India May Not Have Been a Nuclear Power Had It Not Been For This Unsung Botanist!

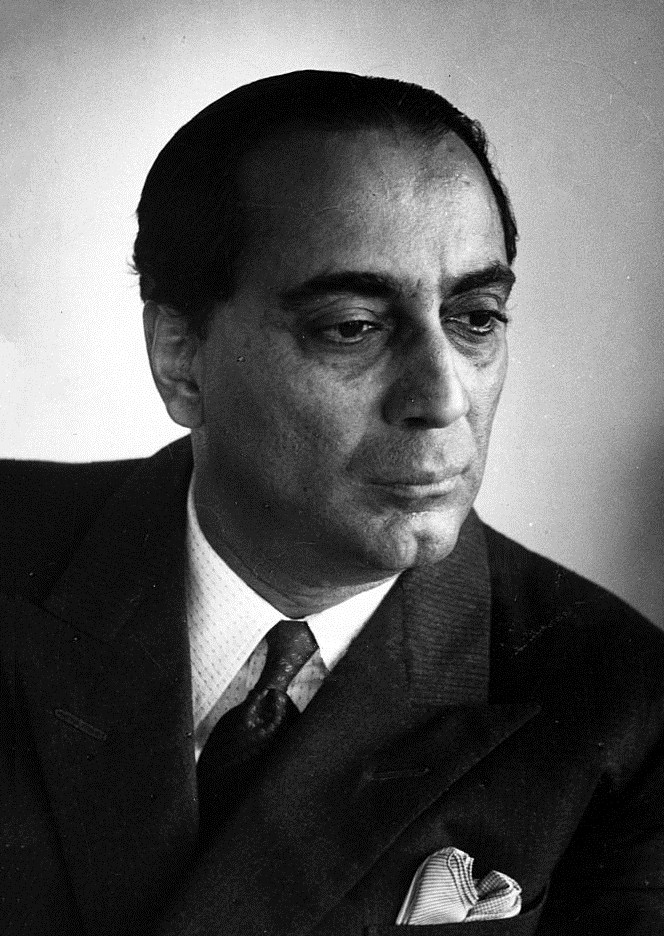

An institution builder in the truest of sense, SP Agharkar was a man ahead of his times. But despite his immense contribution to Indian science, few know about him.

Without the contributions of Professor Shankar Puroshottam Agharkar, one of India’s greatest botanists, it’s unlikely that India would have developed its nuclear programme as soon as it did under the guidance of Dr Homi Jehangir Bhabha in the years following Independence.

It was thanks to Professor SP Agharkar’s efforts that young scientists like Homi J Bhabha earned an 1851 Research Fellowship, a scheme conducted by the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 to annually award to “young scientists or engineers of exceptional promise.”

Although several members of the Indian royalty and business community helped establish this scholarship scheme, no Indian students were selected until Agharkar took up the matter and brought a successful resolution to the problem. In 1936, Bhabha was one of the first Indian recipients of Senior Studentship of the 1851 Exhibition, which allowed him to extend his work at the famous Cambridge University until the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

“That year he visited the Wills Physical Laboratory at Bristol and worked with a senior scientist, Walter Heitler, on the problem of cosmic ray showers, developing the now-famous Bhabha-Heitler cascade theory,” says this research paper. His collaboration with Heitler found significant coverage in the famous science journal Nature and even in the Proceedings of Royal Society, but more importantly had significant ramifications in the subsequent development of atomic energy.

Aside from helping promising Indian scientists with scholarships, Agharkar played an important role in laying the foundations for premier Indian scientific institutions like the Indian National Science Academy, Indian Science Congress and last but not the least, the Maharashtra Association for Cultivation of Sciences (MACS) in Pune, which is today known Agharkar Research Institute.

Born in November 1884 in Malvan, a remote village of the Ratnagiri district, Maharashtra, Agharkar grew up with a father working for the Public Works Departments. His constant transfers meant that Agharkar could never reside in one place for too long.

He picked up several languages along the way, and his determination to acquire knowledge of the sciences and pursue research at all costs proved handy in schools where sometimes the teachers wouldn’t show up. In one particular school, Agharkar took up the task of teaching his classmates because the teachers there weren’t committed to their task.

