The Forgotten Tale of the Intriguing Bengali Spy Who Fell In Love With Tibet!

He was so captivated by Tibet that he called his house Lhasa Villa, on the edge of Darjeeling town. It still stands today, although in a dilapidated condition.

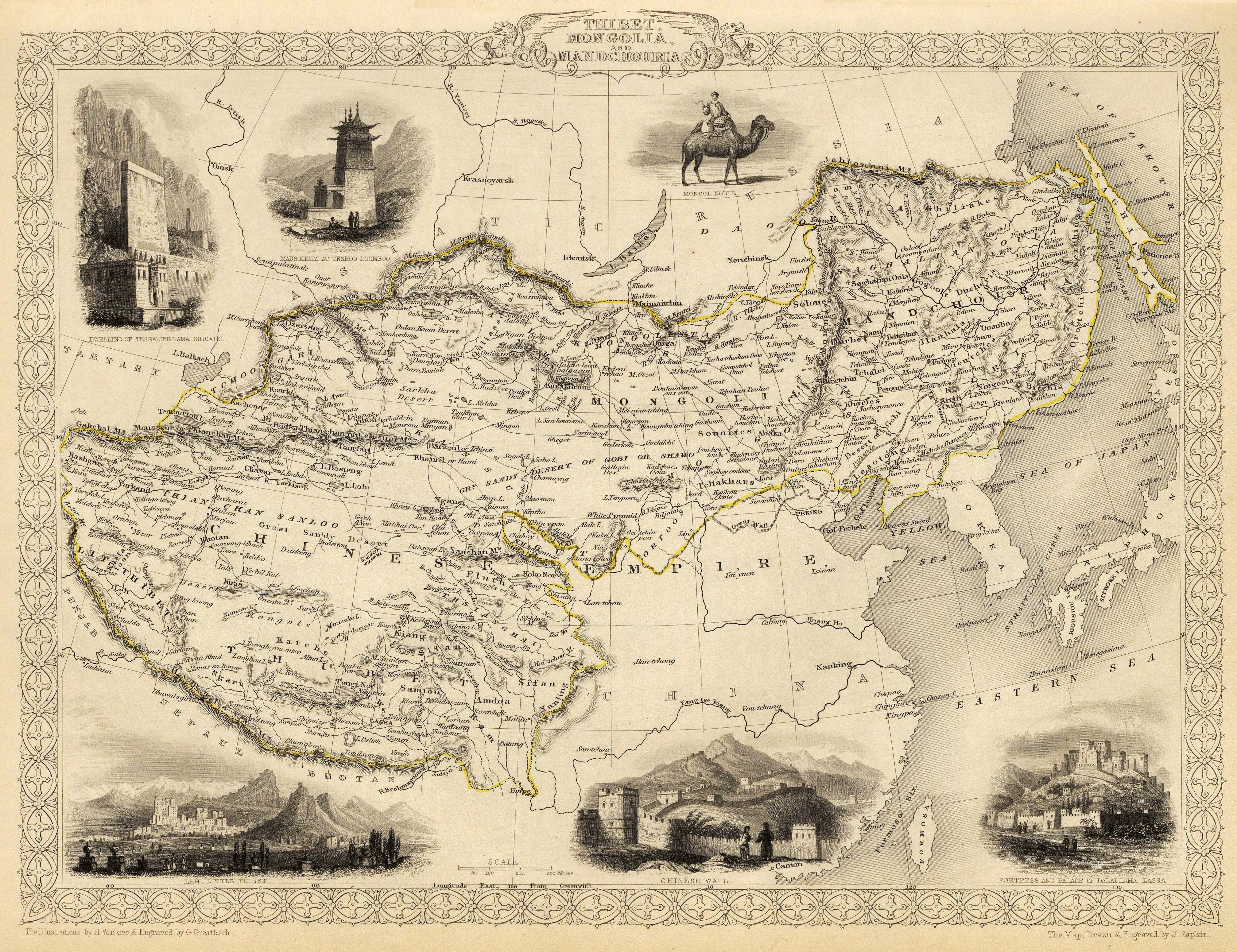

Central Asia in the 19th century was one of the theatres for the Great Game, a political and diplomatic confrontation that existed between the British and Russian Empire, extending to Afghanistan and South Asia. The confrontation arose from a fear within the British establishment that the Russian Empire would advance south to Central Asia, from where they would invade the British Empire in South Asia.

