This LGBTQ+ Champion Edited The Award-Winning ‘Satya’ When He Was Just 19!

“Apurva Asrani is actually not just a champion, but also one of the finest editing and screenplay minds in our country,” says legendary Bollywood actor Manoj Bajpayee.

The story of how Apurva Asrani (42), award-winning film editor and screenwriter, got his name is both interesting, and prophetic.

His parents first met at a cinema hall in Bengaluru in 1975 to watch the iconic Ramesh Sippy film Sholay. From thereon, they would meet discreetly at cinema halls since young couples back then couldn’t really date publicly.

Fast forward a few years later — Apurva’s mother was pregnant and his father, a cabin crew with Air India, met his hero and legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray, on one of his flights. Inspired by the encounter, he returned home and announced that he would name his unborn child after Apu, one of Ray’s most iconic characters from the ‘The Apu Trilogy’ — Pather Panchali (1955), Aparajito (1956) and The World of Apu (1959).

The duo was blessed with a son on 21 March 1978, and as decided, he was named Apurva.

Early Days & Satya

While his early school days were spent in Bengaluru, Apurva would eventually go on to study and live in Mumbai. It was in the city’s Jai Hind College, where he found a creative outlet.

Still in college, he got his first gig working as an assistant on the popular Bollywood countdown show BPL Oye! on Channel [V] in 1995. Picking up skills like video editing, he would soon graduate to doing promos for feature films.

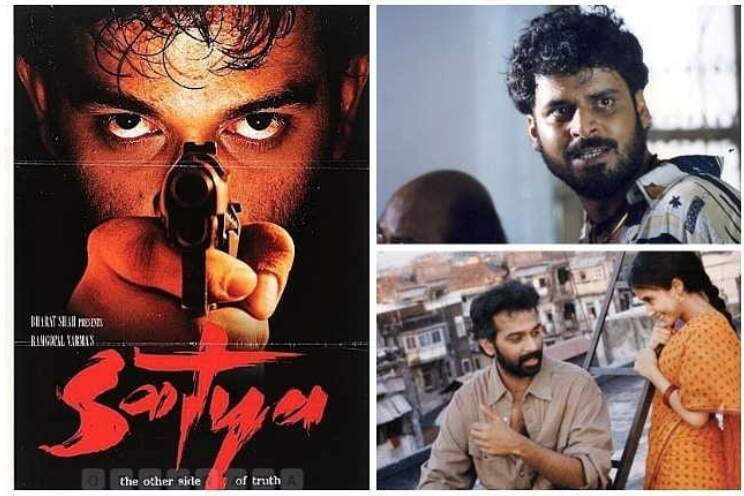

“One of the early promos I did was for a film directed by Ram Gopal Varma called Daud (1997). He was very happy with the way we had collaborated and that’s when he offered me the editing gig for Satya. I was only 19 at the time of editing Satya in 1997, but Ramu had a reputation for taking chances on fresh talent, and took a massive chance on me,” says Apurva.

With the exception of Urmila Matondkar and Paresh Rawal, who played a cameo, everyone working on the film was new and out to prove a point. Apurva recalls what it was like, working in an atmosphere that didn’t feel like it was being guided by old experienced hands.

“From Anurag Kashyap and Saurabh Shukla, who wrote the screenplay, to Manoj (Bajpayee) playing his first lead role as the iconic gangster Bhikhu Mhatre, a lot of people owe their careers to him. Even the music directors — Vishal Bharadwaj and Sandeep Chowta — weren’t well known then, and this resulted in a very charged atmosphere on set. Everyone working on the set was passionate and hungry to prove themselves. ” he recalls.

