How Do You Prevent a Communal Riot? We Asked the Cop Who Didn’t Let Bhiwandi Burn

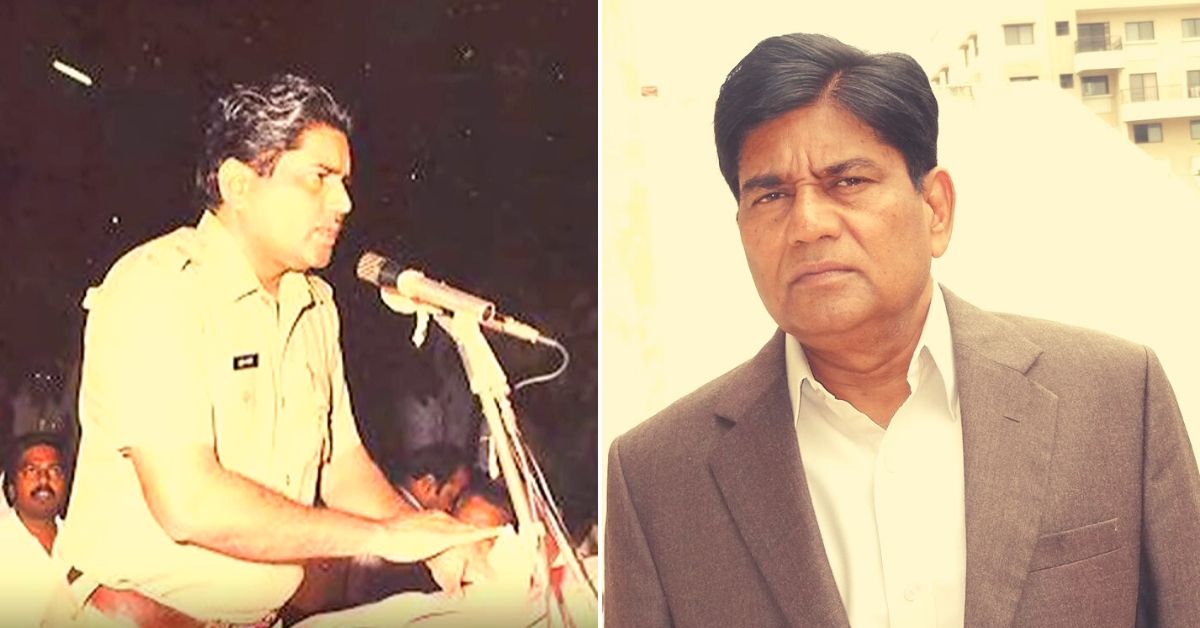

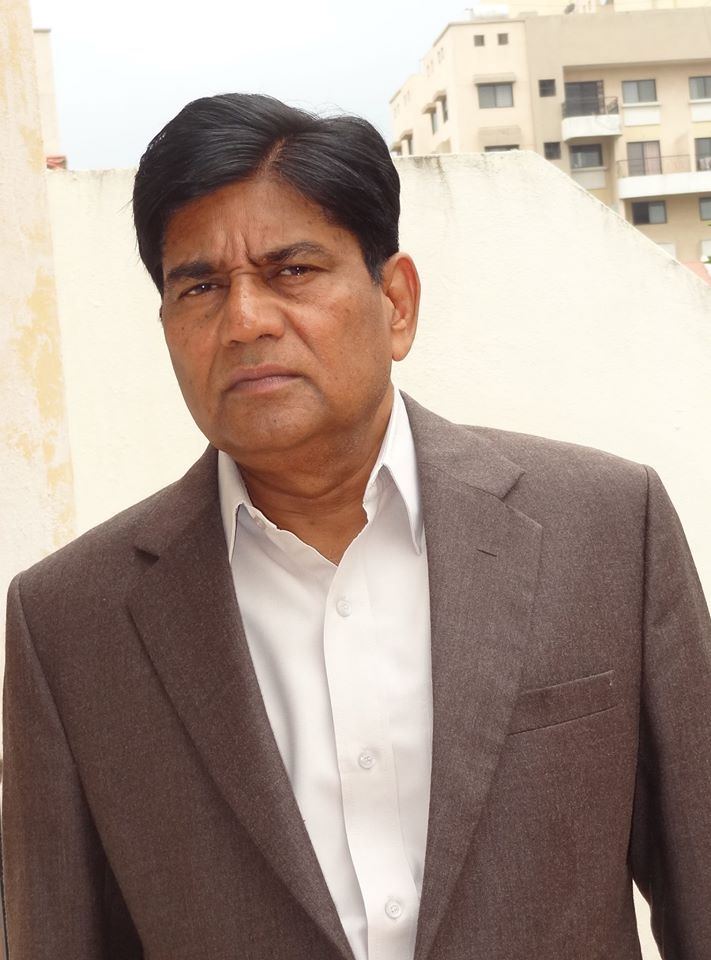

A winner of the President's Gallantry Award, now-retired IPS officer Suresh Khopade prevented the communal hotbed of Bhiwandi from descending into violence even as neighbouring Mumbai burnt during the 1992-93 riots.

Before Suresh Khopade was posted in Bhiwandi, an industrial city located 20 km northeast of Mumbai, as its Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) in 1988, it was known as a hotbed for communal violence.

Rocked by major communal riots in 1965, 1968, 1970 and 1984, alongside multiple minor skirmishes, the city had lost hundreds of its residents to violence. During the riots in 1984, the army had to be called in to quell the frenzy.

Making matters worse, institutions like the police and judiciary had failed to punish any of the suspected killers or arsonists. In the 1984 riots, police had arrested 962 persons. A special court was set up to adjudicate on these cases, working for 16 months.

According to Khopade, out of 962, a stunning 961 were acquitted. Only one person was convicted for five years of rigorous imprisonment and a Rs 2,000 fine, but he was acquitted on appeal. Something had to change, particularly with growing communal polarisation through the 1980s. The status quo was unacceptable. That’s when he devised and pioneered a unique community policing system built on mohalla (neighbourhood) committees in 1988.

This system prepared the city and its residents so well that when riots broke out in Mumbai in 1992-93, killing thousands, Bhiwandi saw peace and zero casualties.

A winner of the President’s Medal for Gallantry in 1993, Khopade today is a retired Indian Police Service Officer. Earlier this week, he spoke to The Better India about how the systems he put in place saved Bhiwandi from communal violence and mayhem.

