It Took 1,100 Km To Find The Gond Adivasi Who Won Britain’s Highest Bravery Award

Forgotten by history, Amit Bhagat uncovered his amazing story nearly 95 years later—deep inside Naxal-affected jungles.

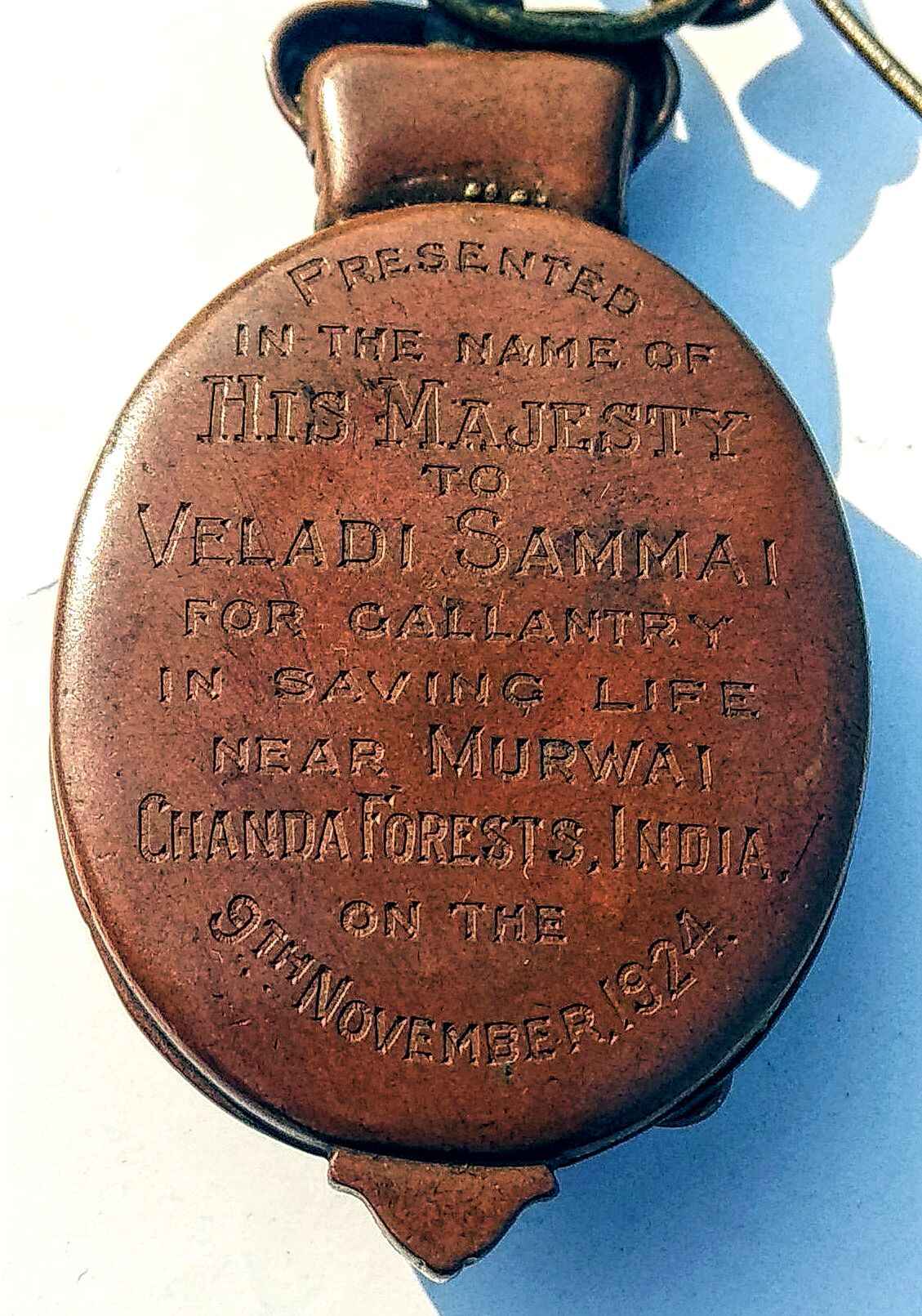

Do you know about Sama Veladi, a man of the Madia-Gond tribe from the deep forests of present-day Gadchiroli district, Maharashtra, who was conferred with the Albert Medal (Lifesaving) on 9 November 1924?

