Martyred at 26, This Naga Freedom Fighter Has a Story Every Indian Should Know

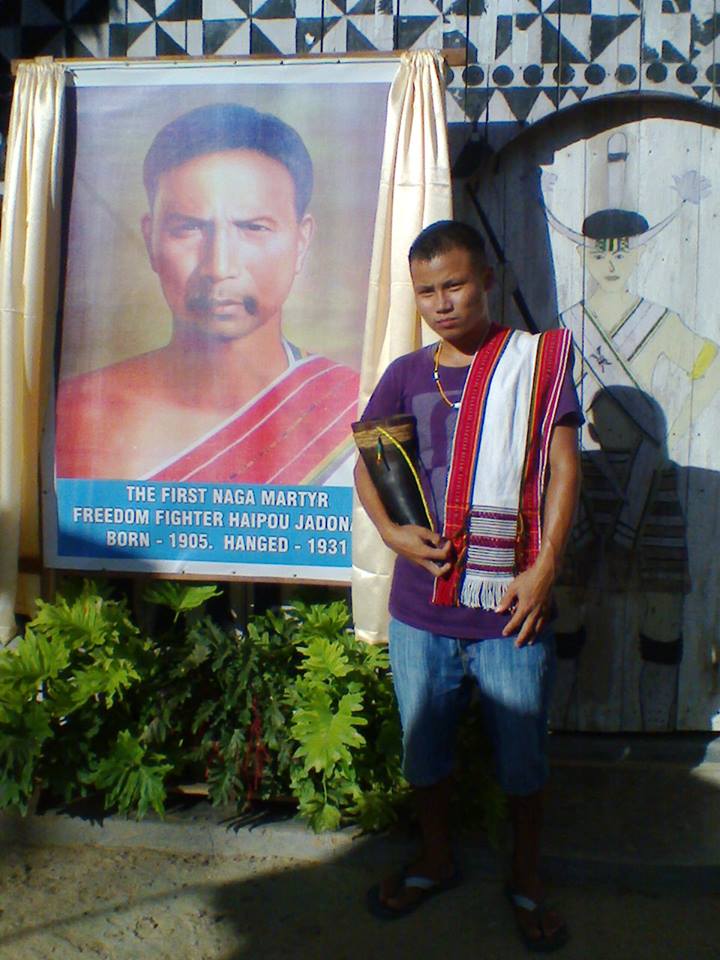

A man who built an army of 500 to take on the British, Haipou Jadonang has been largely overlooked by writers and historians. It's time this changed. #ForgottenHeroes #IndianIndependence

To honour this nation’s Independence Day, we bring you the fascinating stories of #ForgottenHeroes of #IndianIndependence that were lost among the pages of history.

Freedom fighters fundamentally stand on two pillars—their spiritual and political convictions. Without one, the other does not stand. Subtract faith from Mahatma Gandhi, and there is very little one would understand about his anti-colonial struggle.

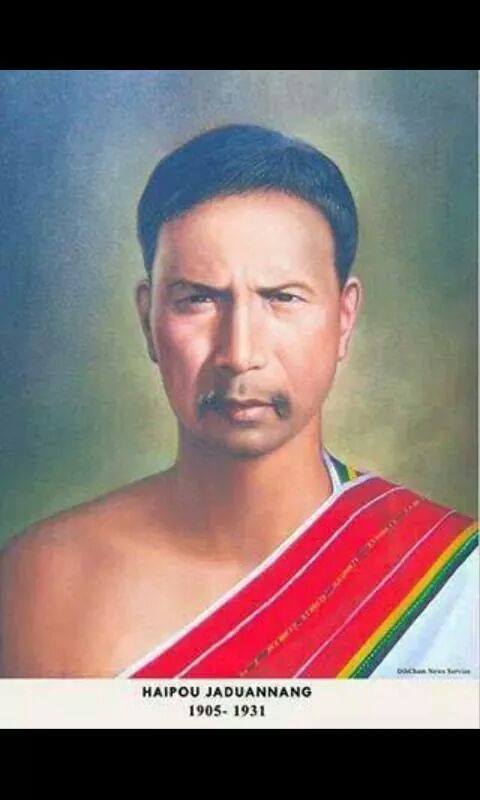

Haipou Jadonang, the Rongmei Naga leader from present-day Manipur, was a spiritual leader, social reformist, and political leader who sought to emancipate the Naga people from the clutches of British colonial role during the early decades of the 20th century.

