Vizag Architect is Exploring Ladakh’s Past to Build Stunning, Eco-Friendly Homes

“My buildings should outlive me and future generations. That's why I choose natural materials on the outside and inside."

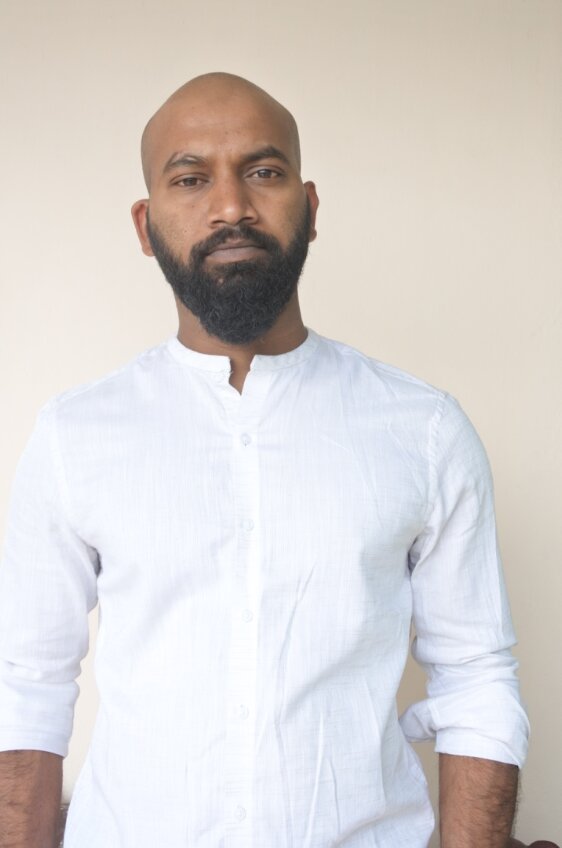

How does a man from Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh find a home in Ladakh? Meet 36-year-old architect Sandeep Bogadhi, the founder of ‘Earthling Ladakh’, who is on a mission to promote buildings made entirely of natural and locally-sourced materials.

