What Defines 2019? How About a 1950 Debate on National Language That Unites Us

It comes as no surprise that members of the Constituent Assembly—the framers of our Constitution—held fierce debates on the subject of language.

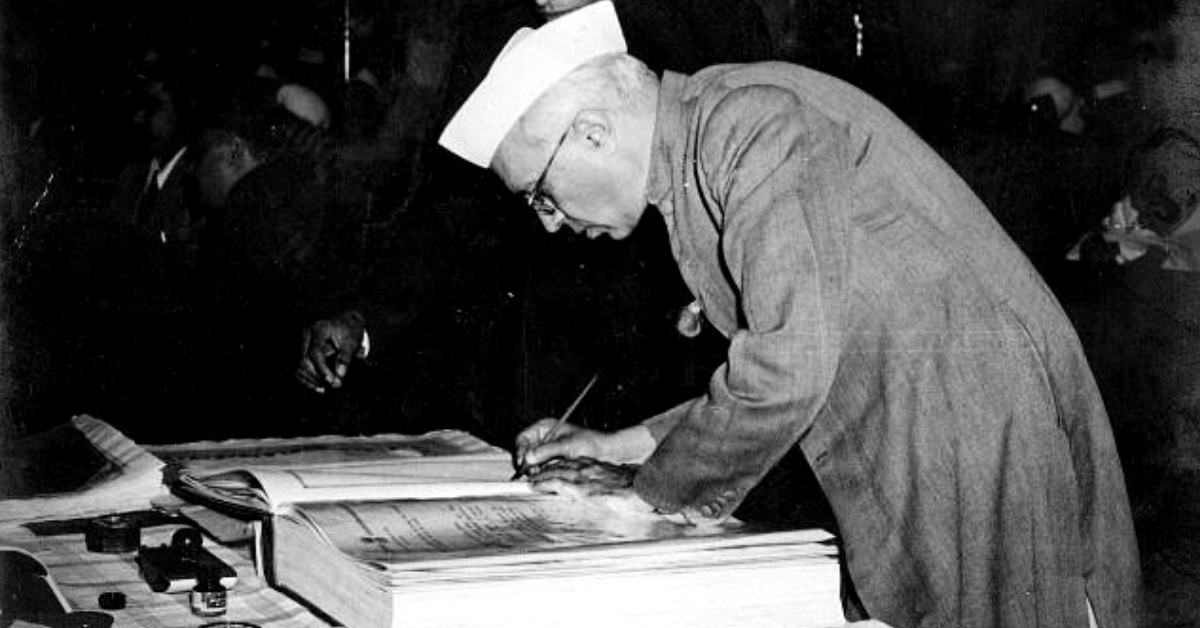

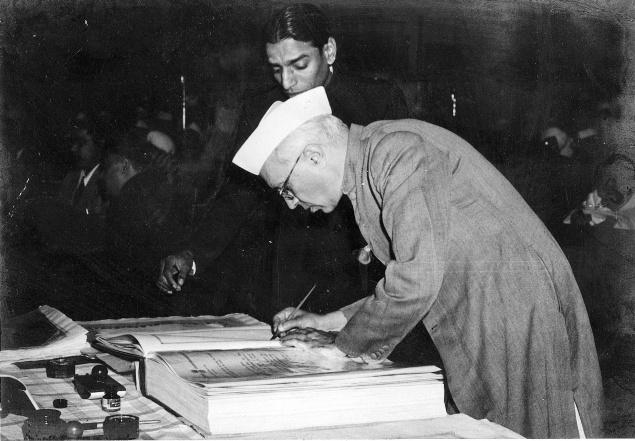

72 years ago, this week, 284 elected members of independent India ceremonially signed a magisterial hand-written tome. They were putting the final touches – literally – on a document they hoped would define India’s destiny.

Today, we can barely imagine the sense of infinite possibilities that fueled the five years it took to frame that document.

No matter how radical, liberal, conservative or outright unbelievable an idea was, if the majority of an Assembly of just 299 voted for it – It could happen! So to a large part, who we are today is who they wanted us to be.

Join The Better India in this four-part series ‘Constituent’, as we explore a simple question – What did 1950 feel 2019 would be?

Part four of the series takes a look at one concept – Language.

Who are you?

Where are you from?

Where do you live?

These are questions that all of us face whether we are at a job interview, filling out an application form or even when we meet someone new.

They are aimed at ascertaining your identity, and one of its most distinct markers is language—the lens through which we see the world.

Thus, it comes as no surprise that members of the Constituent Assembly held fierce debates on the subject.

What language should members employ when addressing the House? What language should the Constitution adopt? What will the national language of this country be?

These are some of the critical questions they addressed in the course of their debates.

On December 10, 1946, the first day of business, RV Dhulekar, a representative of the then United Provinces, addressed the House in Hindustani while moving an amendment. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had described Hindustani as the “golden mean” between Hindi and Urdu.

