This Architect’s Low-Cost Algae Wall Filters Polluted Waters With No Chemicals!

Designed for artisans, this system is compact in size, allowing artisans in small industries to construct and maintain the 'wall' by themselves.

Two years ago, when Shneel Malik was on a trip to explore India, she discovered the seed of innovation. It started when she came across various small-scale artists, jewellery workers and textile dyers. Though she was fascinated with their work, Shneel noticed that the outcome of their art was not just a thing of beauty, but also of danger and destruction. The process of producing textiles often released toxic residues like cadmium, arsenic and lead into the waters in the area, not only polluting the water, air and soil, but, also jeopardising the life of the artisan community.

Have a green thumb? Explore our collection of all-organic seeds and start your own farm in your garden, terrace or even a balcony. Check out these here.

But, the answer to this problem was not to eliminate their skill and means of livelihood, but to focus on just the putrid waste-water. Inspired, Shneel, an architect and currently a PhD candidate at the Bio-ID Lab under the Bartlett School of Architecture, London, along with a diverse team of experts, created INDUS—a modular bioreactor wall system capable of cleaning water polluted with dyes and chemicals.

“Indus comes out from the research journey over the last few years where I have been investigating the large scale fabrication of biocompatible membranes for applications within our environment. In 2017, as part of an EPSRC Global Challenges Research Fund Project, I, along with Dr Brenda Parker (Biochemical Engineer, UCL) and Dr Laura Stoffels (Biologist, UCL), travelled to India to meet NGOs and conduct site studies to better understand the existing scenario within the artisanal communities; identifying potential design opportunities,” Shneel informs, in conversation with The Better India.

Brenda, a biochemical engineer and Shneel’s Ph.D supervisor, has been conducting research using microalgae to treat wastewater. And Shneel’s research on designing biological scaffolds for the photosynthetic activity of microalgae, complimented her research.

“Neither the artisans have any space available for Westernised high-tech water treatment solutions, nor do they have the economic capacity to get additional support. Therefore, we started to design a system which is both spatially compatible, but more importantly, can be constructed and maintained by the artisans themselves,” says Shneel.

Based on the principle of bioremediation, Shneel, Brenda, and Professor Marcos Cruz have designed this structure which is layered with microalgae and seaweed-based hydrogel. It cleans heavy materials from waste-water, everytime it passes through it. And, all of this has been done in a cost-effective way.

Along with the help and support of NGOs like Pure Earth and CEE that focus on battling pollution, the team conducted on-ground surveys of multiple sites in Kolkata (bangle-makers) and Panipat (textile dyers), among others.

“These site visits made us better understand the site and context-specific constraints and challenges in wastewater treatment,” she told TBI.

But, how exactly, does the system work?