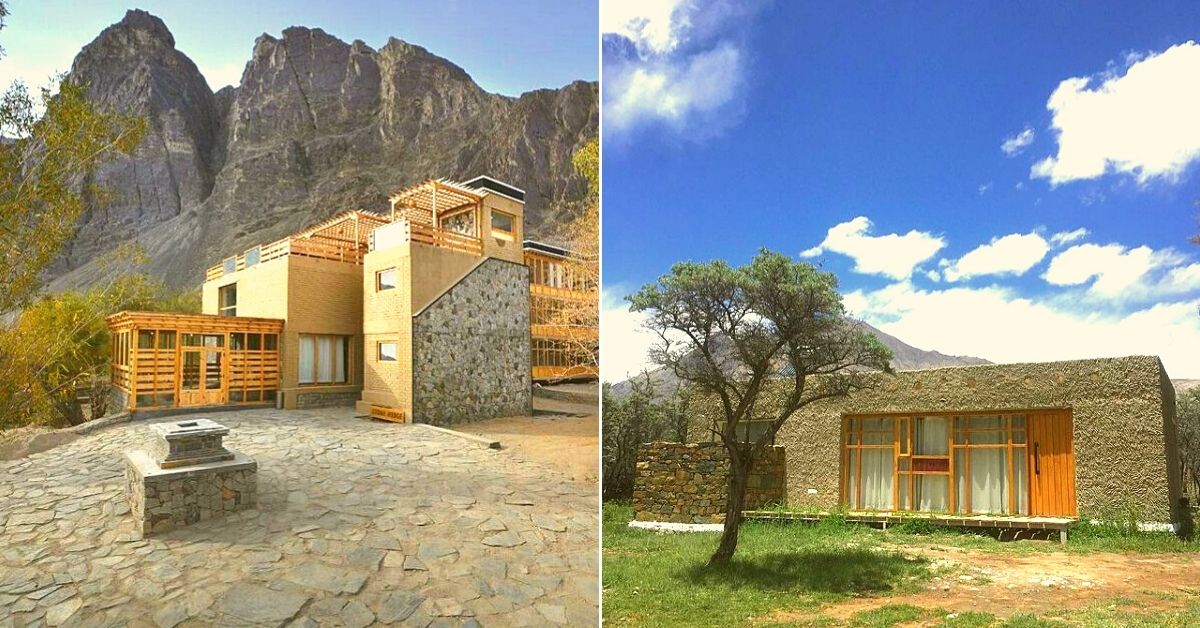

It has been more than seven years since he first came to Ladakh. Shuttling between Leh and Nubra, Earthling Ladakh has constructed eight natural buildings that include hotels, boutiques, restaurants and homes as well, while five are still under construction. He is also constructing his own home, studio and workshop space in Disket village, Nubra. He is also training and employing local Ladakhi masons and other artisans for a myriad of different projects in the region.

From Visakhapatnam to Ladakh, Via Assam

Born and raised in Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, Bogadhi studied at the prestigious School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) in New Delhi before entering the workforce. Despite regular stints with different architectural firms in Delhi and Bengaluru, he was tired of working out of studios, sitting in front of a computer and working with a fixed material palette highlighted by concrete. He was desperate for a change.

“While designing in a studio, there is a disconnect with the material that is eventually used to build a structure. It’s more like a modelling exercise we do on software. Once you move away from the city, the material palette suddenly changes, and that affects your design. This is why I wanted to move away from cities and work in more rural settings where the material and design you employ addresses the local context,” says Bogadhi, in an exclusive conversation with The Better India.

So, he quit city life in 2012. After a brief, yet unsuccessful stint in rural Assam, he received a call from one of his professors from SPA in 2013 to work on a project in Ladakh.

Located in Nimoo village, which lies about 30 km from Leh, Bogadhi and his professor were tasked with restoring a 100-year-old building and converting it into a boutique hotel. Called the Nimoo House project, they used locally available material like mud, stone and wood. Most of the material was sourced near the site.

Why The Past?

In Ladakh’s past, homes were predominantly made of materials like mud, stone and wood. But that past has largely been taken over by concrete jungles, particularly in Leh.

“Traditional Ladakhi houses won’t make sense if those traditions don’t really exist anymore. If people don’t live that pastoral lifestyle, I don’t understand why they would need a traditional Ladakhi home. Although I do refer to traditional practices, designs and source material locally, my architecture is more about adaptability to the requirements of today’s generation and the local ecology,” says Bogadhi.

“When it comes to Ladakh, there are a lot of houses which are dilapidated or unused. In response, people build new concrete houses. It’s important to understand that the old vernacular architecture of Ladakh was not flexible enough to change with the aspirations of people today. Their lifestyles have changed. It’s not like that the new generation doesn’t like the old buildings their grandparents lived in. They just don’t prefer living in them because their lifestyles have changed,” argues Bogadhi.

The ground floor design of traditional Ladakhi homes, where cattle and livestock were once stored, didn’t make sense nowadays. Going further, the pattern of having a winter kitchen on the first floor and summer kitchen on the second didn’t make sense because many residents don’t spend the winters there.

In Nimoo House, they added new components like a library instead. Architecture, he argues, is not just about being sustainable or organic, but also adaptable. In different homes, a particular space that families built 50 years ago may not be useful today. Still, an architect must be flexible enough to repurpose it instead of breaking the whole structure down.

Finding a Home in Ladakh

Once the project was over, his thoughts shifted to finding new work. Unfortunately, during his stint in Nimoo, he did not establish a social network that would have helped him line up a couple of more projects. But he couldn’t withstand the allure of staying back. In the following year, while looking for projects, he worked in a rafting company, doing rescue work.

After the summer of 2015, a few residents of Nubra who had heard about his work in Nimoo House approached him, and the rest, as they say, is history.

“The material palette in Ladakh is not very elaborate. Essentially, you have earth, wood (predominantly poplar and willow) and stone to work with that are available in different parts of Ladakh, but in different colours and forms. With a keen understanding of the principles of load-bearing, I found it very easy to rearrange these materials. More importantly, what really kept me in Ladakh was its stunning landscape. For an architect, when we construct a building in a city, it usually gets lost among other concrete structures. When I see the beautiful landscape in Ladakh, my challenge is to make a structure that complements it visually and ecologically,” notes Bogadhi.

Looking at his structures, one does notice that the colours and material fit the landscape well. That’s also the reason why he doesn’t take up projects in Leh town because that context of a beautiful landscape doesn’t quite exist and it has turned into a concrete jungle.