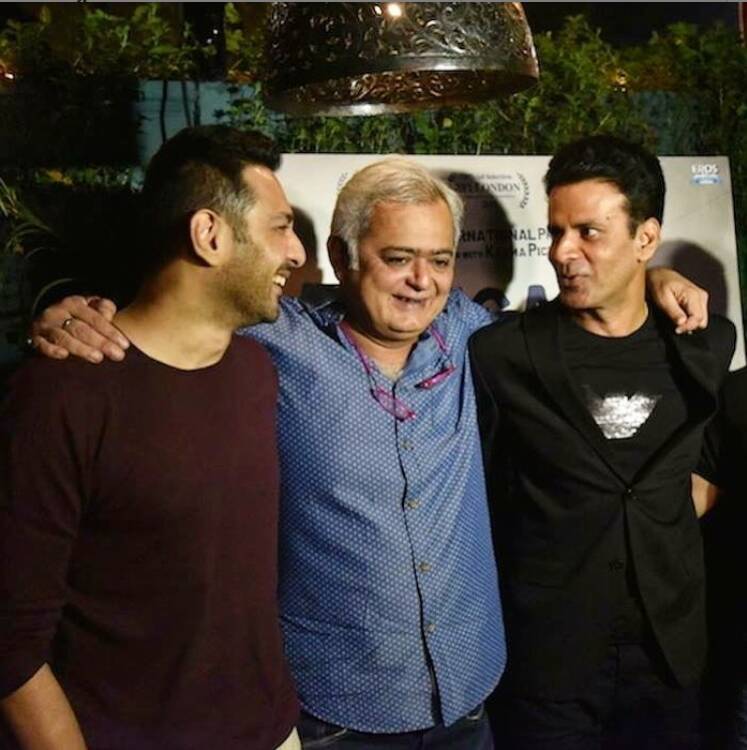

“I first met Apurva about 23 years back when he was editing for Satya. He was 19, intelligent and I was impressed by the fact that someone this young was editing such an ambitious film. I was quite curious to know him, understand him, where he was coming from and what Ramu saw in him. That’s how it all started,” recalls Manoj, speaking to TBI.

Editing Satya

During the shooting of Satya, which started sometime in August 1997, Mumbai was under the vice-like grip of the underworld which extended to the film industry. Gangsters would supposedly extort money or demand protection money from film producers.

On the first week of shooting Satya, Ram Gopal Varma’s friend and film producer Gulshan Kumar was shot dead for allegedly refusing to pay ‘protection money’. Apurva recalls how the incident shook everyone up on set, but also remembers that it completely changed the approach of filming Satya from that point onwards.

That change in approach came in one particular scene early on in the film when the gangster played by Sushant Singh, Pakya, comes to Satya and tries to extort money for the neighbourhood orchestra. Pakya even flashes a blade in front of Satya to threaten him.

“Instead of giving into his demands, Satya (JD Chakravarthy) takes the blade and slashes Pakya’s face, who falls to the floor with blood on his face screaming in agony. There is a horror in that shot which we hadn’t seen in earlier Bollywood gangster flicks. It reflected what everyone was feeling after the death of Gulshan Kumar,” he recalls.

The process of making the film was very organic. Scenes were literally being written on set and that organic process followed into the editing room. Since Apurva was seeing the process play out on the set, he didn’t follow a very regimented approach to editing the film. In the edit room, both Ram Gopal Varma and him would play around with how the scenes were constructed. Take the example of how the film opens.

The opening monologue of the film was a complete creation of the editing room with a voiceover talking about how Mumbai never sleeps, the class disparity and the underworld.

Aside from Ram Gopal Varma, who gave him a free hand, there were stalwarts like Gulzaar, who wrote the lyrics to Satya, and ace filmmaker Shekhar Kapur, who would watch the edited footage and give their valuable feedback. Working in their presence and taking their feedback really guided how the Satya team approached the film.

The Craft of Editing a Film

In a glowing article about Satya on the 20th anniversary of its release, film critic, Sukanya Verma writes, “Shot in a blue-brown palette, the clever compositions — a mix of cool camera angles, hand-held view, long shots and noir lighting — capture the stifling complexity and conflicting emotions of its characters.”