Very little is known about him in our school textbooks because he fought in a corner of the country that remains outside the imagination of mainstream India. However, thanks to extensive research by scholars from the Northeast, his story remains up for public consumption.

Born somewhere around 1905 (the exact date of his birth is unknown) in Kambiron village of present-day Tamenglong district in Manipur to a poor peasant family from the Malangmei clan of the Rongmei Naga tribe, Jadonang was the youngest of three sons.

Jadonang was seen as a spiritual figure even early in life, garnering the attention of neighbouring villages, especially folks from the Zeliangrong tribal community—one of the significant indigenous Naga communities living in the tri-junction of Assam, Manipur and Nagaland—under which the Rongmei Nagas fell.

By the age of 10, he would pray for long hours, visit places like the Bhuvan Cave (near Silchar, Assam) and Zeilad Lake (Manipur) – sites of significant religious importance for the Nagas – and make predictions, besides using local herbs and medicines as healing agents for those who came to him with various illnesses.

Growing up, however, what Jadonang saw was the rising proliferation of Christianity. He felt this was an instrument of British imperialism. In the areas in and around present-day Tamelong district, the British had asserted control by then, posting officials to oversee administration.

According to Jadonang, the conversion efforts of British missionaries in the region posed a serious threat to indigenous Naga faith, customs and society. Of course, there were the economic costs that British imperialism had also imposed on the Nagas with high taxes, the introduction of colonial law and an oppressive porter system.

Many Zeliangrong families converted to Christianity purely out of necessity— hoping that appeasement of the British would lower their economic burdens.

Towards his late teens and early adulthood, Jadonang’s ideas about the revival of indigenous Naga culture, the political struggle against the British and social change began to take shape.

Also Read: This Unsung Kerala Scholar Was The Architect of the Quit India Movement in Malabar!

At this juncture, it is imperative to contextualise Jadonang’s struggle with a growing pan-Naga consciousness among the major Naga tribes against colonial rule. A major turning point in the Naga struggle against the British, which subsequently translated into the formation of the Naga National Council and the modern-day National Socialist Council of Nagaland, was World War I.

Many Nagas across different tribes enlisted into the British Indian Army, serving as members of the labour corps in major theatres of World War I, particularly the Mesopotamia region and France.

Besides exposing them to a world outside their own insulated tribal communities and struggles against colonialism in other parts, it also resulted in the formation of the Naga Club.

“The Naga club, supported by British administrators, was subsequently formed in 1919, after the return of several Nagas who served in the labour corps in France during WWI. This was the first sign of pan-Naga nationalism as different Naga ‘tribes’ came together abroad thus reifying their common solidarity in the midst of such strangeness,” writes noted Manipuri scholar Arkotong Longkumer, in his 2008 doctoral thesis for the University of Edinburgh.

According to some historians, Jadonang also served in the labour corps during World War I, leaving him exposed to such ideas which further strengthened his political convictions against colonial rule. Other scholars, however, dispute such claims, stating that there is no evidence to back them. Moreover, they believe Jadonang was too young to enlist at the time.

However, what’s beyond dispute is the socio-religious movement he started – called Heraka (translation: Pure), which he drew from his ancestral Naga practices.

Based on the worship of a supreme ‘creator’ Tingkao Ragwang’, Jadonang developed the Heraka religious reform movement, which others have called a cult. Although this particular deity was recognised among the Zeliangrong, it was just one of many gods.

“The religious reform of Jadonang in the traditional Zeliangrong society was a synthesis of Christian monotheism and Hindu idolatry and temple culture, rationalized and simplified form of religious worship, the social solidarity and unity among the Zeliangrong groups reviving their common origin, past and a political ideology of a kingdom which inspired political integration of the Zeliangrong people under a polity system, perhaps monarchy, thus making the Zeliangrong revolt for independence, anti-colonial struggle, identifying with the greater national struggle for India’s independence,” writes noted scholar on Naga history Gangmumei Kamei.

Besides the appropriation of ‘Tingkao Ragwang’, what Jadonang also did was getting rid of a multiplicity of customs, superstitious taboos, many rituals (gennas), including animal sacrifice except those dedicated to the ‘supreme’ deity. There was an emphasis on truth, love and respect for sentient beings. Even songs, hymns and prayers in praise of the supreme deity were encouraged.

“Different traditions of the village were made one common to all and the people were brought to stand in one platform of religion. Thus, through social renaissance, Jadonang put forward a new dimension and cultural vitality to the society which was suffering from rigidity, narrowness and compression for a long time,” this research paper notes.