Natural Materials

In the Journal of Landscape Architecture, Bogadhi describes the materials he employs.

Earth is the base material across all the projects, since earth is the single, logical and obvious material available at every site, in fact everywhere on the planet. Often dug out from the site, and other soils are added from the proximity to get the desired mix. Stone is used as a complimenting material to earth, which brings contrast, and identity to the volume. Most of the stone is redundant from the road-building department who build extensively in Ladakh, being a border area. Flat stones are extensively used as hard, dry surfaces, pitched without any mortar. Wood is primarily used in roofs, just like in the traditional buildings in Ladakh. For every tree cut in the roof construction, we plant ten new trees of the same species in the site.

Why the emphasis on natural materials?

“My building should outlive me and future generations. That’s why I choose natural materials on the outside and inside. Although many traditional homes in Old Leh lie in ruins, you can see they’ve aged gracefully. These buildings have been truthfully made in terms of material and purpose. I don’t use concrete because it’s not durable. Buildings made of natural materials last longer, but only if they’re done with integrity and abide by the principles of construction. It’s not just about the material, but craftsmanship as well,” he says.

Most homes that Bogadhi works on take cognisance of the fact that Ladakh lies on the ‘High Damage Risk Zone’ of seismic zone IV. In other words, a region susceptible to earthquakes. In September, the region was struck by a series of low-intensity earthquakes.

This was something the older generations understood. In the old natural buildings, we observe wooden seismic bands along the outside walls.

“A ring beam, or seismic band, helps tie the walls [often made of mud or stone]. It is one of the essential components of earthquake resistance for load-bearing construction. It prevents the distortion or displacement of walls in the event of an earthquake. Timber lacing provides added tensile strength to the walls to prevent the development of vertical cracks,” notes researcher Bhawana Dandona in this 2006 paper for the University of Pennsylvania.

“I use the same technique in a modern way where the stone is much more handcrafted as compared to older times. We are looking back at tradition but also modifying it for the modern context. A lot of stress is given on refined craftsmanship. Once there is a certain edge in craft, an architect’s design can really appeal to a consumer’s aspirations,” argues Bogadhi.

Finding The Materials

Meanwhile, the material is sourced from the vicinity of the site only upto 1.5 km. By sourcing material from the immediate vicinity, a client’s home becomes unique in its own right. If someone wants to replicate this design elsewhere, it won’t make sense because that particular type of mud or stone isn’t available there.

Bogadhi also believes this means people don’t have to stress about making elaborate designs or buying expensive materials. This approach is beneficial for the architect and client as well.

“Today, a good quality earth building is 25% more expensive than a cement structure. This is due to the limited workforce acquainted with earth construction techniques. However, once earth construction becomes mainstream and scales up, the cost should be the same. Natural materials are reusable. In a way, an earth structure will always be cheaper in the long run, whereas once a concrete structure falls apart, you end up dumping the leftover material elsewhere. This adds to the garbage problem. With natural buildings, you can bring down the whole structure and rebuild it with the same material. These structures also have great insular properties, which is particularly important for Ladakhis, who experience extreme temperatures. Mud buildings, for example, heat up very slowly during the day and release heat into the room slowly at night,” observes Bogadhi.

Techniques and Tradition

Earthling Ladakh primarily employs rammed earth technique in their structures with a greater emphasis on craftsmanship. Bogadhi has three local Ladakhi masons who work with him, and all of them work hands-on. On occasions, they construct some walls mixing rammed earth with some wood or stone.

It’s not merely about the technique, but also the aesthetic quality. They also adopt random stone masonry or random rubble, which works well in high seismic zones. It has the flexibility to rearrange the parts within a structure during an earthquake.

What can young architects from Ladakh learn from tradition?

“There are some great things about tradition, like how they adapted to the local geography and climate. These buildings really adapted to the seasons, lifestyle and maintained a real balance with the immediate ecology. Settlements, for example, in this cold desert, grew around water sources. Today, there is very little concern about how your homes must adapt to the natural surroundings. People are building homes on flatlands far away from a water source. This is something young architects in Ladakh really need to understand and change. The region survived on the principle of adaptation. People mustn’t forget,” says Bogadhi.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167