Most film reviews are predominantly focussed on the actors, directors, cinematographers and music, of course. Despite its centrality to the filmmaking process, there is barely a line or two about the editing process, and it’s usually about how it determines the pace of a film.

“The pace of a film is just one element of editing. According to me, the editing table is where the film is actually made. What comes into the editing room is hours of footage ranging from 8 to 10. There have been films, where I worked with nearly 14-15 hours of footage. You have several scenes that make up a film ranging from 80-100. Each scene is divided into shots. Each shot is filmed several times till the director gets a satisfactory take. Each shot will have a minimum of 4 takes or sometimes 25 depending on what is achieved,” says Apurva.

What the editor first does is start to assemble the scene. To assemble the scene, they have to choose takes with the right moment, expression or tone of the actor. They (the film editor) have to take into consideration what character has to be maintained through the film.

Right from the word go, they’re sifting through hours of footage and are heavily invested in the story and characters. They have to choose the best of elements like the actor’s correct tone, performance, lighting, camera work and direction from one particular take and sometimes compromise on one aspect to highlight the other.

“These are choices editors make. Then you construct the scene and have the choice to say, I would like to open the scene with a close up even though I have this master shot of everyone sitting in a room. I’ll begin with a close up of a character, and slowly reveal the other characters in the room one by one. You can also edit out dialogues or lines that are not necessary. Sometimes, you get rid of entire scenes because it’s overstating something. A film too verbose can be sometimes hailed as an understated one because of the editor’s call. It’s in our hands how to construct a scene. Out of 10 shots, as an editor, I can just take one shot on a single take because the actor has held it so well. When the scenes are ready, you put them together and construct a film,” informs Apurva.

From Script to Screen

One can edit a film rooted in the script or a film can evolve from a script like Satya, Snip (2000), the Indian English gangster film which won Apurva and collaborator Suresh Pai a National Award, Chhal (2002) or Shahid (2012), a film about a real-life human-rights and criminal lawyer starring Rajkummar Rao and directed by Hansal Mehta.

For example, a film like Shahid, the written script begins and ends very differently from what you see on the screen. The screenplay was non-linear, and when the director Hansal Mehta first showed the film to his peers, many weren’t moved by it emotionally.

“I took the call to make the film more linear, which was a challenge because it wasn’t shot that way. To open with protagonist Shahid Azmi’s death, which many would say is giving away the ending, is a choice the editor makes saying this film is not a mystery thriller. This film is trying to evoke a very different reaction from the people. It’s not about whether Shahid died or not, but about why did he die, how did he die and what was his life about. It changed the whole focus of the screenplay. If a film communicates a compelling story, and it’s a gripping narrative, I think the editor has done a good job,” says Apurva.

Hansal Mehta, the director of Shahid, had this to say about Apurva’s contribution to its screenplay in an interview to India Today just after the film’s release.

“We first wrote a complete linear draft of the script. I showed it to actors and stars and they found it too long, boring and simple. Another writer asked me to make it more convoluted so we then wrote a non-linear draft. We shot that draft but in sequence. Then I took it for editing to Apurva Asrani. He is an old collaborator. I got him back from a self-imposed exile in Bangalore. He took my material and said, ‘Give me some time with it.’ We initially tried to make a non-linear cut. Apurva was like, ‘This is not working. Let me cut the film and line-up the story. Let’s communicate it as simply as possible.’ He shaped the narrative and that’s why I have given him a screenplay credit too,” says Hansal.

“Editing is one of the most important aspects of filmmaking. Depending on how an editor sees the film content, they can either make or break it. They must have an in-depth understanding of storytelling, the narrative, shots, all the technicalities of cinema, performances, beats and rhythms. A director must have an editor’s sense while making a film and an editor must have a director’s sense of filmmaking while editing. Apurva showed a lot of promise in the beginning, and has gone on to do great things since. He has received his share of accolades. Seeing his success, everybody has realised how right Ramu was to take a chance on him,” says Manoj.

