Swimmer Escaped the British in the Ganga, Suffered Bullet Wound & Won Gold For India

Legendary swimming champion Sachin Nag won India’s only gold medal in swimming at the Asian Games. Yet few know his incredible story.

Millions of Indians joined Mohandas Karamchand (Mahatma) Gandhi’s call for mass civil disobedience against British colonial rule in 1930. Popularly known as the Civil Disobedience Movement, it was marked by protest rallies across a plethora of villages, towns and cities. Among the millions who participated in this landmark movement was a 10-year-old boy.

Attending a public rally along the banks of the Ganga in Varanasi, a holy city in present-day Uttar Pradesh, this young boy got caught in the midst of a police crackdown.

As they began lathi-charging protestors, this 10-year-old boy “jumped into the River Ganges to hide from the police in between the boats” and hid underwater. Meanwhile, as a 2014 media report notes, “a 10 km swimming competition was going on over the Ganges.”

“To hide himself, he also joined the competition group,” the report goes on to add. To everyone’s bewilderment, he finished third in this race. It was the start of something special.

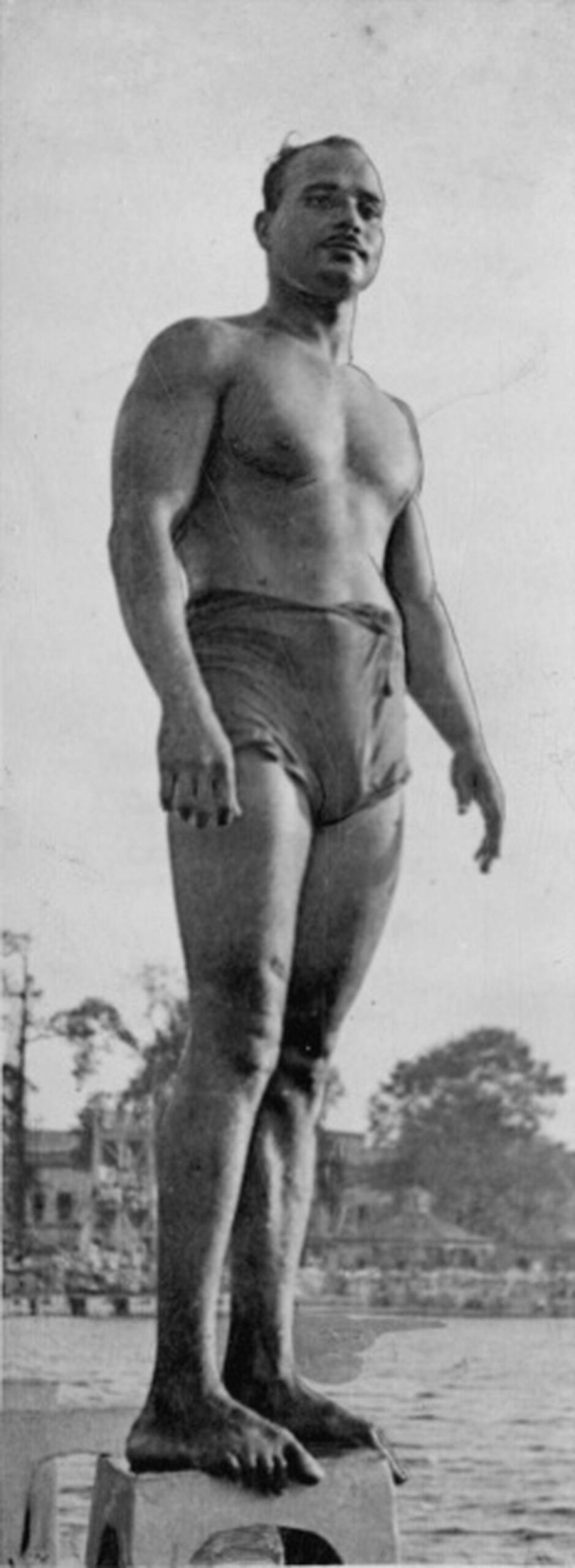

The young boy’s name was Sachin Nag, a legendary swimming champion and gold medal winner in the men’s 100 m freestyle event at the 1951 Asian Games in New Delhi. Till today, it remains India’s only gold medal in swimming events at the Asian Games.

