This Assamese Man Has Spent the Last 23 Years Saving the World’s Tiniest Pig

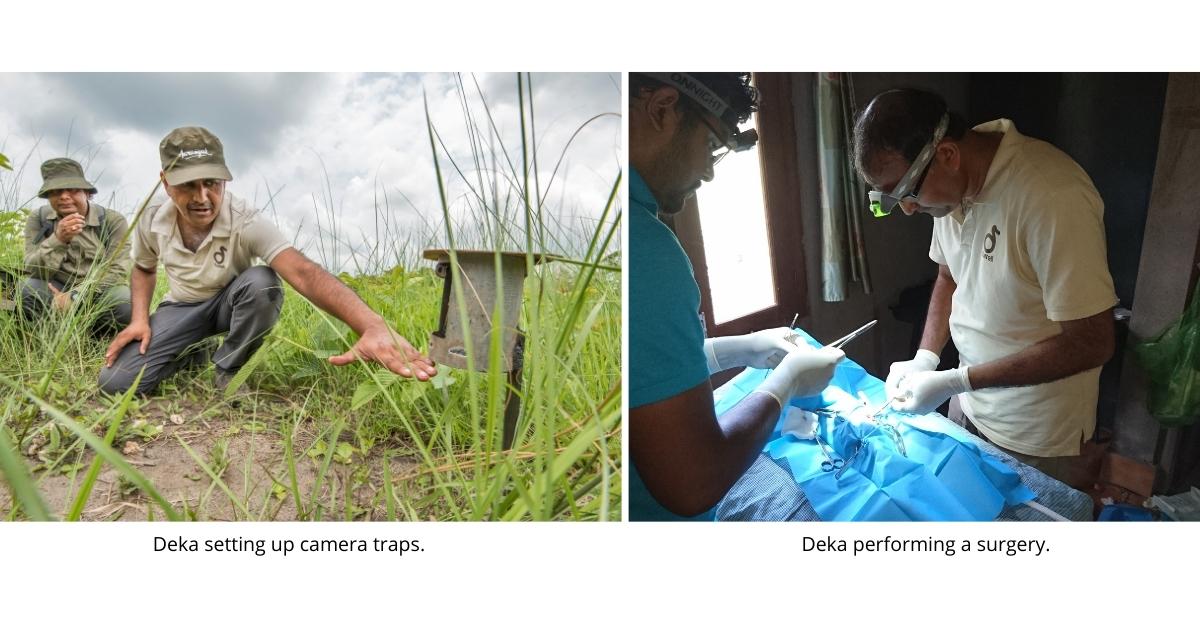

Wildlife conservationist Parag Deka has spent the past 23 years bringing back the pygmy hog from near-extinction.

Parag Deka has always had a connection with wildlife. Perhaps because he grew up in Kokrajhar, a town surrounded by Sal forests, along the Western border of Assam.

He was only eight years old when he rescued a few baby birds that lay wounded on the ground after a storm hit the state. He took them home and tended to them. Most of the fledgelings died, which he buried with a solemn prayer, but a few lucky ones recovered, and he set them free.

That was the first time he experienced the joys of saving animals. Little did he know that years later, he would be leading the brigade to save an entire species from extinction.

Deka is now a veterinarian and conservationist heading the Pygmy Hog Conservation Program (PHCP) run jointly by Indian authorities, the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, and a local NGO called Aaranyak.

“It has given my life purpose,” Dr Deka, who has dedicated his entire career to the conservation of the pygmy hogs, tells The Better India. “The way I see it, I am spending my one human life to save a whole species from extinction.”

