Horrified by The Cruelty of War, Emperor Ashoka Built an Infrastructure of Goodness

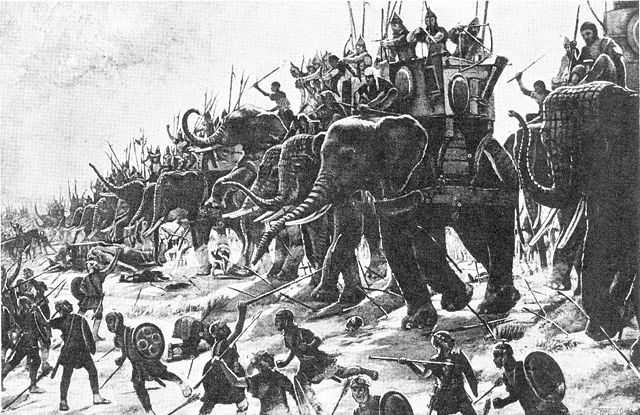

Mauryan emperor Ashoka reigned over one of the largest, most cosmopolitan and most powerful empires in South Asia. His visionary values and adminstrative genius would have remained unknown if not for the discovery of the Ashokan rock edicts.

“Amidst the tens of thousands of names of monarchs that crowd the columns of history … the name of Ashoka shines, and shines almost alone, a star.” – HG Wells, English novelist, journalist, sociologist, and historian.

On a large grey boulder in Pakistan’s windswept Khyber valley, few words are inscribed for posterity: ‘Doing good is hard – Even beginning to do good is hard.’

These powerful words belong to the third Mauryan emperor Ashoka who reigned over one of the largest, most cosmopolitan and most powerful empires in South Asia. Over the years, he has come to be remembered as one of the most exemplary rulers in world history because of his geographical conquests and the messages of tolerance that he spread throughout his sprawling empire.

These visionary values, humanitarian ethics, even the administrative genius of emperor Ashoka would have remained unknown if not for the discovery of the Ashokan edicts in the 19th century.

Until 1837, when Orientalist scholar James Princep deciphered these edicts, Ashoka was just another ancient Indian emperor. Understanding his inscriptions changed it all.

Interestingly, when the edicts began to be deciphered by Princep, nobody knew who the author was. Because the first inscription did not mention Ashoka, it spoke of ‘Piyadasi’ (Beloved of the Gods).

It took more than seven decades for the world to understand that Ashoka was Piyadasi. This was made possible by the discovery of another inscription in 1915 in which the Emperor addressed himself as ‘Ashoka Piyadasi’.

While many such rock faces have eroded, Ashoka’s message can still be found on rocks across India – all along the frontiers of his empire, from Khyber Pass to South India.