For the love of swimming

Born into a Bengali family in Varanasi in 1920, Nag found his love for swimming on the Ganga. From the moment he surprised everyone in that accidental race in 1930, he competed in many local swimming competitions till 1936 and often finished in the first two positions.

In the following year, Jamini Das, a well-known swimmer, coach and captain of the Indian water polo team in the 1948 London Olympics, made his way to Varanasi from Kolkata (Calcutta). Representing the Calcutta-based Hatkhola Club, Das was accompanied by young swimming talent who had come to compete in a competition in Varanasi. At this competition, Das saw a young and untrained Nag beat the best his club had to offer.

Upon witnessing this talent, Das invited Nag to come to Calcutta and train with him. In this new bustling city, the young Nag trained with the club and stayed at Das’ house. For Nag, moving to Calcutta was the break he needed to train and compete at a higher level. Nag began training and competing on behalf of the Hatkhola Club in the Bengal state championships.

Suffice it to say, he beat the best the region had to offer, starting with the 100 m and 400 m freestyle events in 1938. In the following year, he equalled the national record for the 100 m freestyle event with a time of 1 minute and 4 seconds. At the same competition, he broke the record in the 200 m freestyle event with a time of 2 minutes and 29 seconds. In 1940, he broke the 100 m freestyle record set by fellow swimmer Dilip Mitra with a time of 1 minute and 4 seconds.

According to his biography, this record stood for 31 years. He would go on to win the state 100 m freestyle title continuously for nine years. By the mid-1940s, however, Nag began harbouring dreams of competing on a world stage, particularly the London Olympics of 1948.

Tragedy followed by resilience

Tragically, a year before in January 1947, Nag suffered a serious injury which could have jeopardised his chances of making it to the Olympic Games. This was a time of great violence and chaos. Only a couple of months earlier, Calcutta had witnessed bloody communal riots.

While there isn’t much evidence of how the accident actually took place, what remains uncontested is that Nag was returning from a training session when a bullet struck him on his right leg, shattering his femur. Severely injured, he was admitted to a hospital for five months.

After he was discharged, the doctor told him that it would take at least two years before he could get back to swimming. It was evident that Nag’s chance at competing in the Olympics was under severe jeopardy. Determined to compete, he resumed training just six months after the injury.

To facilitate his recovery, he returned to his family in Varanasi and rejoined a local swimming club while getting treatment from local masseurs. But recovering from a serious injury wasn’t the only hurdle he had to overcome. Back in the late 1940s, athletes representing India had to bear a great deal of the expenses required to compete in such tournaments.

To pay for his trip to London, he took up work washing vehicles in the wee hours before training. Despite taking up all sorts of work, he couldn’t gather the requisite funds. Nag was about to give up on his dream when Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, a singer, heard about his plight and decided to raise funds. One of the ways in which the singer raised funds was through a musical performance at the Uttara Cinema Hall in North Calcutta.

Nag finally had the money to realise his dream of competing in the Olympics. He finished in sixth place at the 1948 London Olympics in the 100 m freestyle event. What’s more, he also played for the Indian water polo team and scored four goals in a 7–4 win versus Chile.