At the time, the Albert Medal was the highest peacetime gallantry award under the British Empire, and was conferred upon Sama by King George V for his incredible act of gallantry.

Sama was one of only two Indian civilians to ever receive this award, alongside a boatman named Gharib Shah, who had rescued 45 passengers from drowning in the Yamuna a decade earlier.

So, what happened?

According to the London Gazette report on 12 May 1925, HS George, the Deputy Conservator of the South Chanda Division (present day Sironcha tehsil of Gadchiroli district) of the Central Provinces, had just completed a forest inspection. He was returning to camp along a jungle path accompanied by Sama Veladi [referred to as Veladi Sammai in British news clippings], who was carrying George’s gun and walking ahead.

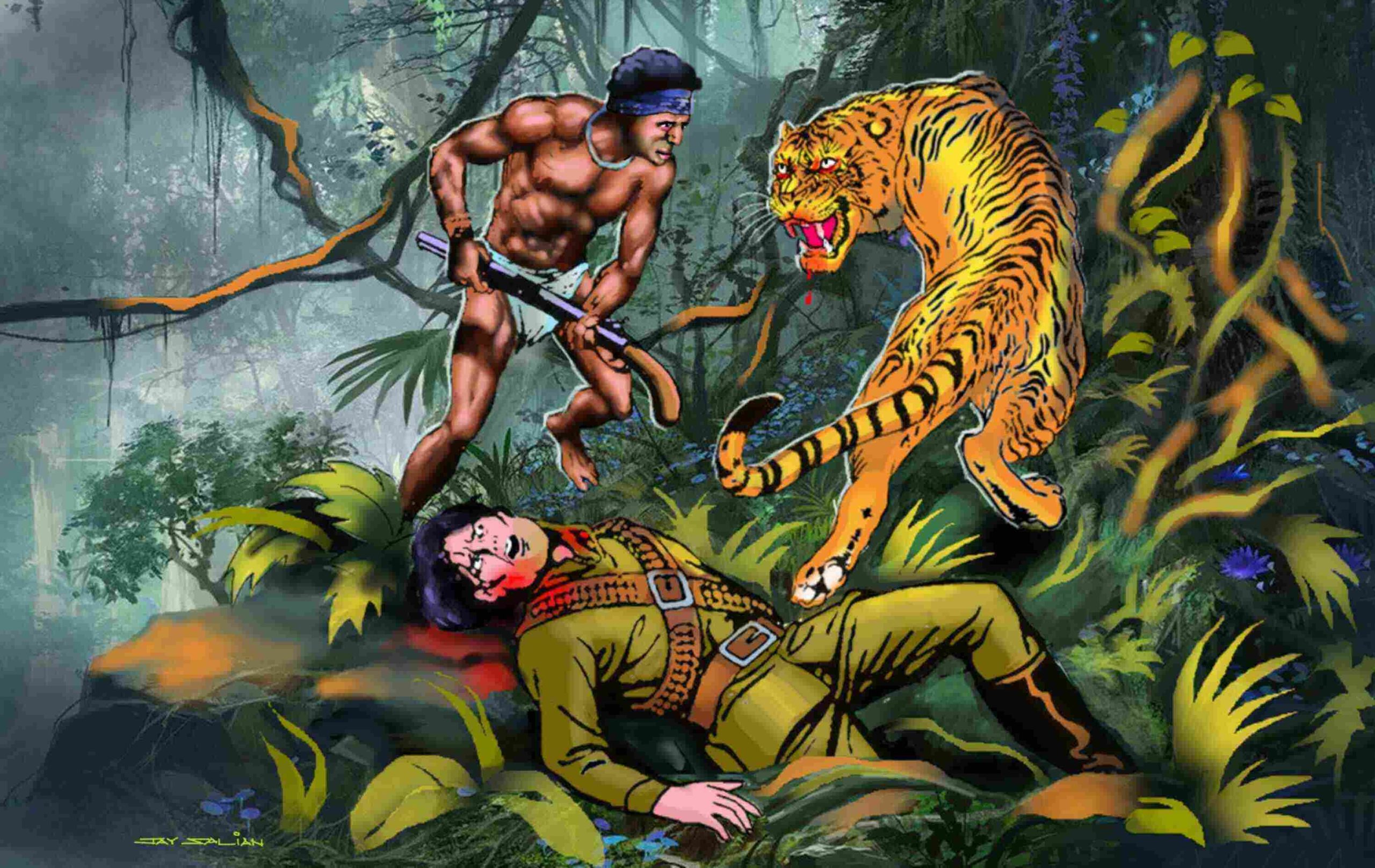

“Suddenly and without warning a man eating tiger jumped upon George’s back, seized him by the neck and proceeded to drag him into the jungle. Veladi Sammai behaved with extraordinary gallantry: he rushed at the tiger, placed the muzzle of the gun (a 12-bore shotgun) against it and pulled the trigger but was unable to discharge the weapon owing to the safety catch with which he was not familiar,” notes the report.

In the violent struggle that ensued, he resorted to beating the tiger with the stock of the gun on its head until the animal let George’s throat loose. It was an almighty struggle, and later, the tiger’s teeth marks were found eight inches up the barrel of the gun. He then shouted and waved his arms thus driving the tiger off for a short distance. After the struggle George got up, but collapsed immediately into Sama’s arms.

“Mr. Geroge was badly bitten in the neck and covered with blood with the Gond’s assistance he managed to stagger slowly along and reached his camp which was about two miles away,” adds the report.

During this whole journey, however, the tiger kept following Sama who was carrying George on his shoulders while running towards ‘Murwai Forest Village,’ the the nearest British camp. It wasn’t a simple journey as Sama had to navigate steep ridges and streams as quickly as he could while the tiger followed the scent of blood.

“The tiger followed them for some distance but was kept off by the shouts and demonstrations of the Gond,” reports The Guardian on 14 May 1925.

They somehow reached the camp at Murwai, where George was immediately taken into Chanda (present-day Chandrapur and capital of a district in the Central Provinces that also included present day Gadchiroli district) for treatment and subsequently to Mayo Hospital in Nagpur, where it took him 11 months to make a full recovery.