Dr Sachchidananda Sinha, the then Chairman of the Constituent Assembly, interjected and told Dhulekar in no uncertain terms that many members of the House didn’t understand Hindustani.

“People who do not know Hindustani have no right to stay in India. People who are present in this House to fashion a Constitution for India and do not know Hindustani are not worthy to be members of this Assembly. They had better leave,” said Dhulekar in response.

He added that the Procedure Committee of the House must frame the rules, not in English, but Hindustani.

“As an Indian, I appeal that we, who are out to win freedom for our country and are fighting for it should think and speak in our own language. We have all along been talking of America, Japan, Germany, Switzerland and House of Commons. It has given me a headache. I wonder why Indians do not speak in their own language. As an Indian, I feel that the proceedings of the House should be conducted in Hindustani. We are not concerned with the history of the world. We have the history of our own country of millions of past years,” said Dhulekar.

Suffice it to say, there was pandemonium in the House, and this wasn’t to be the last time the issue would raise its head.

During one session, a member demanded that all car number plates in English must be replaced with Hindi. Another member wanted the official version of the Constitution to be written in Hindi, with the unofficial version in English.

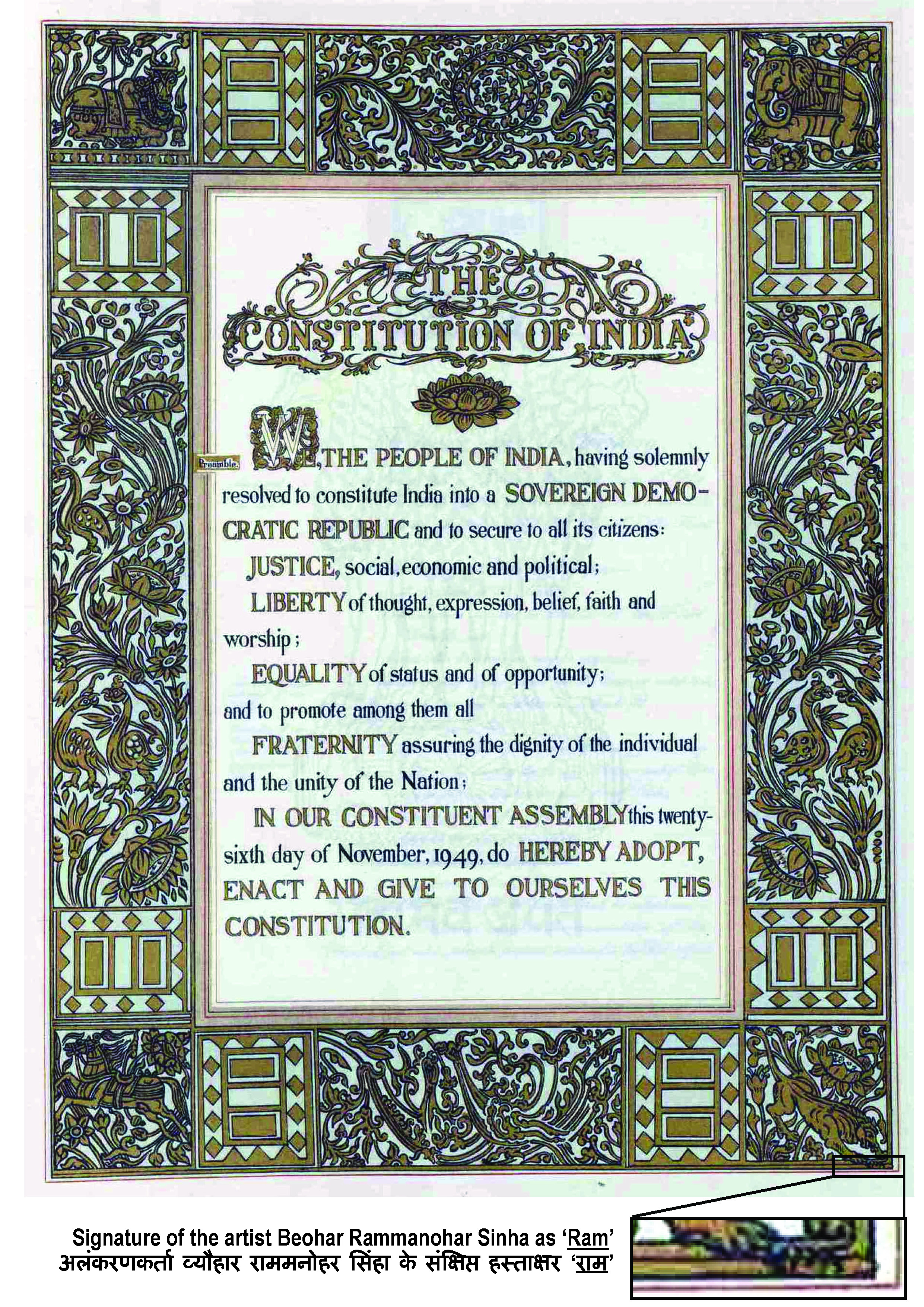

The latter demand was rejected by the Drafting Committee led by Dr BR Ambedkar, who argued that English would better and more accurately capture the technical and legal terms articulated in the Constitution.