Studying the problem

Born and raised in Pune, Khopade was a graduate in agricultural sciences who cleared the Maharashtra Public Service Commission exam and enlisted with the state police in 1978.

In his first posting as Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) in Panvel, Raigad district, he was involved in a brutal encounter with two dreaded dacoits. He suffered bullet injuries on his chest, thigh and leg, but managed to eliminate both dacoits.

Following this stint, he was promoted to the rank of Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) and posted in the Intelligence Wing of the state Criminal Investigation Department (CID) where he was in charge of overseeing cases of communal violence.

There, he studied a majority of the communal riots that had taken place in Maharashtra and Gujarat and found some serious problems with the way police dealt with riots.

“I discovered that the police had a fire-fighting approach towards handling communal riots. They wait for a call, approach the site of violence, attempt to disperse the mob and impose law and order using whatever means they have at their disposal like lathi charging, tear gassing, firing and arresting people. They then investigate the cases, draw up chargesheets, present them in court and come back to the station. Instead of preventing communal violence, the focus was on merely stopping its escalation,” he says.

In 1988, he was transferred out to Bhiwandi, a posting not desired by many officers because of its reputation for communal violence. But instead of fear, he saw this as an opportunity to fix a long-standing problem. His next step was to collect all the case diaries associated with the riots in 1984 and begin studying all of them.

