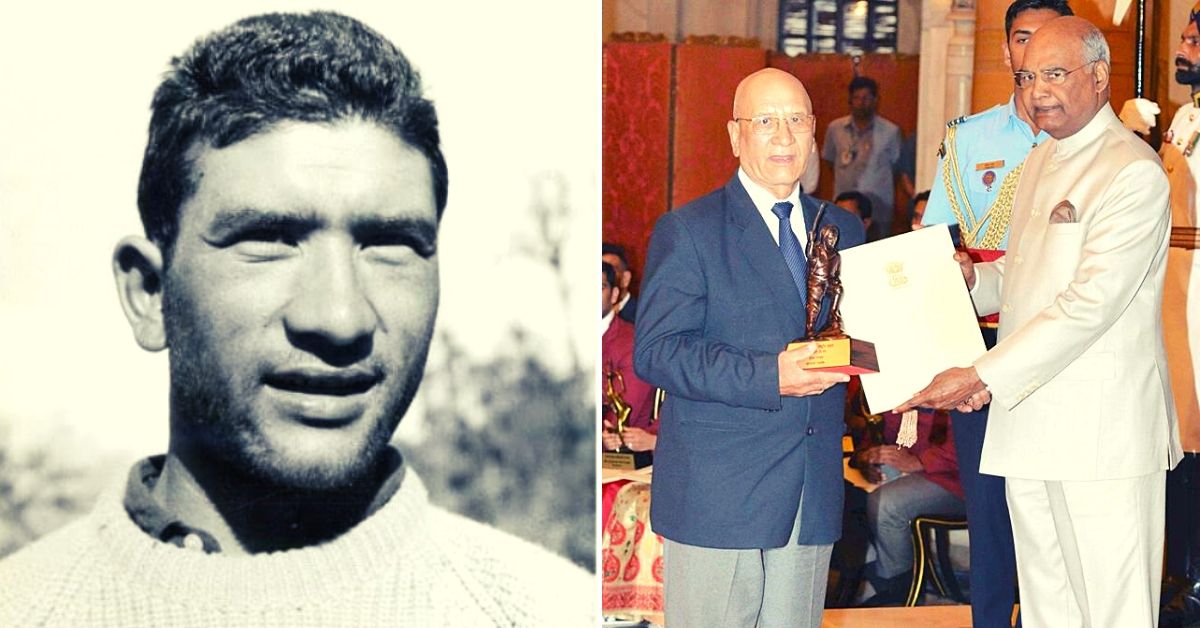

By 23, This Ladakhi Had Climbed the Everest, Won Padma Shri & Battled The Chinese

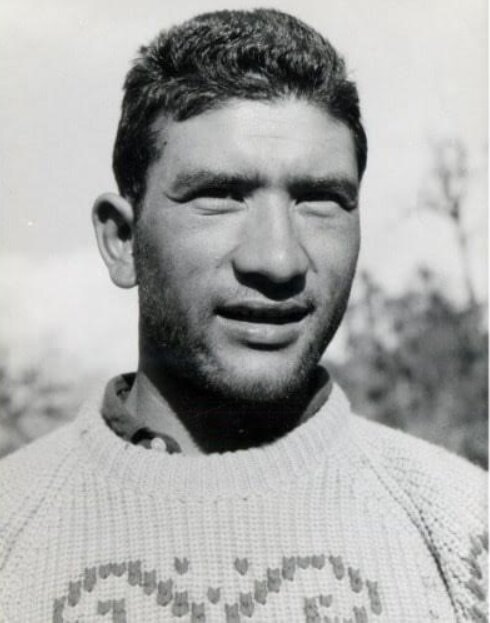

“We had climbed Everest. What did I feel? Nothing at all. There was no elation, no sense of overpowering; I was exhausted and all I wanted to do was to sleep but that did not seem possible…We had much to be thankful, for we were still alive and safe,” recalls Sonam Wangyal, the youngest member of the first successful Indian expedition to Mt Everest.

Sonam Wangyal was barely 12 years old when Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary scaled Mount Everest in May 1953, but clearly remembers the day he found out about their achievement.

“Headmaster Eliezer Joldan delivered the news during the daily prayers in school. He also told us that Mount Everest was so tall that it literally touches the sky. As children, we thought if the mountain is this tall, we could probably see it from our homes. We tried for a few months, but to no avail,” says Wangyal with a hint of laughter to The Better India.

Twelve years later, at 12.30 pm on 22 May 1965, Wangyal, then a 23-year-old havaldar serving in the Indo-Tibetan Border Force (ITBF) from the Oldan household in Tukcha village, Leh, reached the summit of Mount Everest.

“Lying in my sleeping bag, I tried to think of the day which had passed. We had climbed [the] Everest. What did I feel? Nothing at all. There was no elation, no sense of overpowering; I was exhausted and all I wanted to do was to sleep but that did not seem possible. Sonam Gyatso (his partner during the final ascent) was in a bad way. He needed [medical] attention. Both my lilo and its pillow were punctured. Sleep, thus, in spite of oxygen, was neither deep nor restful. We had much to be thankful [for], for we were still alive and safe,” reads an entry in his diary.