However, for many members particularly from the Northern regions where Hindi is spoken extensively, the proposition of adopting a Constitution written in English was “insulting.”

One must understand these contestations in light of the British colonial rule, where English was the lingua franca for both the dispensing of administrative responsibilities and learning in institutions of higher education.

With Independence, many freedom fighters saw the need to rid the country of English, the language of the colonialists.

This was their way of breaking the chains of colonialism.

“In my opinion, Hindi alone can be the national language of this country. I think there are only a few members of this House who believe today that English can be made the national language of this country. The Hindi-Hindustani controversy has also come to an end, simply because Article 99 of the Constitution refers to ‘Hindi or English’ alone in relation to the transaction of business in our Parliament. Thus, the question of Hindustani also exists no more.

As far as the members and residents of South India are concerned, I would agree that business here may be conducted in English also for some years to come. We should not impose anything on them. But Hindi must be our national language and Devanagari our national script,” said Seth Govind Das, a member elected from the Central Provinces and Berar, on November 5, 1948.

But what language could this intensely diverse country with a multitude of tongues adopt?

Well, there were the likes of Nehru and even Mahatma Gandhi, who wanted to adopt ‘Hindustani.’ However, Partition destroyed any chance of a consensus towards Hindustani. From the ashes of Partition, the members from the North began to vigorously push for a version of Hindi dipped in its Sanskrit roots.

But what about their colleagues from the South?

Dr BR Ambedkar said in one of his speeches at the Assembly:

“One language can unite people. Two languages are sure to divide people. This is an inexorable law. Culture is conserved by language. Since Indians wish to unite and develop a common culture, it is bounden duty of all Indians to own up Hindi as their official language.”

Then there were the likes of LK Maitra, who advocated for the recognition of regional languages at the State level and that “the chosen national language should not be made exclusive.”

“There were others like Lokamanya Tilak, Gandhiji, C Rajagopalachari, Subhash Bose and Sardar Patel who demanded that Hindi should be used throughout India without any exceptions and the states should also resort to the use of Hindi language because it would promote integration,” writes Priya Misra, Assistant Professor at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore.

Probably, no one quite captured the dilemmas before non-Hindi speakers like TT Krishnamachari, elected from Madras, who on the same day said:

“We disliked the English language in the past. I disliked it because I was forced to learn Shakespeare and Milton, for which I had no taste at all… [I]f we are going to be compelled to learn Hindi… I would perhaps not be able to do it because of my age, and perhaps I would not be willing to do it because of the amount of constraint you put on me. … This kind of intolerance makes us fear that the strong Centre which we need, a strong Centre which is necessary will also mean the enslavement of people who do not speak the language of the Centre. I would, Sir, convey a warning on behalf of people of the South for the reason that there are already elements in South India who want separation…., and my honourable friends in U. P. do not help us in any way by flogging their idea [of] “Hindi Imperialism” to the maximum extent possible. Sir, it is up to my friends in U. P. to have a whole-India; it is up to them to have a Hindi-India. The choice is theirs….” (Source: India After Gandhi, Ramachandra Guha)

So, what the Constituent Assembly was left with was one side which supported the cause for Hindi as the official, while the other didn’t. The Assembly was split in half.

Eventually, both sides came to a compromise with members KM Munshi and Dr NG Ayyangar proposing a solution.

“English was to continue as the official language of India along with Hindi for fifteen years, but the limit was elastic, and the power of extension was given to the Parliament,” writes Priya Misra.

But for “fifteen years from the commencement of the Constitution, the English language shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union for which it was being used immediately before such commencement.”

Under the Munshi-Ayyangar formula, all official proceedings of the courts, public services and the all-India civil services would be conducted in English until 1965.

Following the adoption of the Constitution, however, multiple language-driven movements began springing up across the country, particularly in states like Andhra Pradesh.

In 1956, the Parliament passed the States Reorganisation Act, which espoused the organisation of states along linguistic lines.

Moreover, as the 15-year period was about to lapse, the Government of India under Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shashtri sought to impose Hindi—a move vehemently rejected by the Southern states, particularly Tamil Nadu.

Also Read: CN Annadurai: Karunanidhi’s Mentor & Tamil Nadu’s First Political Stalwart

The rest, as they say, is history.

Today, the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution lists 22 official languages of the Republic of India. With a myriad of regional interests constantly seeking a more significant stake in this country’s democratic polity, there are demands to add more languages to the Eighth Schedule.

There are two ways in which one can view the language debate, which first began in the Constituent Assembly.

One, it fomented regional differences that have possibly come in the way of building a unified nation.

However, the other view suggests that the language debates helped the real power brokers in Delhi acknowledge the innate diversity of this country.

That acknowledgement, some would argue, helped foster a better sense of unity, which recognised and respected this diversity.

What do you think?

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167