“After reading them, I began meeting the families of the victims from both Hindu and Muslim communities. Each one had a harrowing story to tell of seeing their loved ones being brutally killed by mobs. I sought to understand why they were targeted and killed. After the riots, politicians blamed ‘foreign elements’ for it. Senior officers in Mumbai said criminals from their city went to Bhiwandi and wreaked havoc. But I took a look at case diaries and asked the victims about who had killed their loved ones. They said that those responsible were living in their neighbourhood or nearby. The perpetrators were locals,” he recalls.

DCP Khopade went onto study the backgrounds of 243 accused persons and found that only 3.8% had a criminal background. The remaining were ordinary residents.

He also went onto study their economic background and found that nearly 95% of the people killed during the riots were living below the poverty line, while 63% of those accused of those taking part in the killing also came from the same economic class.

Many of the perpetrators of violence were conditioned in their childhood to look at the other community with hatred and suspicion.

“This compelled me to think how people from different communities staying in the same locality can be brought together on the same platform to discuss their issues peacefully and ensure harmony,” he recalls.

Mohalla Committees Solution

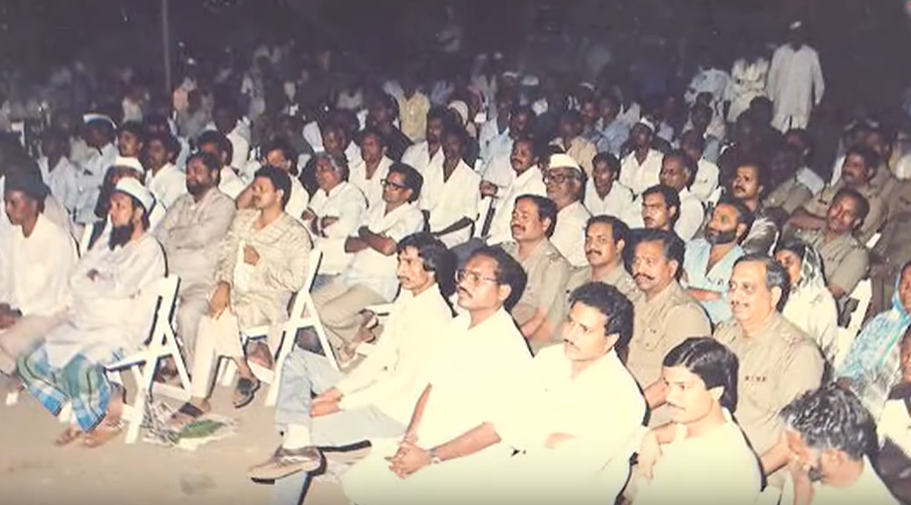

By 1988, the local police established 70 Mohalla Committees, where a group of people belonging to diverse religious and social groups, but living in the same locality come together to discuss developmental concerns in their neighbourhoods and promote social harmony.

Each mohalla had about 50 members (although this number varied over time) each from the Hindu and Muslim communities respectively. Also, due consideration was given to include members from different walks of life like a taxi driver, rickshaw puller, loom worker, farmer, doctor, lawyer, journalist and teachers who reside in the same mohalla.

Only the communally diehard, the accused in the ‘84 riots and other ‘anti-social elements’ were kept away. These committees were presided over by the head constable and constable, the lowest-ranked personnel in the police force. They were asked to convene a meeting once in a fortnight not in the police station, but in the very mohalla itself.

Public places like a government school building, community halls or open ground were chosen as venues. The head constable or sub-inspector always presided over the committee and not any resident of the mohalla.

In these meetings, citizens freely discussed any problem, whether a civic concern, complaints about criminal or communal elements.

