Refusing a Life of Isolation, How an 18-YO Widow Became India’s 1st Female Engineer

Married at 15 and widowed at 18, Ayyalasomayajula Lalitha chose to pursue a career in engineering instead of conforming to the reclusive life widows were forced to live. She went on to become India’s first female engineer and a vocal advocate for women's rights.

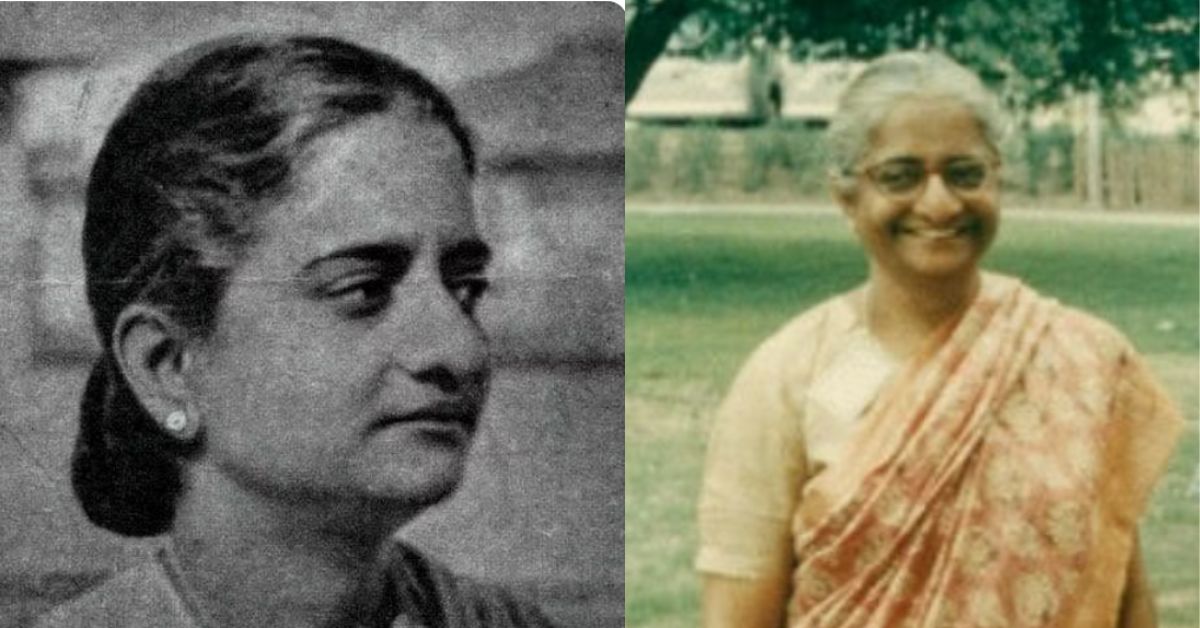

Picture credit for featured image: Women of College of Engineering, Guindy/ Facebook (L)

In 1937, Ayyalasomayajula Lalitha faced the daunting task of raising her four-month-old daughter after losing her husband. As an 18-year-old widow, she was expected to conform to a life of isolation and perpetual sorrow, but the forward-thinker chose to defy societal norms.

Instead of succumbing to the societal pressures of widowhood — shaved head, a strictly restricted life, and banishment from society — she decided to pursue a career in engineering, a male-dominated field at the time.

This decision would, later on, make Lalitha India’s first female engineer.

The path she traversed

Born in 1919 in a middle-class Telugu family in Chennai, A Lalitha was the fifth of seven siblings. Her brothers had become engineers, while her sisters were limited to basic education. Despite being married off at the age of 15, her father believed in her education and ensured she completed her studies up to Class 10.

Her daughter, Syamala Chenulu, who now lives in the United States, said, “When my father passed away, mom had to suffer more than she should have. Her mother-in-law had lost her 16th child and took out that frustration on the young widow. It was a coping mechanism and today, I understand what she was going through. However, my mother decided not to succumb to societal pressures. She would educate herself and earn a respectable job.”

Lalitha did not want to be a doctor, as medicine requires professionals to be available around the clock. So she chose to become an engineer like her father Pappu Subba Rao and her brothers.

Rao, a professor of Electrical Engineering at the College of Engineering, Guindy (CEG), University of Madras, spoke to K C Chacko, the principal of the college and to the director of Public Instruction, R M Statham. Both officials were supportive of admitting a woman, a first in CEG’s history.

“Contrary to what people might think, the students at amma’s college were extremely supportive. She was the only girl in a college with hundreds of boys, but no one ever made her feel uncomfortable; we need to give credit to this. I used to live with my uncle while amma was completing college; she would visit me every weekend,” Syamala said.

But a few months into the college, Lalitha started feeling lonely in the hostel and conveyed this to her father. Rao took this as a sign to invite more women to the college and opened up the admissions. That’s how Leelamma George and P K Thresia soon joined in, but for the civil engineering course.

She worked for a brief period with the Central Standard Organisation in Shimla. Later, she also worked with her father in Chennai, assisting him in inventing Jelectromonium, an electrical musical instrument, an electric flame producer, and smokeless ovens. But within nine months of joining her father’s workshop, Lalitha took up a job in the Associated Electrical Industries in Kolkata.

The pioneering spirit that did not end with her degree

Lalitha continued to make significant contributions to her field throughout her life. In her 20-year career, she worked for several organisations, including the Central Standard Organisation, Associated Electrical Industries, and the Indian Standards Institution. She also served as a consultant to the United Nations on engineering projects in Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

Apart from her professional career, she was also involved in several women’s organisations — including the All India Women’s Conference and the National Federation of Indian Women. She was a vocal advocate for women’s rights and gender equality, and believed that women should have equal access to education and employment opportunities. She worked tirelessly to promote these ideals.

Lalitha was eventually recognised for her contributions to the field of engineering and women’s rights. She was also invited to attend the First International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, where she represented India. Here’s where she had very famously said, “150 years ago, I would have been burned at the funeral pyre with my husband’s body.”

Syamala says that it was during this conference that she realised the importance of her mother’s influence on people, especially women, around the world. If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change. Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution- By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike. Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

“But what I take from her life is her extreme patience towards people and the quality of doing instead of just talking. She never remarried and never made me feel the absence of a father in my life. She believed that people come into your life for a reason and leave when the purpose is over. I never asked her why she never got married again. But when my husband asked her, she replied, ‘To take care of an old man again? No, thank you!’”

Edited by Divya Sethu

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167