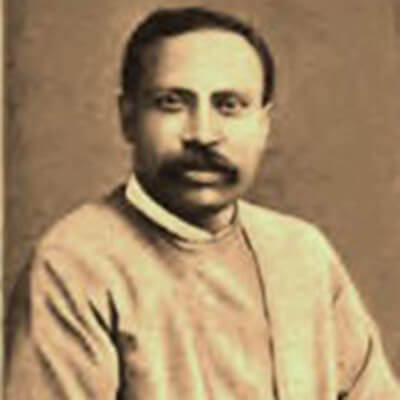

Many Indians, who were the subjects of the British Empire, were recruited for the Great Game. Among them was the scholar, spy and explorer extraordinaire, Sarat Chandra Das. This trained Bengali civil engineer twice ventured into Tibet on secret missions but came back a renowned Buddhist scholar who, among other works, ended up writing a 1000-page Tibetan-English dictionary.

Born to middle-class Bengali family in the Chittagong district of modern-day Bangladesh, Das enrolled into Calcutta’s prestigious Presidency College to study civil engineering.

Earning a reputation as a highly intelligent student, Sarat Chandra Das soon attracted the attention of his British teachers and was appointed as the headmaster of the Bhutia Boarding School in Darjeeling in 1874, before he had even received his degree.

According to Samanth Subramanian in the New York Times, it was around this time, that Das was struck by a bout of malaria.

If this had not happened, Sarat Chandra Das might have remained a civil engineer probably working in Calcutta. Instead, he was sent to Darjeeling. “This was how, at 25, Das came to run a school for spies, training agents to work along the India-Tibet border, growing so besotted with Tibet himself that he made two surreptitious journeys to the kingdom,” writes Subramanian.

The school recruited boys from the hills and taught them basic English and science, alongside the necessary skills to conduct cartographic surveys.

“In the European imagination, Tibet and its capital, Lhasa, were a fantasy, a fabled paradise of spirituality locked away from the world. In the late 1700s, Tibet began denying entry to Westerners, its government—under pressure from China—reluctant to play the games of imperial geopolitics. For Britain, Tibet’s inward turn was ill-timed, disrupting its plans to dominate Central Asia. In desperation, as the scholar Derek Waller found, the British cultivated ‘Pundits,’ Indians who had helped map the subcontinent and were now dispatched, in disguise, into Tibet, equipped with compasses and 100-bead rosaries to discreetly count their steps,” adds Subramanian.

Forget white-skinned Britishers it was nearly impossible for Indians from the plains to enter the kingdom perched on the roof of the world. However, trade between India and Tibet had been going on for centuries, dominated by Tibetans and hill tribes along the border. Besides them, the only other segment of the populace that had access to Tibet were Buddhist monks.

Finding an opening, the British sought to exploit it by sending spies into Tibet disguised as Buddhist monks, also known as Pundits.

“With sextants and theodolites in secret chambers of their boxes, compasses fitted on walking staffs, paper and hypsometers tucked in hollowed-out prayer wheels, and rosaries with one hundred beads instead of the sacred hundred and eight, they measured distances by keeping count of their paces and mapped swathes of the Tibetan territory,” writes Parimal Bhattacharya, who wrote the introduction to a collection of works by Chandra titled ‘Journey to Lhasa: The Diary of a Spy.’

Unlike other Pundits, who lacked formal education, Das was a scholar who had a deep yearning to visit Tibet and learn about its people and culture. After reading the works of English explorers who had visited the forbidden kingdom in the past, namely George Bogle, an East India Company officer, explorer Thomas Manning and botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, Das set off on his first sojourn to Tibet.

The British thought he was the perfect candidate for the task. While many Pundits died or were captured en route, Das survived two journeys to Tibet.