The World’s Tiniest Pig

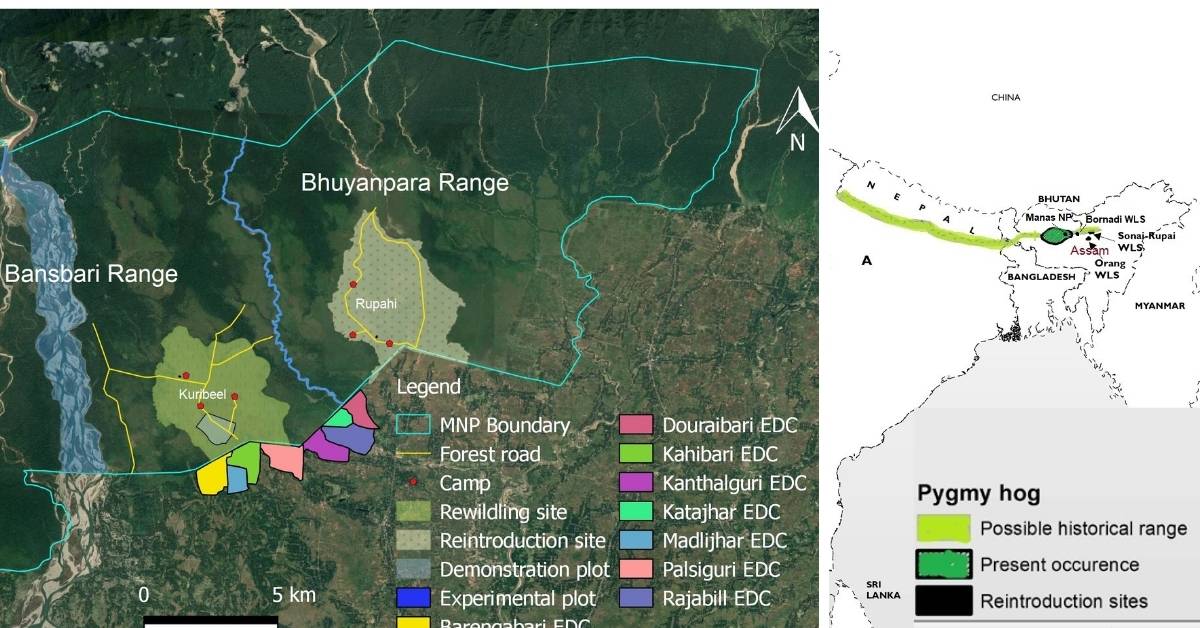

The pygmy hog is the smallest species of wild pigs known to us. About the size of a house cat, pygmy hogs are on average 60 centimetres long and 25 centimetres tall. They are extremely rare, confined to the grasslands of Assam at the foothills of the Himalayas. Surveys using droppings and other markings as well as camera traps estimate that there are now 300 pygmy hogs currently left in the wild.

They are very shy animals and hypersensitive to their environment. They can only survive in the grasslands, hiding in the tall grass, wary of predators.

Initially, these grasslands were converted into fields, farms, grazing grounds, and villages. The destruction of their habitat due to human activity is why they’re endangered today.

Because pygmy hogs are so sensitive, they act as a measure of the health of the ecosystem. Striving to conserve such indicator species indirectly contributes to maintaining their habitats, which have huge ecological and economic advantages.

Deka explains, “These wet grasslands serve as buffers against floods in the rainy season while maintaining high groundwater levels in the dry season, which indirectly benefits farming communities.”

The Pygmy Hog Conservation Program (PHCP)

It was the naturalist and conservationist Gerald Durrell’s keen interest in pygmy hogs during the ’60s and ’70s that laid the foundation for their protection.

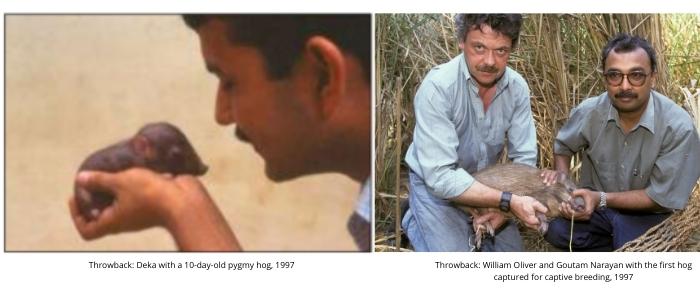

Later in 1995, the PHCP was established by biologists Dr Goutam Narayan and William Oliver of the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust (DWCT). At the time, the hog population was at an all-time low.

In 1997, Deka, who was studying a masters in veterinary science, joined the team as an intern. After the internship concluded, he had the opportunity to join a college as a lecturer, but instead, he followed his heart and stayed on with PHCP.

“I am only continuing the legacy work started by Durrell, Oliver, and Goutam,” says Deka.

How To Save A Species

Bringing a species back to life needs a multifold approach. One of the main endeavours of PHCP is conservation breeding, that is, the captive breeding of pygmy hogs with the objective of reintroducing a subset back into the wild.

In 1996, two males and four females of the last remaining wild hog population were captured at Manas and brought to Basistha Research & Breeding centre for this purpose. The PHCP always has at least 70 captive hogs at their facilities. Over the past 11 years, they have reintroduced 130 pygmy hogs in four national parks and wildlife sanctuaries in Assam (Orang, Sonai Rupali, Manas, and Barnadi).

Before reintroduction, the hogs are trained in surviving in the wild at a pre-release facility in Potasali, Nameri Tiger Reserve. The hogs survival, health, and activities are tracked using field signs such as nests, forage marks, droppings, as well as modern technology like camera traps and radio telemetry.

Another important element of the conservation action plan is the up-gradation and protection of the sub-Himalayan grasslands. Deka and his team work closely with the fringe communities in the area to spread awareness of the importance of habitat maintenance.

Bringing The Wild Hog Back To Nature

Deka recalls seeing images of the released pygmy hogs for the first time.

“Three years ago, I was in my room at Nameri scanning through thousands of camera trap pictures. It is a tedious process but we need hard evidence of how the hogs are faring in the wild after reintroduction,” says Deka.

And then he spotted the tiny hogs in two images. But they weren’t alone. The mother hogs were accompanied by their young ones. The implications were huge. They were not only surviving, but the hogs had started breeding in their natural habitats!

The reintroductions have been very successful. In Orang, the numbers have more than doubled and the hogs have migrated to areas far from the release locations. In Manas, the total count of reintroduced hogs and their offspring is estimated to have reached 200.

Starting in 2021, another 60 hogs will be released over a five-year period in the Bhuyanpara range of Manas. Efforts are underway to identify and restore other protected grasslands for reintroduction.

In the coming years, Deka’s team is looking to do for other endangered species what they have done for the pygmy hog. Guided by Durrell’s ‘Rewild Our World’ strategy, the PHCP is now working on the recovery of highly threatened animals such as the Bengal Florican, the Hispid Hare, Eastern Barasingha, and the Water Buffalo.

In order to do so, they are using a three-pronged approach: Restore (the environment), Reconnect (with the communities) and Revive (repopulate the grasslands with several endangered species).

“We have drafted a plan for until 2025, the 100th birth anniversary of Gerald Durrell, the founder of Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and whose vision has helped save the pygmy hogs from extinction,” Deka explains.

You can also help save this unique species by spreading awareness, helping raise funds and by volunteering at the conservation facilities.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167