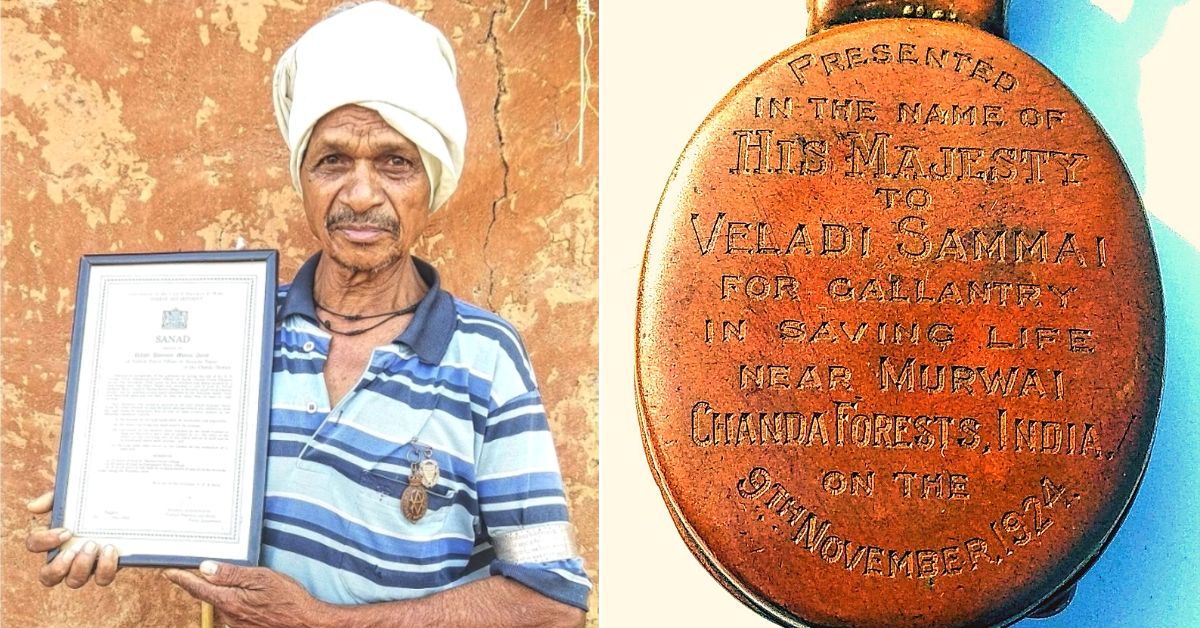

Sama was awarded the Albert Medal but since he couldn’t travel to London to accept the award, he was called to the provincial capital of Nagpur. He received it from the Governor of the Central Provinces, Sir Frank Sly. Reports indicate at the time that Sama showed up merely wearing his loincloth. So, instead of pinning the medal, the Governor gave it to him in his hands. Besides the medal, he was granted a silver belt and a silver armlet with his name inscribed on it as well.

Finding Sama Veladi

We would not know anything about Sama Veladi and his bravery, if it wasn’t for Amit Bhagat, a 33-year-old independent researcher who is also an administrative officer with the United India Insurance Company.

A Mumbai native, Amit was posted in Chandrapur back in November 2014. Aside from his day job, this history buff began visiting all the famous tourist sites in the district.

Tired of the conventional tours, he soon went into the jungles of the Chandrapur-Bhandara belt where he discovered eight megalithic (memorial consisting of a very large stone forming part of a prehistoric structure) sites, nearly 30 stone age sites and rediscovered a unique archaeological site on the cusp of encroachment by the State government, which wanted to build a Rs 1000 crore medical college and hospital.

Through his own extensive research, he rediscovered the long ignored pre-historic site of Papmiyan Tekdi inside the compound wall of the hospital. Located on the banks of the Jharpat river, a tributary of the Wardha River, the site was first discovered by LK Srinivasan of the Archaeological Society of India (ASI) in 1961. At the site, archaeological finds like stone tools and fossils date back more than 150,000 years.

In fact, this ancient region has a remarkable repository of archeological marvels dating back to the times of dinosaurs that roamed these parts nearly 200 million years ago. Evidence for the same came from finding dinosaur eggshells discovered in the nearby Pisdura area.

“Instead of meekly watching the destruction of this precious site, I wanted to save it and thus reached out to all the authorities, including the CM’s office. After a brief tussle with local authorities, including the State archaeology department and ASI, the Maharashtra Chief Minister took cognisance of my demand and allowed for the establishment of a museum displaying Stone Age tools and a preserved prehistoric site within the college sometime in November 2018. They even issued a grant of Rs 5 crore for the construction of a prehistoric park on that site. It would be the first prehistoric park of its kind in South Asia,” says Amit, speaking to The Better India.