As he was the youngest member of the first successful Indian expedition to the world’s highest mountain, awards naturally followed suit.

But the fact is that while winning the Arjuna Award and Padma Shri may have strengthened his pride, for the most part, he was just thankful to be alive. Moreover, reaching atop Everest was a culmination of what had already been a remarkable life.

An Ordinary Life Turned Extraordinary

Wangyal was born to Sonam Stobdan, a numberdar, and Tsewang Dolma, a homemaker, on 8 January 1942. Tragically, by the age of eight, his mother had passed away, while his father mostly remained away from home at work. Although both his parents were illiterate, they ensured he got an education.

After his matriculation, he was first appointed as a primary school teacher in Basgo village on 31 March 1957. Exactly a year later, however, he quit his job as a school teacher to become a clerk in the local forest department. A year later, he quit this job as well.

“Since my mother had passed away, my father wasn’t around most of the time because of his work and an elder brother was serving in the Ladakh Scouts, I had no one at home. I was worried about my future. With no prospects in sight, I thought I would either commit suicide, run away from home or enlist myself in the armed forces,” recalls Wangyal.

By sheer accident, Wangyal would end up eventually enlisting with the Indo-Tibetan Border Force (ITBF).

“ITBF had been performing the task of border guarding force besides working as an Intelligence Agency until [the] early sixties when Indian Army and ITBP took over the role of border protection,” notes this special issue of the Indian Police Journal published by the Bureau of Police Research and Development.

Within months, he was posted out at the Chang Chenmo river valley located near the disputed India-China border. Under the command of Deputy Superintendent SP Tyagi, a senior officer serving in the Central Reserve Police (which we know today as CRPF) and Karam Singh, a Deputy Central Intelligence Officer (DCIO) with the ITBF, he was involved in a brutal encounter with Chinese forces on 21 October 1959 at Hot Springs (locally known as Kyam).

Enemy forces had earlier engaged in unauthorized capture of Indian Territory. On 19 October, Dy SP SP Tyagi, along with Constable Sonam Wangyal, K Dechen and Chering Norbu Tomtom, left on a recce. They reached the top of a mountain approximately 16,000 ft high from where the Ngagzoo Thang area of the Chang Chenmo riverside was visible.

But they did not notice any Chinese movement there. On the following day, DCIO Karam Singh dispatched 6 personnel along with Coolie Tsetan, a resident of Chushul, who served as a guide.

Only 4 returned to Camp, so DCIO Karam Singh and SP Tyagi decided to send a search party and a young Sonam Wangyal was a member of the team. Unfortunately, until 10 pm they couldn’t find any of the missing men.

On 21 October, what followed was a brutal firefight that led to the death of 10 Central Reserve Police personnel and the capture of 10 more by the Chinese.

This is why, every year on 21 October, police departments nationwide celebrate Police Commemoration Day in memory of those who died battling a heavily armed Chinese regiment in freezing conditions and high altitudes.

Climbing His First Peak

The following year, Wangyal got his first opportunity to climb.

Drafted into a five-person team to climb ‘Khang Lhajal’ or Stok Kangri—a 6,153 metre-peak overlooking Leh—he knew barely anything about the basics of mountaineering. Leading this expedition was his namesake Sonam Wangyal from the ITBF and father of future Mahavir Chakra recipient Sonam Wangchuk, followed by P Wangdan, Captain Ghosh of the Indian Army, and fellow ITBF constable Sonam Chogdan.

After some basic training, Wangyal was put in the middle of the expedition team during the climb. Before their attempt, many British expeditions had attempted to scale the peak but were unsuccessful. Since no one in his team had extensive experience in mountain climbing, they used all their muscle power to climb towards the summit.

“However, before we knew it, the sun had gone down, and it was dark. Instead of descending in the dark on all fours, we decided to spend the night there. Stuck close to the top, we had to spend the night of 28 October. We didn’t even have proper clothes or boots. Through the night, we had to massage, rub and slap each other to keep our blood circulation going. By 3 am, both the leader of the expedition and deputy leader began telling us that if ‘either of us dies, please tell our families so and so’. My response was ‘If both of you are going to die, then I am definitely going to die’,” he recalls.

Somehow, all of them managed to stay alive. Upon reaching Leh, he was given a cash award of Rs 50 for being the youngest climber on the team. He soon rejoined his unit and was involved in a series of encounters against the Chinese forces, where he lost more of his compatriots.

Two years later, he was relieved of his duties on the border after receiving an order from Delhi to climb the Hathi Parbat. In June 1963, he made the ascent up Hathi Parbat peak, which was soon followed by 22 similar successes.

But his life would change for good thanks to a letter he received in September 1964. At the time, he was posted as a Havaldar in the remote Hundar village of Nubra Valley.

