How This Ex-British Soldier Became The Pioneer Behind Kabini & India’s Eco-Tourism

Colonel John Wakefield, fondly known as 'Papa Wakefield' was one of India's quiet, dedicated and effective wildlife defenders who turned wildlife tourism into a significant conservation tool.

Attending the Pacific Asia Travel Association (PATA) conference in Kathmandu, Nepal, back in 1978, Karnataka’s tourism minister at the time, R Gundu Rao, was given lodging at the famous Tiger Tops Jungle Lodge at the Royal Chitwan National Park.

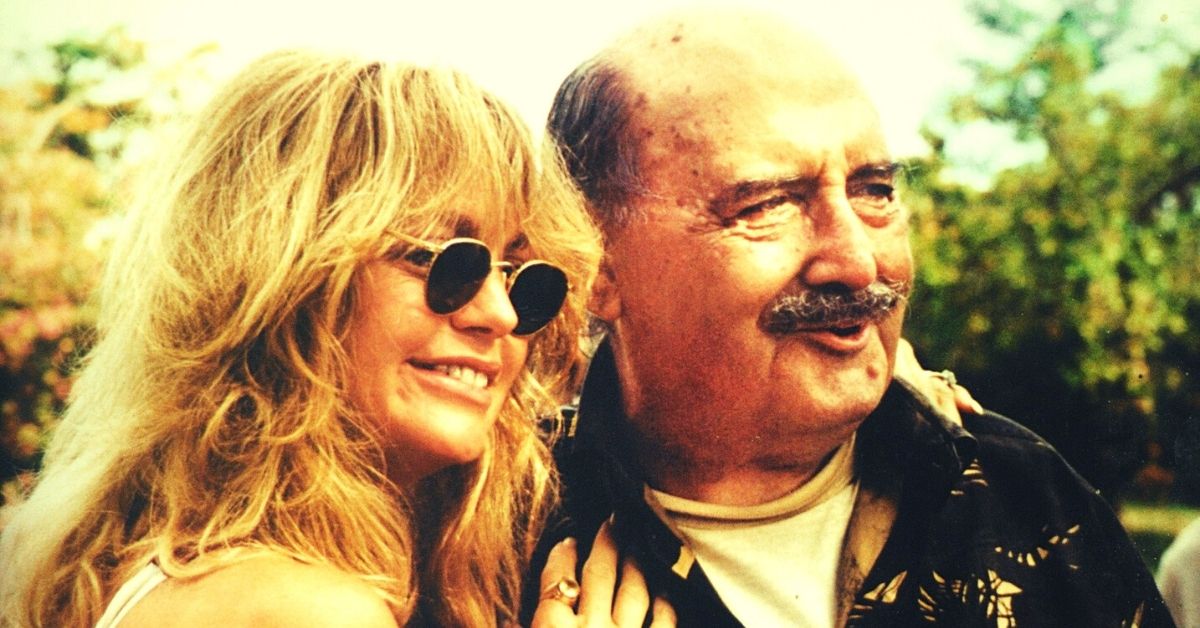

(Image above of ‘Papa’ John Wakefield with American actress Goldie Hawn at Kabini River Lodge courtesy JLR)

Deeply impressed by the resort—its facilities and the model of leveraging Chitawan’s stunning natural beauty to attract tourists in a responsible manner—Gundu Rao felt a similar model could be adopted in his home state which was home to a myriad of wildlife species.

Upon his return, he invited Tiger Tops to open a similar resort at the Rajiv Gandhi National Park or Nagarhole in Karnataka. Jim Edwards, the owner of Tiger Tops, sent two men to fulfill this demand—Ramesh Mehra and Colonel John Felix Wakefield. A year later, the Government of Karnataka announced that it had entered into a partnership with Tiger Tops and unveiled Jungle Lodges and Resorts, India’s first venture into eco-tourism.

However, the idea of constructing a lodge inside Nagarhole was junked when it was declared a national park since as per the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, any construction of commercial tourist lodges was prohibited in a declared forest area. Instead, Mehra and Wakefield searched for locations where they could set up this resort and found a former hunting lodge of the Maharaja of Mysore in Karapur on the northern banks of the Kabini river.

Developed as a joint venture between the Government of Karnataka and Tiger Tops, the Kabini River Lodge was open to the general public in 1980. But a couple of years after the lodge was opened to the general public, Tiger Tops withdrew from the partnership and sold off their stake to the Government of India. Today, it’s 100 per cent owned by the Karnataka government. In the decades since the River Kabini Lodge was opened, it has earned a reputation of being one of the best wildlife resorts in the world and established a model for eco-tourism, which is today a major instrument of wildlife conservation efforts all over India.

What’s interesting to note is that while it was Gundu Rao who came up with the idea, it was the work of a former British soldier, conservationist and former employee of Tiger Tops, Colonel John Felix Wakefield, fondly known as ‘Papa’, who ensured that India’s first eco-tourism venture took off. He remained the lodge’s resident director for the following few decades.

Unlike conventional tourism, the objective of eco-tourism is to educate the tourists about their natural surroundings and help them develop a genuine appreciation for it. These initiatives are also about ensuring that local communities living in and around these forests are made genuine stakeholders. Suffice it to say, our natural forests are best protected by educating visitors along with sustaining the livelihood of local communities.

