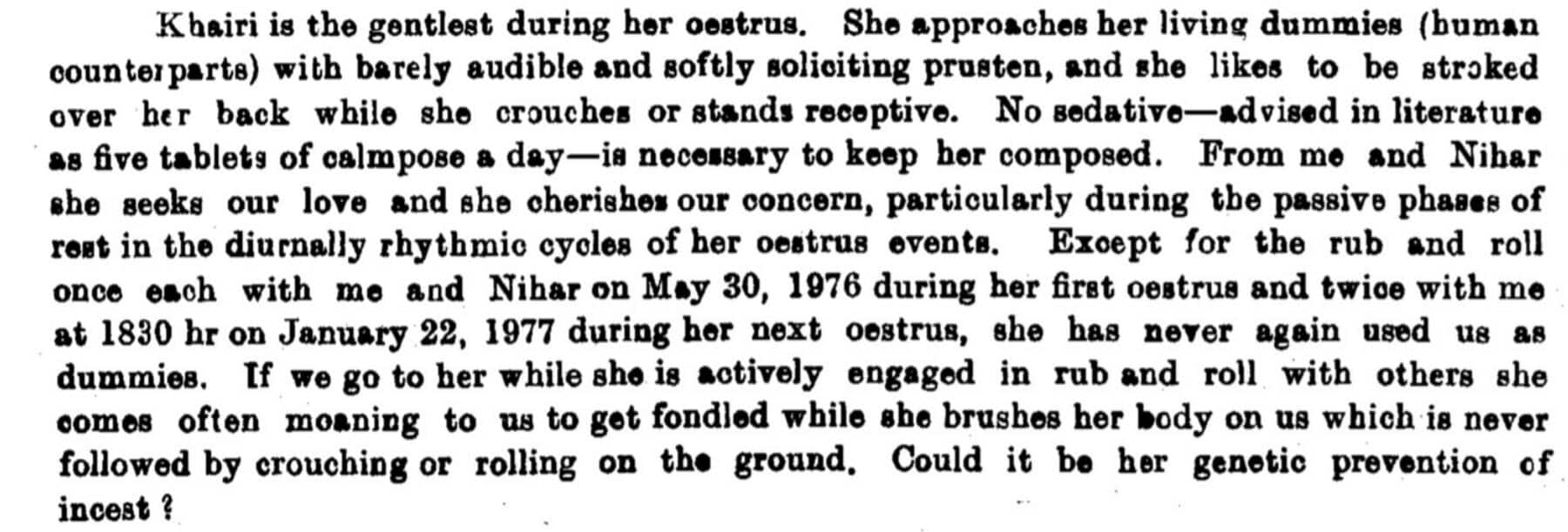

Sample this from Choudhury’s 1980 research paper published in the Indian Forester, titled Olfaction Marking and Oestrus:

“There are people who are known to have kept tigers, lions and leopards, but nobody took down data so vividly 24 hours a day like he did with Khairi. Of course, forests guards and other department staff were enlisted for that work as well, but Khairi was also like a research subject to him. Nobody had done it earlier. His analysis was very different from the rest,” says Singh.

Besides Khairi, Choudhury also reared many other animals at his Jashipur bungalow like mongoose, hyenas, dogs and crocodiles in the adjunct campus of Ramatirtha on the banks of Khairi-Bhandan.

“Khairi was staying with other animals, sleeping in a bed alongside Nihar Nalini. She would often take care of Khairi, and the relationship Choudhury shared with the tigress was possible because of her work. However, one drawback of the entire experience was that Khairi ended up becoming a pet. Many times they tried to release her into the forest, but she kept coming back. She was never able to conceive as well,” informs Singh.

Khairi was barely seven human years old when she died in 1981. She had contracted rabies after being bitten by a stray rabid dog that had entered the premises of his bungalow, and had to be put to death through rare euthanasia.

“Choudhury was in Delhi for a conference at the time this happened and by the time he returned it was too late to provide an anti-rabies vaccine. Khairi was like his daughter and his entire personal life more or less revolved around her, so her sudden and cruel death had the same devastating impact on him as losing a child for a parent,” says Raza.

A year later and months before his retirement, Choudhury died on 4 May 1982, in his office, after a massive heart attack. Some say he never quite recovered from Khairi’s loss. He was posthumously awarded the Padma Shri in 1983.

“The legacy he leaves behind is real. Forest officers and conservationists working today have much to learn from him. He was completely dedicated to the wild , and took immense pride in being a forest officer. He always insisted on officers spending as much time in the field as they could, as there was no greater teacher and trainer for an officer than field work itself. Choudhury saheb was a complete field officer and would mostly be found camping in the forests of his jurisdiction rather than an office room. His personal conduct was exemplary. At the same time he was honest to the core and never shied away from either accepting failures or inviting outside expertise wherever and whenever needed,” says Raza.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167