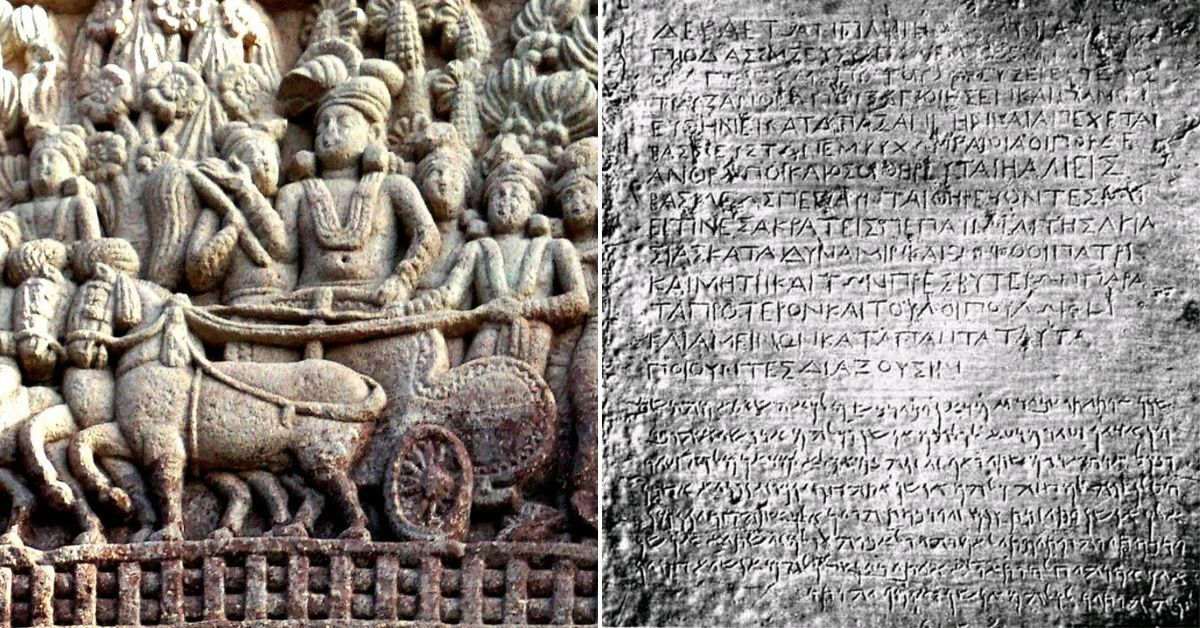

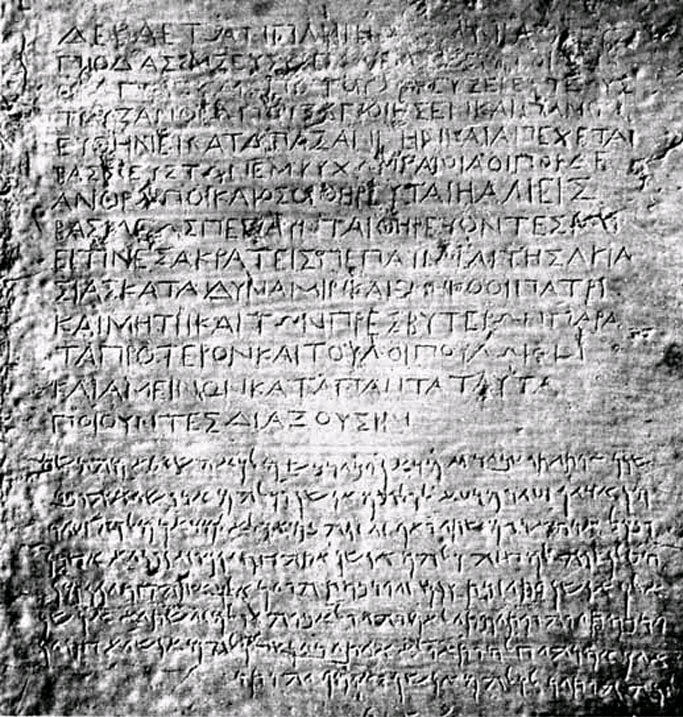

To understand Ashoka’s messages, we need to trace the incredible story of transformation behind them — a story that begins in 270 BC, eight years after Ashoka came to power. In his first war after accession, Ashoka invaded Kalinga, an independent feudal kingdom located on the east coast (covering present-day Odisha and northern Andhra Pradesh).

The victory left him with an empire larger than any of his predecessors, but it came at a considerable cost. According to historical accounts, the Kalinga was one of the deadliest battles in Indian history, claiming 100,000 and 300,000 lives.

Witnessing the bloodbath and the massive suffering that followed took a tremendous emotional toll on Ashoka. Renouncing military conquest and violence, the anguished emperor wrote in Rock Edict 13 that he was ‘deeply pained by the killing, dying, and deportation of captives that take place when an unconquered country is conquered.”

He gave up the predatory foreign policy that had characterised the Mauryan empire up till then and replaced it with a policy of peaceful co-existence. In his own memorable words inscribed on the 4th edict, Ashoka says that with his reign ‘the sound of the drums of war has been replaced by the sound of ethics’.

A transformed Ashoka decided to share his new outlook on life through messages carved into freestanding rocks and giant stone pillars located around this empire and along busy trade routes. He wanted his words to inspire people across generations.

At the end of the 5th rock edict, Ashoka says, “This inscription on ethics has been written in stone so that it might endure long and that my descendants might act in conformity with it.”

He also wanted them to inspire people from different regions and communities. This is why his edicts are no more restricted to a particular language than they are to a single place. Ashoka’s messages were not written in Sanskrit (the official language) but in vernacular dialects like Brahmi and Kharoshti so that they could be widely understood.

For example, an Ashokan edict near modern-day Kandahar in Afghanistan is written in Greek and Aramaic — it was an area that had once been under the control of Alexander the Great.

Source: Wikipedia

Through his edicts, Ashoka also promoted a policy of mutual respect and tolerance for people of different faiths. In his 7th edict, he says, “the king desires that all traditions should reside everywhere’.

In his 11th edict, Ashoka declares that goodness includes obligations to those who are socially beneath us, and to those with whom we are social equals. Thus, he says, we owe ‘respect to slaves and servants, and liberality to friends and acquaintances’.

In the 12th edict, he says, “One should listen to and respect all doctrines professed by others. [The king] desires that all should be well-learned in the good doctrines of other traditions.”

However, he was not a ruler concerned only with spiritual and philanthropic ethics. Efficiently managing the empire via centralised government from the Mauryan capital at Pataliputra, he showed how public infrastructure and governance, too, can be ethical concerns.

Ashoka’s public works include building excellent roads connecting key trade centres, planting trees along them to give shade, establishing mango groves, botanical pharmacies, rest houses, and even hospitals for humans and animals alike. To ensure that these initiatives were carried out, Ashoka went on frequent inspection tours and expected his bureaucrats to do the same.

Source: Wikipedia

Post-Kalinga, he also became an ardent supporter of forest and wildlife conservation.

As he outlined in the 2nd rock edict and the 7th pillar edict:

“Wherever medical herbs suitable for humans or animals are not available, I have had them imported and grown. I have planted mango groves, and I have had ponds dug up and shelters erected along the roads every eight kilometres. I have had banyan trees planted on the roads to give shade to man and beast. Everywhere, I have had wells dug for the benefit of man and beast.”

In ancient India, wild animals were considered the property of the emperor. Ashoka banned royal hunting parties and animal sacrifices at a time when these were the norm. Forest and wildlife reserves were established, and cruelty to domestic animals was prohibited.

Then he took the process one step further. In an act unmatched by even the most progressive modern states, Ashoka established free veterinary hospitals and dispensaries. Fa Hien, the Chinese traveller who came to India during the reign of Chandragupta II, has written about veterinary hospitals in Pataliputra, which were probably the first in the world.

Even today, his legacy of responsible statehood, tolerance and kindness remains carved into India’s rocks. It is thus perhaps fitting that an independent India adopted an Ashokan emblem – the Ashok Chakra– for its new flag. Modern India would do well to remember this ancient Indian emperor’s vision of a humane society.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167