Moment of Glory

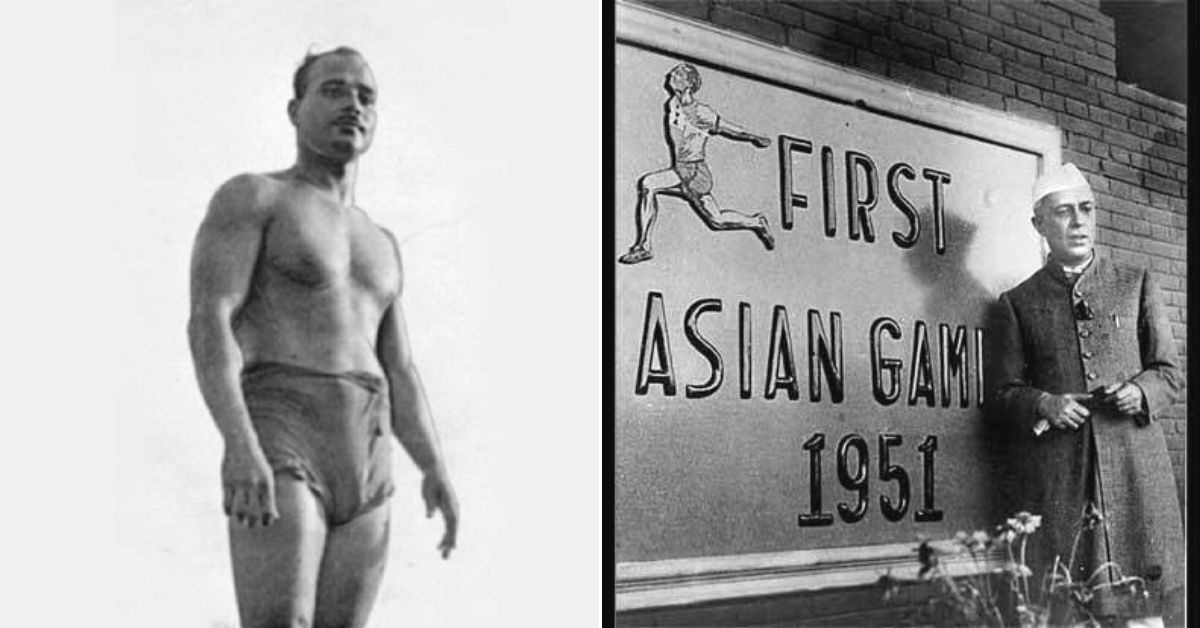

Nag’s moment of glory, however, came three years later at the inaugural edition of the Asian Games in New Delhi. In a dazzling display on 8 March, 1951, he secured gold in the 100 m freestyle event with a time of 1 minute and 4.7 seconds.

Watching Nag perform his magic in the audience was Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. According to media reports, Nehru was so overjoyed that he broke protocol, embraced Nag, and presented him with the red rose from the breast pocket of his coat.

According to press reports, Nag noted how this was one of the greatest moments in his life. Besides winning gold in the 100 m freestyle, he also picked bronze medals in the 4×100 m freestyle relay and the 3×100 m freestyle relay. He would also go on to compete in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, representing India in water polo.

Following his incredible achievements in the pool, he would train future generations of Indian swimmers — including Arati Saha, the first Asian woman to cross the English channel in 1959, and Nafisa Ali, a national champion in the early 1970s who was also crowned Miss World.

Desire for recognition, acknowledgement

Despite his many achievements for the country against incredible odds, Nag passed away on 19 August, 1987, without real recognition or financial support.

Speaking to The Hindu in 2014, Ashoke Kumar Nag, his son and a Kolkata-based insurance agent at the time, recalled, “He yearned for recognition from the government. Not financial considerations but the acknowledgement of his service to the sport and the country.”

For years, Ashoke tried to secure his father’s legacy but was often met with bureaucratic apathy and rejection. On multiple occasions, he reached out to the Sports Ministry to bestow an award to his father posthumously in recognition of his achievements, and he never gave up. If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change. Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution- By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike. Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

In August 2020, Nag was awarded the Dhyan Chand Award for lifetime achievement in sports. Finally, one of post-Independence India’s first sporting superstars received the recognition he deserved. Ideally, he should have been celebrated during his lifetime, but better late than never.

(Edited by Pranita Bhat; Pictures courtesy Wikipedia and Twitter)

Sources:

‘Honour for pool pioneer’ by Arindam Bandyopadhyay; Published on 29 August 2020 by The Telegraph

‘Sachin Nag – a forgotten legend by Vijay Lokapally’; Published on 29 September 2014 by The Hindu

‘The long wait ends for India’s first Asiad gold medallist Sachin Nag’ by Nihal Koshie; Published on 29 August 2020 for The Indian Express

‘India’s first Asian Games gold medallist Sachin Nag’ by Venkat Ananth; Published on 29 September 2014 by Livemint

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167