Besides all this work, he even visited nearly 800 villages in these parts during the four years that he had been posted in Chandrapur as part of his research work. However, thanks to his confrontation with a State minister on the Papmiyan Tekdi issue, he was transferred back to Mumbai on 29 January 2019.

Now, posted far away from the region, he decided instead to dig into some British newspaper archives about the larger Vidarbha region.

“Even though the Gonds had ruled the hilly regions of Central India for 500 years from the mid 13th century to the 18th century (1751) either independently or as vassals of the Mughals, there were very few historical documents written about them. The only reliable source of their history was available in British sources. While going through a May 1925 edition of the London Gazette, I came across the short article about Veladi Sammai. The name of the village noted in the London Gazette, ‘Murwai,’ sounded very strange because I had never heard about it despite my extensive travels. But the story was so fascinating,” he notes.

During his research, he started digging deep and first discovered the work of sociologist Govind Sadashiv Ghurye, followed by Stanley Jepson’s book ‘Big Game Encounters’ and finally Brigadier-General RG Burton’s treatise, ‘A Book of Man-Eaters.’ All of them had briefly written about how Sama saved a British forest officer and was conferred the Albert Medal.

He also looked at British newspaper archives and found almost 10-12 such news clippings with the exact same story. Maybe, he thought, it was a news wire agency that may have supplied the report to publications in Australia, Scotland and Britain around May-June 1925.

This led him to believe that this was big news since it was covered by so many publications.

What followed was his research into the Albert Medal. First instituted by the Royal Warrant on 7 March 1866, the medal was named after Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, and was bestowed on those who performed extraordinary acts of bravery and risked their own lives to save others in peacetime.

But, besides the series of news clippings on Sama Veladi, there was no other record or mention of his act.