“We started bringing all non-cognizable cases to these committees for resolution. The meeting was presided over by the head constable or sub-inspector, and all petty matters were resolved. Nearly 95% of the complaints police stations receive were non-cognisable in nature like improper disposal of garbage by one family, a dispute over the share of water supply, family and property disputes, fights between their children, etc. Every big crime begins with a small dispute/offence. Once we prevent these small disputes from escalating, you automatically put a stop to the commission of a bigger crime. Moreover, people in these forums know who committed these petty acts of crime, where they live and what they do. Here the head constable invokes the law, guides the people and implements the decision, which is far better than any long-winded judgement given by a court,” argues Khopade.

Taking one step further, the police would assist citizens in resolving their concerns even with the local municipality, ration shop or even the electricity department. More importantly, however, these meetings brought people together from different communities.

“When Ram Lal and Abdullah (representative names) started sitting together in these meetings, the respective prejudices they had of the other’s community began to diminish. They started becoming friends over time. Ram Lal understood that Abdullah didn’t have five wives and eight children as communal propaganda would state, but was just like him with one wife and three children. Like Ram Lal, Abdullah thought about bettering his own home, mohalla or Bhiwandi and never thought about Pakistan. Similarly, Abdullah realised that Ram Lal doesn’t want to eradicate Islam from India and has the same day to day concerns like water supply, electricity and everyday bills,” he recalls.

More importantly, the Head Constable had made hundreds of friends in the mohalla cutting across caste, occupation and religion. This strengthens the intelligence machinery in the local police. The committee members would regularly inform the police representative present at the Mohalla meetings about the local troublemakers and any trouble brewing in their locality.

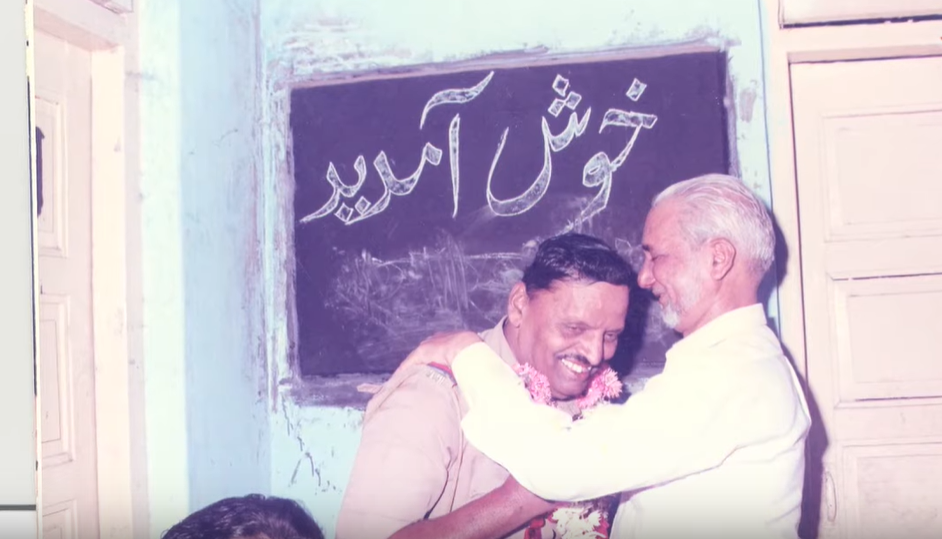

Their relationship grew to such an extent that if there was a marriage function, religious ceremony or any social event, the mohalla committee would invite the said constable. Over time, the local beat constable’s respect in the community grew.

Since all members of the mohalla would meet with the constable regularly, the scope for petty corruption also came down significantly with greater transparency.

“As DCP, I ordered my officers like the local inspector to visit these mohallas, talk to the residents, develop a relationship with them and get a feel of the place. This resulted in a great attitudinal change in the local police force. As DCP, I couldn’t give my juniors, particularly the constables, an increase in salary or rank, but what I did give them was some semblance of authority, self-esteem and dignity in running these mohalla committees. This inspired them to work with greater vigour,” says Khopade.

In other words, the relationship that was established between the neighbourhood police and community turned from one of fear and force to one of harmony, belief and humanity.