Through these efforts, Jadonang was successful in organising society and acquiring public support, especially among the Zeliangrong, for his leadership. The ultimate aim, however, was to challenge British colonial rule, and the fight against proselytisation was one such aspect of the struggle.

Naturally, the Heraka movement faced stiff opposition from not just the British, but other Christian converts and members of other Naga tribal communities steeped in other traditional beliefs. However, what Jadonang was looking for was a secession of inter-village clashes, and communal tensions among various tribes, who must unite against a common enemy—the British.

In fact, according to some accounts, Jadonang had heard about Mahatma Gandhi’s Civil Disobedience Movement on the mainland and sought to express solidarity with it. In January 1927, according to the book ‘Evangelising the Nation: Religion and the Formation of Naga Political Identity’ by scholar John Thomas, Jadonang had arranged for a trip to Silchar with a dance troupe of 200 Naga boys and girls, to welcome Gandhi.

However, the British cancelled Gandhi’s visit, and the trip never materialised.

However, that didn’t put a stop to Jadonang’s call for political freedom – which he called ‘Makam Gwangdi’ (Kingdom of Nagas) or as the British called it, the ‘Naga Raj’. He even came up with a slogan ‘Makameirui Gwangtupuni’ (translation: ‘the Nagas would rule one day’). However, some scholars believe that ‘Makamei’ was a reference to the Zeliangrong people, in particular.

Also Read: Allah Bux Soomro: The Sindhi Premier Who Fought The British & The Two-Nation Theory!

Nonetheless, according to John Thomas, Jadonang travelled across lands inhabited by his fellow Zeliangrong people, and the Angami tribe, seeking support for his political leadership. He would travel on horseback, wearing British attire to move around undetected.

However, the British officials got wind of it in 1928, and SJ Duncan, who was then the Sub-Divisional Officer (SDO) appointed by the British, one day confronted Jadonang, asking him to dismount and remove a hat he was wearing.

The Naga freedom fighter refused, and so he was taken to Tamenglong, where the British interrogated him and ordered him to spend a week in jail.

Interestingly, Jadonang was arrested a week before the Naga Club, predominantly made up of members from the Angami community, submitted a memorandum before the visiting Simon Commission seeking independence for the Nagas. The timing helped bring the two sides closer together in their fight against the British.

Meanwhile, news of his arrest raised his popularity, and following his release, he started building an army, which he called ‘Riphen‘.

Comprising of 500 men and women at its zenith, the army was well-versed in military tactics, handling weaponry and conducting reconnaissance missions. It was also organised in civilian matters, assisting with farming, livestock grazing, and firewood collection, among other activities. Jadonang even composed songs singing praises of the struggle against the British, which his disciple Rani Gaidinlui (not ‘Rani’ then) imparted to his followers.

Meanwhile, Jadonang sent Riphen personnel to other Zeliagrong tribes, particularly those residing in the North Cachar, Naga Hills and Tamenglong Sub-Division in search of military alliances. Such was his popularity that some tribal communities offered taxes and tributes to him, while others rejected every offer for alliance coming their way outright.

With weapons, personnel and an innate understanding of the local terrain, Jadonang and his men were prepared.

Unfortunately, the British caught whispers of Jadonang’s strategy around January 1931. More than armed revolt, what annoyed the British was that he was now eating into their tax revenues.

In the following month February 19, the British arrested Jadonang at Lakhipur, while he was returning from his last pilgrimage to Bhuvan Hills with 600 other followers. He was charged with sedition after declaring ‘Naga Raj’.

Imprisoned in Imphal Jail, alongside hundreds of other followers, the British long interrogated him about the arms, ammunition and plans to overthrow the British, which he steadfastly refused.

Later that year, a British court found him guilty, sentencing him to death.

He was only 26 when he died at the hand of the British. However, his legacy was carried further by Rani Gaidinliu, his disciple, who was herself later incarcerated after many failed attempts, and released only after Independence.

Even though many in the mainland may have no inkling about Jadonang, his life is extensively celebrated in Manipur, especially among the state’s Naga community. Every year on August 29, members of the Naga community, especially the Zeliangrongs, celebrate his death anniversary with traditional songs, dance and festivities. In fact, the previous State government had built a bronze statue of Jadonang in Imphal, as a mark of respect for the “messiah king” of the Nagas.

It’s time we on the mainland acknowledged this freedom fighter’s contributions.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167