“In the newspaper clippings, there was a mention of ‘South Chanda Forest’. Since this nomenclature was defunct and didn’t exist presently, I collated the names of all villages in Chandrapur and Gadchiroli district—there were around 3,500 of them—but found no village named ‘Murwai’ which was the name mentioned in the British records. So, I decided to find names of villages that sounded similar like Murmadi, Murmuri, Murumbodi, and Morawahi, etc. There were around 20-25 of them,” he recalls.

He contacted all the forest officials in these parts and asked them whether they knew of this personality and such an incident ever happening. However, they replied by emphatically stating that had the incident happened in their areas of jurisdiction, they would have known about it. Unwilling to give up, he began researching the contact details of retired forest officers who had served in the region in the 1960s and 70s. However, they too, had never heard about this incident.

“How can they not know of such a big incident? The antique medal he was awarded was a matter of pride for our country and to the forest-dwelling Gond tribe. So, I then contacted the Tribal Research & Training Institute in Pune, and its director. When I asked him, he had no idea, and instead gave me the contact of the institute’s library supervisor. I kept calling the supervisor for three months, but didn’t hear from him,” he recalls.

Breakthrough

He soon came across a retired Indian Forest Service Officer, VT Patki, who had retired as Chief Conservator from the Chandrapur region. Patki, who was in his 70s, he had once served as Divisional Forest Officer serving the Allapalli division of the Chandrapur district between 1978 and 1981.

While he had no information about the Albert Medal, and when that incident actually happened, he told Amit about a village named after a Britisher called ‘Georgepetha’ after the former British forest officer. On Google maps, it was called by its corrupted form ‘Jarjpetha.’

“This was my first major breakthrough since HS George was a central figure in this story. While scouting for the village, I finally came across Mudewahi, which was located deep inside the Aheri Taluka in Gadchiroli district, and was Naxalite territory. However, I packed my bags, arranged for a translator there who could speak their dialect of Telugu and native Madia Gond tongue, and began my 1,100 km journey from Mumbai to learn more about Sama Veladi,” says Amit.

Following a 26-hour journey, he arrived at the Range Forest Office of the Bamani Range, which is barely 15-20 km from the village. However, the range officer there told him that despite serving three years, he had never once visited the village because it was considered too dangerous. The last time he stepped out anywhere, somebody had burned down his vehicle.

“It had taken me a month to gather all the clues, but I actually went into that village blind not knowing whether it was the same village Sama Veladi encountered. Neither the forester nor the forest guard, who were deputised to go along with me and used to live in a nearby village, had ever heard of such an incident ever taking place nearly 100 years ago. Once I entered the village on 18 March 2019, however, I first met Sama’s grandson Linga, the de-facto Sarpanch of that village, and then Sama’s son Joga, a man in his 70s. After hesitating a little, their family was kind enough to bring out Sama’s prized possessions, including the Albert Medal, a silver armlet with his name inscribed on it, a silver belt and even the charter giving him 45 acres of land,” he says.

Linga told him everything about Sama’s story in Madia and Telugu and even took him to the site of the tiger attack following an arduous trek through the dry deciduous forests. Through Linga’s stories, Amit found out how indebted George felt towards Sama. Such was the relationship they developed that George established a forest village adjacent to Mudewahi, named it after himself, planted a small reserve forest and set up systems of irrigation in those parts.