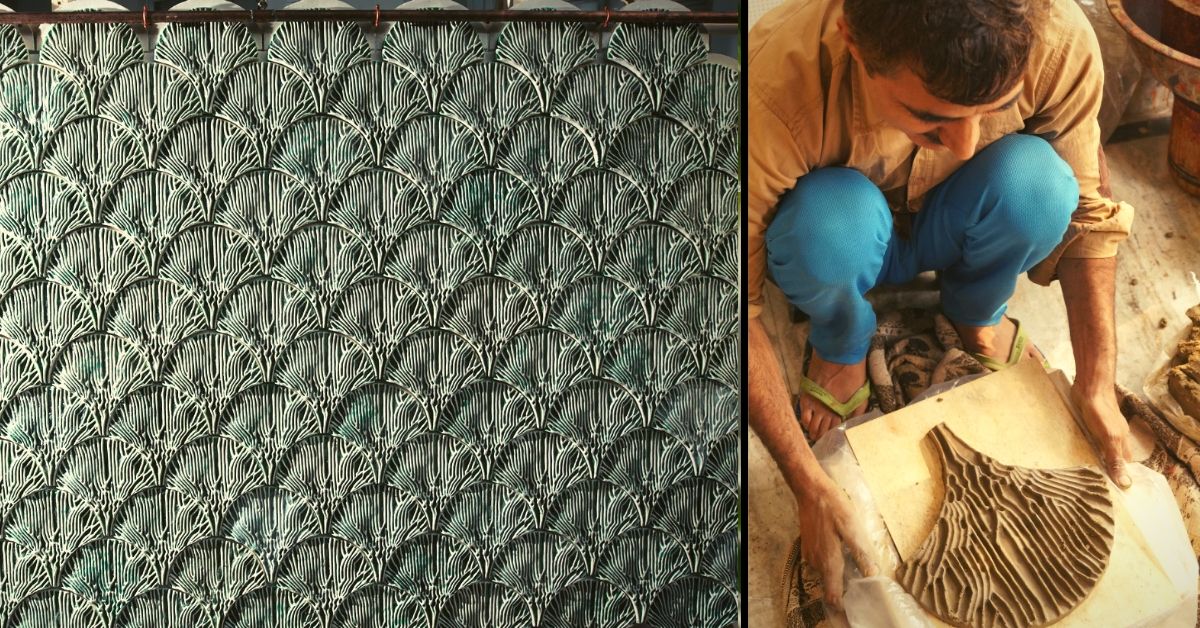

The tile-based modular bioreactor wall system, much like Shneel’s previous projects, is an extension of nature itself, and is designed to clean polluted water through an assembly of tiles. Inspired by the complex architecture of a leaf, the tiles have vein-like channels carved inside containing algae prepared in a seaweed-based hydrogel which isolates the pollutants every time the water flows through the tile.

After some time, thanks to algae’s natural bioremediation capabilities, the hydrogel becomes saturated with pollutants like cadmium. It can then be processed to recover heavy metals safely, thus eventually filtering water for reuse for the purpose of manufacturing textile. One can pass the waste-water multiple times through the tile, depending on its toxicity.

While on the one hand, the Indus project plans to tackle water and soil pollution caused by textile dyes in a cost-effective and technically-accessible manner, it also hopes to empower the communities in the process.

It aims to enable panchayats and rural community of artisans to sustainably regenerate water within their manufacturing process for reuse, as these tiles, according to the makers, can be produced locally by the communities using traditional clay-making methods.

“What was extremely enlightening was the fact that these communities are becoming more and more aware of the urgency of fixing the manufacturing processes. They seemed ready to take that extra effort in making their surroundings livable. Therefore, a system like Indus is designed to empower the community, making them capable of adopting new forms of daily practices,” she adds.

After a few years of research, the team participated in an international research program and competition called the Water Futures Design Challenge by A/D/O, Mini, New York. The competition invited interdisciplinary designers from across the globe to design and develop potential solutions to tackle the increasing water crisis.

Indus, which is developed as part of a research lab called Bio-ID (Bio – Integrated Design) at the University College London, eventually went on to win the category award under the future systems and infrastructure along with the audience vote earlier this year.

“I then travelled back to India to work with the ceramic artists in Khurja (ceramic capital of India) to make the very first ceramic prototypes of the tiles – which were then exhibited in New York,” adds Shneel.

Their Indus project is currently in the Research and Development stage. The next immediate step is to test a fully-functional prototype in-situ in the UK where they can refine the set-up for efficient performance. Following this they are hoping to do a pilot-test on site (in the courtyard of a textile dyeing unit in India) within the next 1 year.

“I imagine a system like Indus to revolutionise how we interact with our natural resources. We are making high-tech engineering techniques available in a rather low-tech manner, which will allow these communities to leapfrog into the future, while setting trends and new forms of daily practices for our next generation,” concludes Shneel, who envisions to make Indus available to local communities in every corner of India, in the next coming years.

A venture with an extraordinary promise, we extend our best wishes to Shneel and her team of innovators!

Also Read: Meet the Architect Behind India’s First Ever 5-Star SVAGRIHA Green Home

(Edited by Saiqua Sultan)

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167