As the resident director, ‘Papa’ Wakefield was instrumental in applying these principles.

An Englishman Who Made India His Home

Born on 21 March 1916 in Gaya, Bihar, Wakefield came from a long line of Englishmen, starting with his great grandfather who came to India in 1826 to join the army of the erstwhile Bengal Presidency under the East India Company. His father, meanwhile, was employed by the Maharaja of Tikari in Bihar.

Growing up, it was in the private forest of the Maharaja, where he picked up his first passion for hunting. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that he shot his first tiger at the age of 9 and first leopard when he was 10. It was a childhood largely filled with fun and adventure, but his father soon sent him to England for his formal studies. Upon his return to India, he furthered his passion for hunting, and even met the legendary Jim Corbett on such hunts.

“During the war (World War II) in 1941, he had enlisted in the Emergency Commission of the British Army which took him across North India and Burma. Fighting in Burma, Wakefield also succumbed to the typical war-time romance. He met and married a British nurse working in Q A Army Hospital. But after his wife’s father fell seriously ill, the family left for England in 1958. He never met her again, though his two daughters and their children visited him often in India,” notes this profile on Wakefield published in the Deccan Herald. It also cites another instance when Wakefield had a chance to leave India in 1948, when his mother warned him, “India is going to the dogs”. But while she left, he stayed.

After he left the army in 1954, he rekindled his passion for hunting, organising trips for tourists. But it was the growing public discourse on wildlife conservation highlighted by news of the dwindling number of tigers in the early 1970s and the subsequent enactment of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 that finally converted him into a conservationist.

Kabini Lodge: Introducing Eco-Tourism to India

When Tiger Tops split from the Jungle Lodges venture barely a few years after their partnership with the Government of Karnataka was announced with much fanfare, it was Wakefield who held fort at the Kabini River Lodge.

The challenges of running such a venture were immense. For starters, various environmentalists of the day panned the very rationale of wildlife tourism and establishing jungle lodges in Karnataka’s wildlife sanctuaries.

Some called it “ecocide” while others raised concerns about how such establishments would “upset the delicate balance between nature and wildlife”.

Nonetheless, one official at the Jungle Lodges and Resorts venture responded to this criticism by saying, “We are trying to introduce wildlife tourism in a highly specialised, scientific way. Our accent is on quiet, thoughtful and unobtrusive tourism. It would be a harmless way to watch wildlife. And the revenue earned could be used to promote wildlife.”

Meanwhile, there were obstacles set from within with the government bureaucracy trying to impose their own ideas on how this venture would work, besides the forest department’s instinctive suspicion of ‘intruders’ like Colonel Wakefield. But he won them over with his vast knowledge of the jungles, his affable manner and of course his ability to recognise the importance of the local population in ensuring such ventures succeed.

As Geeta Doctor, a Chennai-based journalist and writer, notes in her profile of Wakefield for the Business Standard:

He [Papa Wakefield] was one of those who believed that while it’s the animals who are the prime species in a jungle resort, people also matter.

The local population makes up 90 per cent of the staff at Kabini. At the same time, the hunter-gatherer tribes of the surrounding jungle, the Soligas, have continued their original pursuits as collectors of honey, their villages left undisturbed in the interiors of the forest.

He was aware of how, when the dam was built across the Kabini River at Beechanahalli, many of the older settlements had to be relocated, and how it was that the ancient temples and sacred groves that had been washed away could never be replaced.

That they would be supplanted by a country liquor shop, a permanently shut village dispensary and an ugly cement-and-grilled-metal, asbestos-sheeted shed to house the earlier gods. But his approach was never confrontational. The dam had also allowed the area to become one of the best natural reserves with 250 different bird species, all manner of small and large animals to live together in close harmony with the human population.

His sensitivity to the plight of the local community living in and around the jungle is what eventually translated into the philosophy of the Jungle Lodges and Resorts venture.

As the Jungle Lodges website notes: “We source a large portion of our provisions from local farmers; our staff includes reformed poachers – capitalising on their sound knowledge of the forest and wildlife for the greater good; and our guests often leave as avid endorsers of conservation.”

Offering employment opportunities for local villagers was critical in building local support for conservation efforts. Besides involving those from the local community, the venture was also about educating tourists of the natural wonders before them.

“Wakefield hired Sundar as head naturalist [in 1986] for taking tourists from Kabini Lodge into the Nagarhole National Park, and for teaching locals to be naturalists in the park. Thus, a coherent philosophy of and practice of providing knowledgeable naturalists to accompany tourists in the forest, presenting the park’s features, was implemented by both these national parks [including Bandipur]. Assuming a strong and informative role at the tourist lodges, the naturalists for both parks offered the tourists bird walks, explanations of elephant behaviour and descriptions of the trees in the forest,” notes this chapter in a collection of essays titled ‘Animals in Person: Cultural Perspectives on Human-Animal Intimacies’.

And, of course, there was an intimate bond he shared with the animals roaming these parts, particularly elephants. In fact, some believed that he could actually communicate with them.

Until his eventual passing at the age of 94 on 26 April 2010, Colonel Wakefield soldiered on with his remarkable work in Kabini, which he had made his home for nearly three decades. Along with being credited for the emergence of ecotourism, as an instrument of conservation, in the area, the legacy he leaves behind in Kabini is unquestionable.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167