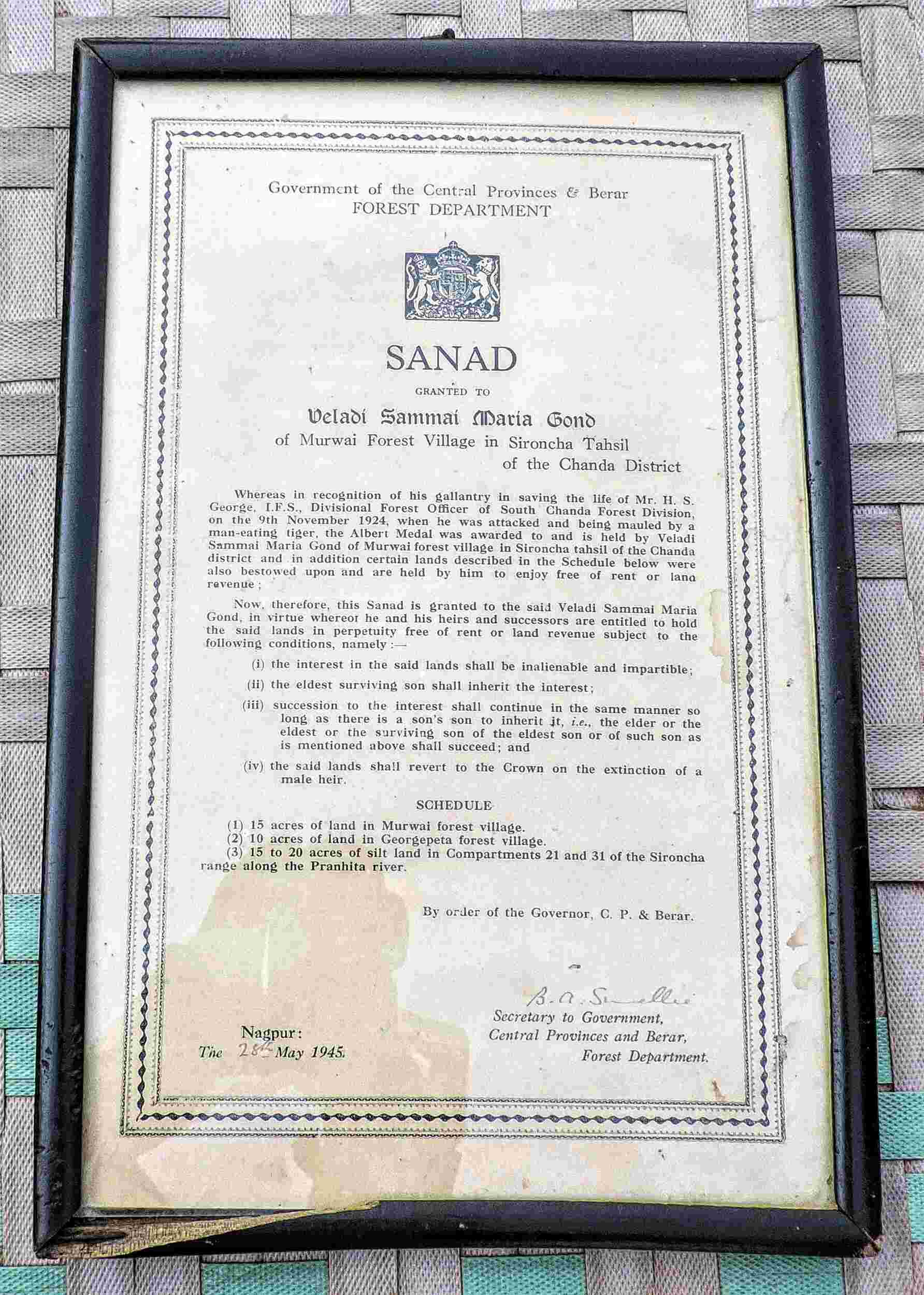

“Moreover, Geroge knew that Sama was landless and didn’t have any assets to fall back upon since he had left his home village 100 km away after a quarrel with his brothers. So, he reached out to his contacts at the Forest Department and requested them to financially reward him as well, and he was soon given a cart with a pair of bullocks, a house and issued a Sanad (charter) granting him 45 acres of land 20 years later in 1945,” notes Amit.

However, the irony was that the aboriginal Madia Gonds were hunters and not farmers, and Sama never took possession of that land. HS George retired as the Chief Conservator of Forest for the entire Central Provinces in 1947 and went back to Britain. He died in 1967, while Sama passed away in 1968.

Nearly 40 years later, Sama’s descendants reached out to the authorities and requested them for that land. Since the authorities had no idea about Sama or the incident and their records showed that the piece of land hadn’t been assigned, they refused.

“His descendants are still fighting that battle. So, I contacted the DFO of that area, RFO, and a local social worker, who are helping the family regain that land. This process is still undergoing,” informs Amit.