At the boarding school, along with Das, was Ugyen Gyatso, an assistant teacher and Buddhist monk affiliated with the famous Tashi Lhunpo monastery in Shigatse, eastern Tibet.

Das convinced Ugyen to procure a passport for him into Tibet under the guise of a theology student eager to learn Buddhism. Speaking to a high-ranking Buddhist monk at the monastery, Ugyen proposed that Das could teach him Hindi in return. With confirmation for a passport into Tibet, British officials granted him indefinite leave and gave him a crash course in espionage.

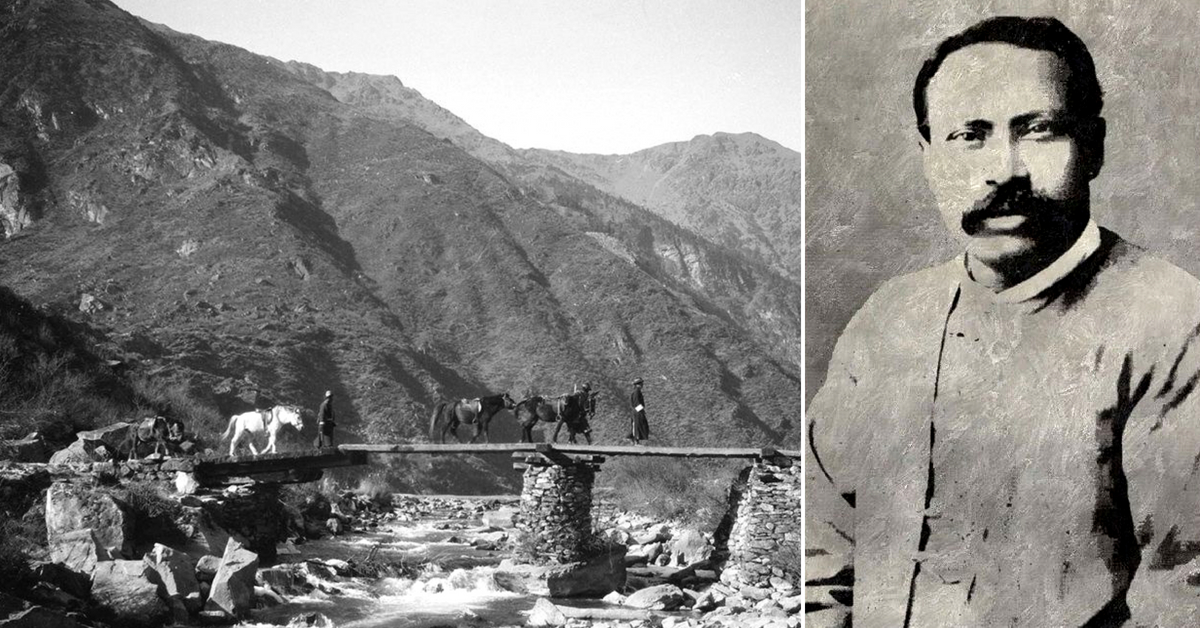

Das visited Tibet on two separate occasions—first in 1879 for a brief four-month stay, and subsequently in 1881 for fourteen months. He even followed the route laid down by Hooker, who in 1849 had traversed through Sikkim and Nepal into the Tibetan kingdom.

On his first visit to the Tashi Lhunpo monastery in 1879, he studied Tibetan culture and its customs very diligently, impressing the prime minister to such a degree that he was invited a second time.

Following his second 14-month stay in Tibet, Das wrote two detailed reports, which were kept confidential until 1902, when they were compiled into a book “Journey to Lhasa and Central Tibet.”

“Sarat Chandra Das was taken by the Tibetans as one among the long line of scholars who had brought new knowledge and wisdom from India, the land of the Buddha. He himself, on the other hand, had seen Tibet as a high and dry repository of priceless ancient texts and belief systems that had been ravaged in India by bigots and tropical climate.

The fascination and respect was mutual, and he returned with two yak-loads of rare books and manuscripts, splendidly pulling off a mission fraught with great hardship and danger. He was feted by the British government for this, and was sent to China as part of a diplomatic mission,” writes Parimal.