Apurva has also gone beyond the film medium and edited four episodes of the web series ‘Made in Heaven.’ He was brought in by filmmaker Zoya Akhtar and writer-producer Nitya Mehra because they were creating a gay protagonist that hadn’t really been done before.

“They wanted me on the editing team to ensure they got the tonality of the gay man right. Working with Zoya was extremely challenging, as she is an extremely astute filmmaker, but it was truly gratifying as well. The fundamental difference between working in films and web series is that in the latter you have 8 to 10 episodes to go into details. Working on a web series is very liberating. When we want to explore characters, parallel characters, sub plots, you have very little wiggle room in films. In a web series, you can paint a very composite picture showing the different layers, sub-plots, delve into them and come back to where you want it to be without making it look like a digression. I genuinely think that they are the future of storytelling,” he says.

Apurva has even written two web series. One is almost completely shot. It is a courtroom drama about the role of the woman in Indian society and will be out on a major OTT platform very soon, says Apurva.

Aligarh & LGBTQ+ Rights

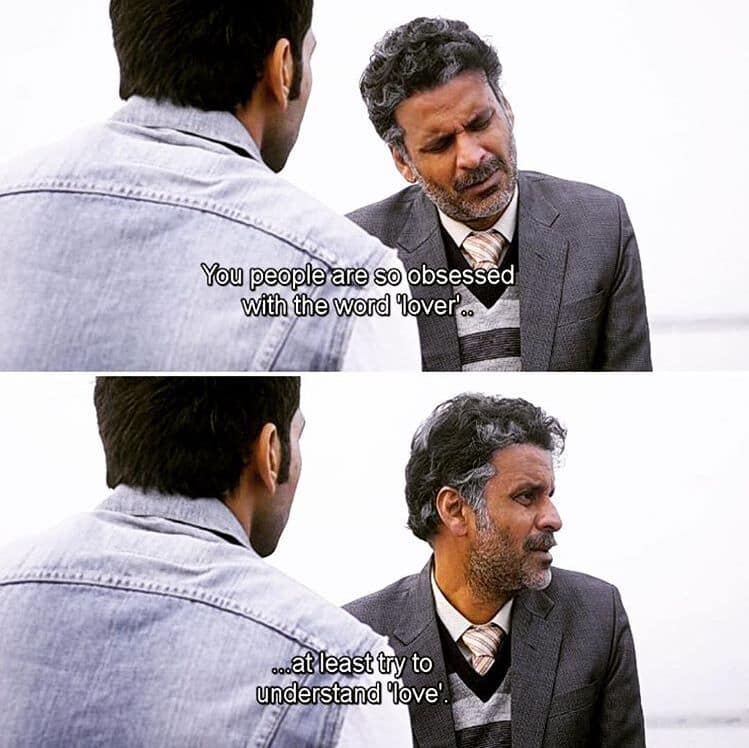

It’s safe to suggest that Aligarh (2015) is probably his most significant project till date. The Hansal Mehta-directed film about a professor, played by Manoj, who is outed for being gay and thrown out of Aligarh University, is where Apurva made his debut as full-fledged screenwriter, while also editing the film.

“As a gay man, I wanted to write dialogues for a character who isn’t defined by labels or the ideas that the world has thrust upon us. Thankfully, I had Manoj, who made whatever I wrote even better on screen by improvising and adding stuff to it, which is what great actors like him do. He made me look very good in Aligarh as a writer. Manoj was a lead actor in my first film as an editor, as an screenwriter and will star in my directorial debut as well which is being pre-produced,” informs Apurva.

“I hope he finishes that movie soon. He’s quite the perfectionist,” quips Manoj.

Coming back to Aligarh, what Apurva was soon faced with is a conflict of interest that exists between screenwriter and editor. As an editor, he follows a certain principle.