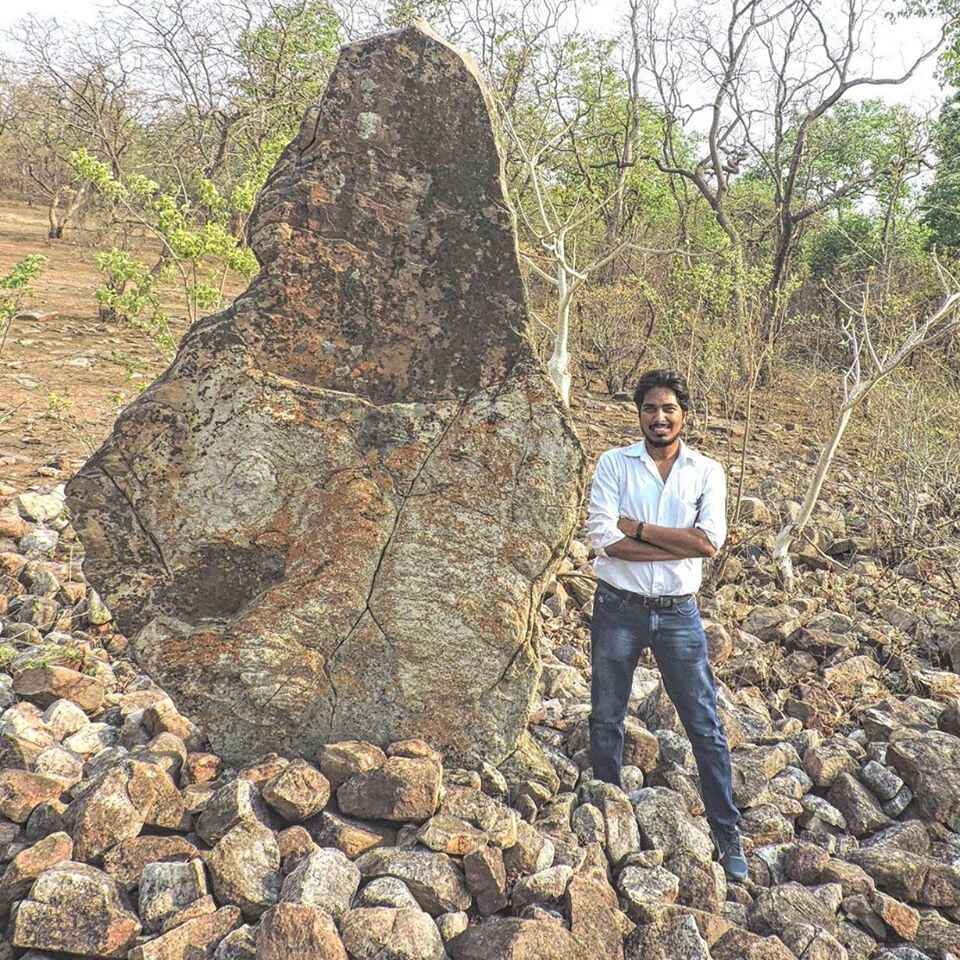

Meanwhile, in remembrance, Sama’s family erected a memorial stone (Menhir), where a large bamboo bottle, symbolising his love for toddy, hangs in his honour. They regularly pay tribute to him on every festival and as per local customs, offer the first grains of their harvest every year to the memorial stone.

Respecting Tribal Culture & Heritage

Amit has always held a deep fascination for the Vidarbha region’s rich history, natural resources, wild forests and vibrant culture. But what he notices is also a deep divide between Vidarbha and the modern cities of Western Maharashtra.

“They always look down upon people from the region, particularly adivasis living in the forests of Gondwana calling them ‘jhadipatti’ or ‘people from the jungles’. They are regarded as backward, and the region and culture receives little respect. In their imagination, Vidarbha extends just to the city of Nagpur. But when I was posted in Chandrapur, I found a region with a unique topography, beautiful inhabitants and a fascinating history that include the presence of pre-historic sites, dinosaur fossils, medieval forts, ancient temples and a unique proliferation of tribal culture. Their ‘backwardness’ so to speak was because they had not realised the strength of their own heritage. There were barely any records of the Gond dynasty that lorded over these forested hills for five centuries,” he says.

To uplift these communities and battle the scourge of Naxalism, he believes, the Maharashtra government must give the Madia Gond community not just guardianship of these prehistoric sites, through which they can earn some tourism revenue, but also include stories of Gond heroes like Sama Veladi in their state textbooks as well.

“I cannot emphasise this any further. Their stories must be told,” he says.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167