Nonetheless, travelling to Tibet in the early months of the winter was fraught with danger. “How exhausted we were with the fatigue of the day’s journey, how overcome by the rarefication of the air, the intensity of the cold, and how completely prostrated by hunger and thirst, is not easy to describe,” Das writes.

Photo Source: Representative Image

In fact, at one juncture, a village council allows Das and his entourage to pass under the condition that he answer questions on Buddhism. Despite passing the test, locals were of the impression that he wouldn’t make it past the snowy, remote mountain passes.

Nonetheless, he made it to Tashi Lhunpo, where he stayed for five months before proceeding to Lhasa. He stayed there, despite the presence of Chinese officials who were determined to rebuff any attempt by outsiders to traverse through Tibet. In fact, villagers unwilling to bend to the will of Chinese officials stationed there were often whipped with bamboo sticks.

Before the break of summer, Sarat Chandra Das began his sojourn to Lhasa. Unfortunately, on the way, he was afflicted by smallpox. On the verge of death, he was fortunately treated by a local quack. Finally, on one fine May evening, Das and his entourage arrive at Lhasa.

“It was a superb sight, the like of which I have never seen. On our left was Potala with its lofty buildings and gilt roofs; before us, surrounded by a green meadow, lay the town with its tower-like, whitewashed houses and Chinese buildings with roofs of blue glazed tiles. Long festoons of inscribed and painted rags hung from one building to another, waving in the breeze,” Das writes.

At the Potala Palace, he somehow manages to slip into a group of pilgrims who were scheduled for an audience with the 13th Dalai Lama, “a child of eight with a bright and fair complexion and rosy cheeks.”

Das describes Lhasa in immaculate detail—a city immersed in grandeur marked by the nine-story Potala Palace and the 1200-year-old Jokhang Temple, and the inner-city lanes drenched in poverty and squalor.

Every little detail about the Tibetan system of government, religious authority and hierarchy, administration and even matters of taxation are detailed in his writings. There are detailed segments about everything—the practice of polyandry, tea-drinking etiquettes, cuisine, life in the villages, flora and fauna, and the different layers of Tibet’s material and spiritual existence.

Also Read: Remembering The Extraordinary Musafir From UP Who Connected India & Central Asia

After spending a mere two weeks in Lhasa, Das returned to India through Tashi Lhunpo once again and came back to base in Darjeeling.

Das was so captivated by Tibet that he named his house on the edge of the Darjeeling town, Lhasa Villa. The rest of his life was spent in translating Tibetan texts, penning his famous Tibetan-English dictionary.

Unfortunately, the events following his departure are marred by tragic violence.

Once Chinese or Tibetan officials had found out about Das’s antics, Lama Sengchen Dorjechen, a high-ranking Buddhist scholar who had taught him Buddhist philosophy at Tashi Lhunpo, while learning science and mathematics in return, was executed and the body thrown into a river. Other accounts suggest that Tibetan officials had executed him for allowing a foreigner to enter, learn and stay in Tibet. Anyone else who assisted Das either met with the same fate or sent to prison.

Sarat Chandra Das’ reports on Tibet also laid the groundwork for the British invasion of Tibet in 1904 led by Colonel Francis Younghusband. While the Dalai Lama escaped to Mongolia, and subsequently China, many Tibetans who had stayed back to fight were crushed by the British forces.

The Tibetan kingdom was forced to sign the Treaty of Tibet with the British. As per the treaty, the British were allowed to trade in Tibet, while the kingdom was forced to pay a large indemnity of Rs 7,500,000. It was later brought down by two-thirds under the condition that Chumbi Valley come under British administrative control. Two years later in 1906, the Chinese Qing Empire re-worked the Treaty of Tibet and came up with the Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1906.

For a fee, the British agreed “not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet,” while China promised, “not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet.”

The British had succeeded in pushing the Russians back.

Sarat Chandra Das, meanwhile, was discarded by the British after his return home. Embittered, he began writing in nationalist publications, while continuing his pursuit of Tibetan Buddhist philosophy. He remains one of the great scholars of Tibetan Buddhism.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167