Preparation for the 1992-93 Bombay Riots

When DCP Khopade was transferred out in March 1992, his successor Gulabrao Pol continued this initiative. “I would attend these community meetings at least twice a week. Whatever their complaints or concerns, we would investigate them,” said Pol, speaking to Satyamev Jayate, an Indian television talk show.

Little surprise that when communal riots in Mumbai and different parts of the country broke out in December 1992 and January 1993 following the demolition of the Babri Masjid, Bhiwandi remained an ocean of peace without any violent outbreaks.

So, when the riots broke out in Mumbai, all the mohalla committees got together, the resident constables began patrolling the area and were receiving real-time information from residents about troublemakers collecting arms, stones or those trying to organise mobs, which made investigating these potential trouble points easier, while also preventing any rumour-mongering.

“The attitudes of the mohalla committees were let whatever happen outside, but we will keep the peace in our neighbourhood. During the riots, only one or two neighbourhoods saw some unrest, but no one died or suffered serious injuries. Mumbai, meanwhile, burned with thousands dying and properties worth crores getting damaged or stolen,” says Khopade.

Meanwhile, in the run upto to the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, the local police had compiled a list of 232 known troublemakers and 25 gangsters who they would detain. The local police also began training exercises in riot control, mainly to tackle stone and bottle-throwing mobs. According to this 1993 report by Indian Today:

“It held route marches with NCC cadets and a police band and even organised social events such as a road run—calling it Ekta Daur or a Run for Unity—and a poetry festival. By December 6, people were primed for peace. And after, there were mobile police forces with officers leading from the front…It paid off. In one Muslim locality, for instance, some youths stoned a police picket injuring an assistant sub-inspector in the head. But the police did not overreact, and the locals helped in the arrest of three culprits.”

If the ordinary beat constable and citizens are working together in close coordination, there is no question that the state can maintain peace and harmony. What Suresh Khopade built in Bhiwandi is a beautiful illustration of how community policing can work for the people.

“This experiment of the Mohalla Committee has been replicated in many parts of India under different names and has achieved success in addressing the problems of communal conflict by promoting civic engagement between the two communities. The Mumbai Police too have embarked on a major initiative of engaging the citizens as co-producers of their safety and given shape to what has come to be known as Mohalla Ekta (Neighbourhood Unity) committees that have played an important role in maintaining peace in difficult situations,” notes the book titled ‘Policing Muslim Communities: Comparative International Context.’

“The Bhiwandi Experiment was not just about keeping the peace between Hindus and Muslims, but a complete revamp of police organisation—making constables take part in the decision making process, change their attitudes to people, change their minds, etc. We must empower our constables because they work amidst the people. Anything that happens, the constable is the first person on the scene. But no importance is given to them. They don’t receive proper training and aren’t taught a proper approach. We must train them into a professional force bereft of prejudice. The lack of proper in-service training given to them hurts their ability to do a proper job,” says Khopade.

In the years following his transfer from Bhiwandi, his successors kept the system going for a while, but today he admits that mohalla committees don’t meet as often as they should.

“Once, the Mohalla Committees became famous as the ‘Bhiwandi Experiment’ after no Hindu-Muslim riots occurred during the demolition of Babri Mosque. However, the local meetings became irregular, and the local efforts were too weak to prevent riots between members, police officers, and residents after the late 1990s,” says a 2015 study published in International Journal of Social Science and Humanity.

Nonetheless, it’s imperative to take the positives and implement elements of this system so that events like the recent Delhi Riots don’t happen ever again.

(Following the success of this policing model, Suresh Khopade later went on to write a book in Marathi titled ‘Mumbai Jalali Bhivandi Ka Nahi’, which documents his efforts. It has been translated into English titled, ‘Why Mumbai Burned…And Bhiwandi Did Not’.)

Also Read: 8-Hour Work Shifts & Overtime Pay? Do Our Police Deserve This?

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.