“When I look at the rushes (a film production term used to describe raw footage from a day’s shooting), that’s the script. Whenever I receive the footage, what was written in the original script becomes somewhat less important because it evolves when shot in front of a camera. An actor brings something to the performance, the director has his moments of magic on set or bad weather forces you to shoot indoors. A bad actor forces you to reject a scene or a great actor makes a terrible scene wonderful. As an editor, your rushes are your script and not necessarily the written word,” notes Apurva.

When it came to Aligarh, he admits to having his ego hurt when the footage came through considering there were several changes from his original script. He was trying to hold onto his script because it’s the first ever he had written and that it needed to come out right.

“I had a fight going in my head donning the role of both screenwriter and editor. Hansal saw this struggle, asked me to take a break and get refreshed. Even though I asked Hansal to get someone else to edit it, he refused. During my break from Aligarh, I edited ‘Waiting’ directed by Anu Menon starring Kalki Koechelin and Naseeruddin Shah. This was completely different to Aligarh in terms of style, performance and filmmaking. When I finished that project, I felt ready to edit Aligarh. So, I came back to Aligarh purely as an editor and never referred to my written script,” he recalls.

Plus with filmmaking, there is so much evolution and interpretation in every single process. If one is going to be rigid about an earlier interpretation, it stops the growth of the film.

“Manoj’s performance will be counted among the best portrayals of a gay character. As for getting them to interpret the characters, Apurva’s script deserves credit for that. It provided enough information for the actors to take cues from. A professional actor soaks up everything and then interprets the material and brings his performance,” says Hansal Mehta in an interview with Scroll.in in October 2015.

Going beyond the process of making it, the promotion for Aligarh saw Apurva coming out publicly as a gay man and donning the role of an advocate for LGBTQ rights.

“When we were promoting Aligarh, I was on Barkha Dutt’s show on NDTV. It was a live show. Hansal, Manoj and myself were there. I hadn’t publicly come out as a gay man at that point in time although it’s not like I have ever hidden it. On the show, we were talking about the protagonist Professor SR Siras and what he went through. I almost found myself talking about him like the other straight people on the panel. Despite their best intentions, I felt it would carry so much more weight if a gay man said it. Everything I wrote in Aligarh, it genuinely came from my own struggle as a gay man. I felt that it was hypocrisy to conceal that fact. Instead of holding back, I came out,” he recalls.

Since Aligarh released, followed by Made in Heaven a couple of years later, many struggling to come out to their loved ones have reached out to Apurva. Even in an interview with Bombay Times in 2018, he spoke of how his parents really struggled with him coming out to them at the age of 20, although things have vastly improved since.

Today, he lives with his partner, Siddhant, in a house they bought in Goa.

For 13 years we pretended to be cousins so we could rent a home together. We were told ‘keep curtains drawn so neighbors don’t know ‘what’ you are’. We recently bought our own home. Now we voluntarily tell neighbors we are partners ?. It’s time LGBTQ families are normalised too. pic.twitter.com/kZ9t9Wnc7i

— Apurva (@Apurvasrani) May 29, 2020

“In the early days, my first impressions of him were of a man who was intelligent, but not very comfortable with the situation he was going through. There was a lot of conflict in his life. He was desperate to come out, express his own homosexual identity and be counted as someone for his ability more than anything else. Apruva’s existence and his own being also proves a fact I have always believed in that sexuality doesn’t determine the ability of the person. In my mind, Apurva is not only a champion of the LGBTQ movement in India, but also one of the finest editing and screenplay minds in our country,” recalls Manoj.

Apurva, meanwhile, talks about how there is an appearance of social progress in the film industry, but very few are out of the closet. “There are so many actors, filmmakers and media people who are gay in the industry, and and working very hard to hide their truth. I know because they have made passes at me. If you don’t respond favourably to their overtures you could get blacklisted, or canards could be spread about you in blind items,” he says.

But he stresses that he doesn’t have any time for all that negativity.

“There are far more people who are accepting of who I am in this world, which is why I have been able to come this far.”

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167