Mount Everest Beckons

“I received a letter from the Joint Secretary, Ministry of Defence, confirming my selection for a pre-Everest expedition in Darjeeling scaling the Rathong peak, which doubled up as a selection test for the Everest expedition,” he recalls.

He was in his element at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in Darjeeling and would go on to scale the Rathong peak confirming his spot in the expedition. After returning to Ladakh for two months of high altitude training, he was back in Delhi in February 1965 to join the team led by Mohan Singh Kohli and his deputy Major Narendra Kumar.

Before the expedition, which was sponsored by the Indian Mountaineering Foundation, BN Mullick, the then chief of the Intelligence Bureau (IB), spoke to Wangyal about the two unsuccessful Indian Army expeditions to Mount Everest. The first was in 1960, and the second in 1962. He wished him luck with the hope that this team would fulfil his 10-year dream of seeing an Indian expedition team atop the mighty mountain.

After a sendoff from then Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, the team set off for the border at Jaynagar in Bihar. From Jaynagar, the team trekked for a month before reaching the Everest base camp.

As the youngest and junior-most ranked member, he did feel a little intimidated around more experienced members. But he found solace working with Sherpas, who shared his faith, culture and even eating habits. Ferrying loads with them, he was involved in the process of opening up the route for the team till 26,000 feet.

He would reach this mark on three different occasions, but turned away the other two times because of heavy snowfall and winds gusting at speeds of 130 kmph. By 19 April, the team had established camps on the mountainside and descended to basecamp before making their attempt at scaling the summit.

While AS Cheema and Nawang Gombu, who had previously scaled the peak with Hillary and Norgay, would go ahead as the first of the summit parties, Wangyal was teamed up with veteran mountaineer Sonam Gyatso from Sikkim, who had scaled Cho Oyu in 1958 and made the first ascent of Annapurna III in 1961, as part of the second summit party. Gyatso was 42 at the time and the oldest among the climbers.

By 27 April, the first summit party had gathered at South Col, hoping to make that final push up the summit. However, bad weather laid waste to all their plans and had no choice but to retreat and recuperate back at base camp. It was only by 14 May when the weather cleared up. But it was getting very late in the season, and the number of opportunities to scale the peak had diminished significantly. It was now or never for the Indian team. By 19 May, both Cheema and Gombu set up a summit camp above South Col, before reaching atop Mount Everest on the following day.

“On 21 May, when Gyatso and I had reached Camp VI, our tents had flown away. Faced with high winds and heavy snowfall, we didn’t know where we would stay for the night and thought that we might have to go back down. Miraculously, we found the damaged tents under the snow after a short search. The Sherpas with us did the remarkable job of fixing the damaged tents, giving us additional oxygen and climbing down. With just the two of us alone, Gyatso complained of something on his back,” recalls Wangyal.

Unfortunately, a part of Gyatso’s back had also been frostbitten. “Gyatso had put on some weight, and with an extended belly, his clothes may have come off his back at some point, leaving it exposed to icy winds. He was in a lot of pain, but I did everything I could through the night to save his life,” he recalls.

“Now, on 21 May, we waited anxiously for news of the two Sonams. All of us were worried. Gombu felt that the winds on the South-East Ride were not less than 150 kmph…We were more and more worried. Finally, at 3 pm, Wangyal came on the wireless…What a relief it was to hear from Wangyal. Gyatso and Wangyal had shown great grit and determination. They had gone to Camp VI in almost impossible weather conditions,” writes MS Kohli in his book ‘Nine Atop Everest: Spectacular Indian Ascent.

By the following morning, when they reached the Hillary Step, Gyatso’s oxygen had run out. Wangyal had to help refill it for him. At 12.30 pm on 22 May 1965, both reached the summit, where they spent 55 minutes. It was a very long stay.

“At the summit, I took out a ring my late mother had given me and pitched a small Indian flag along with it. But on our descent, when we reached Hillary Step, Gyatso realized that he had forgotten to place the idol of Lord Ganesh on the summit, which had been given to him by BN Mullick. So, I went solo to the summit once again and placed the idol there. It was my second climb to the peak in one hour which was another feat. We were supposed to descend to South Col, but because of Gyatso’s injury, we had to camp at 26,200 feet and spend the night, where he was once again screaming in agony over the frostbite. Somehow, we reached the base camp the following day,” he recalls.

Despite spending so much time at the summit and taking a lot of photos, they realized at basecamp that the camera roll had not been loaded properly. Imagine their frustration!

Nonetheless, scaling Everest changed Wangyal’s life forever. After winning multiple national awards, he went back to his unit, became an officer, spent years defending our borders, getting posted in different parts of the country and served as Principal of the Sonam Gyatso Mountaineering Institute, Sikkim for 14 years (1976-1990) training many to climb Mount Everest and Kanchenjunga before retiring from service on 31 January, 1998.

Retiring at the rank of Assistant Director, Wangyal made the absolute best of his remarkable life, which may have taken off accidentally, but leaves behind a legacy that is hard to match.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167