After completing high school from Dharwar, he proceeded to Elphinstone College in Mumbai, studying botany alongside zoology and botany as minor subjects. After completing his Masters from Elphinstone College in 1909, he joined the same institution as a lecturer in the biology department. This is where his love for research really came to fruition.

On days off or in between teaching assignments, he would venture towards the biodiversity-rich Western Ghats, exploring different species of plants and animals. It was during one such trip when he came across a species of freshwater jellyfish, which was until then only known to be found in Africa. The scientific journal Nature published his findings in 1912. Thrilled by this discovery, Agharkar stepped up his research work. Assistance came from a certain Dr Annadale, the Superintendent of the Indian Museum in Kolkata, who helped Agharkar collect, preserve and conduct microscopic examinations of animal and plant specimens.

“Agharkar’s name has been immortalised in the names of many species of plants and animals he discovered. These include amongst others, the net weined midges Philorus bioni Agharkar, not previously reported from India; two flowering plants (Dioscorea agharkarii and Musa agharkarii); one fungus (Mitrula agharkarii); and one centipede (Cryptorbyptops agharkarii).

Agharkar also studied the flora of Nepal and the Western Ghats and was a scholar on gymnosperms and angiosperms,” says this Vigyan Prasar tribute to the scientist.

His passion for research took him to Germany just before the breakout of World War I in 1914. Despite making most of his time in Germany, there were some serious interruptions with the outbreak of the Great War, during which he was imprisoned for three years.

Nonetheless, by 1919, he obtained his PhD from Berlin University, and during his time there visited various botanical gardens across Europe and the British Isles, collected rare plans from the continent’s mountains and presented this unique collection to Calcutta University on his return in 1920.

For his phenomenal research work, he was offered a professorship in Calcutta University on the recommendation of Dr CV Raman, another Indian scientific legend. It was a recommendation that would pay rich dividends to the University as the Botany Department under Professor Agharkar became one of the best plant sciences research institutions in the world.

Subsequently, he would go onto serve the nation’s scientific community as the Secretary of the Indian Science Congress Association for decades. During his tenure, Agharkar pushed for the inclusion of Indian science students for the prestigious 1851 Research Fellowship, of which Homi Bhabha was a beneficiary. Until 1931, the scholarship was purely restricted to British nationals, but Agharkar fought to change it. He even stopped the British from transferring rare plant specimens stored at the National Herbarium in Shibpur, Kolkata to the Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew, London.

Protecting the research of Indian botanists, today institutions like the Botanical Survey of India have an extensive collection of herbaria thanks to Agharkar’s efforts.

Eventually, in 1946 he quit his position at Calcutta University but soon after took up the job of teaching post-graduates at Bombay University. That’s when the Indian Law Society in Pune reached to Agharkar with the hope of setting up an institute of scientific research and promoting it in the city. The same year MACS came into existence with Agharkar as Founder-Director, and Head of the Botany Department. Until 1966, MACS conducted its operations in the basement of the ILS Law College before moving the campus to a five-acre plot.

Also Read: 10 Things You Must Know about Homi Bhabha – Pioneer of Nuclear Program in India

The initial years were very hard, especially with concerns surrounding the lack of funds. For years, teachers and staff members there worked for free and voluntary basis, and Agharkar spent a lot of his own money. He even rejected the offer of installing a fan in his office, arguing at the time that it was a luxury. Nonetheless with sheer determination, drive and love for research, he turned MACS into an institution of scientific inquiry oozing with excellence.

The following two decades, however, would prove to be very hard after he was diagnosed with cancer, for which he had to undergo surgery in 1956. Four years later, he announced his retirement from the institute and on September 2, 1960, he passed away.

Nearly 32 years later, the country paid the ultimate tribute to the man when they renamed MACS and changed it to the Agharkar Research Institute under the tenure of one of India’s most recognised scientists, Professor CNR Rao.

“Today, ARI has over 60 ongoing projects and several international collaborations. The main themes of research here span six areas — biodiversity and paleobiology, bioenergy, bioprospecting, development biology, genetics and plant breeding and nanobioscience,” reports The Indian Express.

None of that would have been possible without the work of Professor SP Agharkar.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167