Every day, at 7 o’clock sharp in the morning, the radio player at Niloufer Mavalvala’s home would be switched on, and the sounds of BBC’s morning broadcast would echo through the house, signaling the start of the day.

Soon, a steaming cup of tea would would make its way to the table, right beside the seat where her father would be quietly poring over the newspaper.

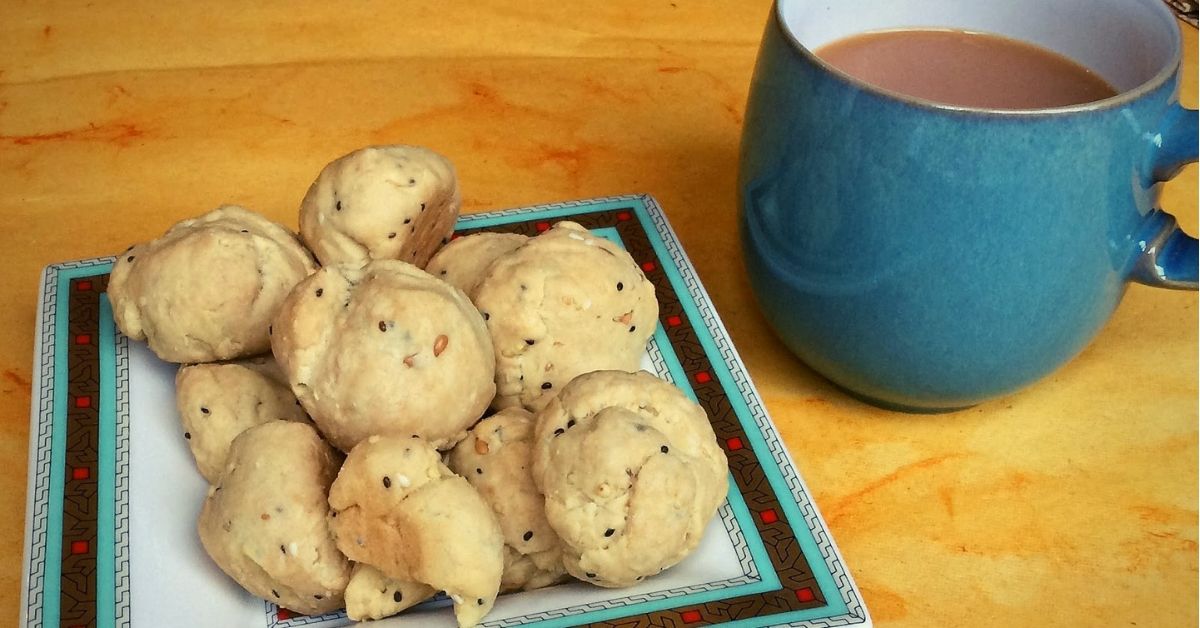

With a rising restlessness, she would hurry and make herself comfortable near him, and moments later, the much-awaited morning treat—a plate full of round, fawn-coloured biscuits—would arrive.

These were soon dunked into the cup of hot piping tea by father and daughter and gulped in unison.

The memory of this ritual, where Niloufer and her father together would relish these Parsi biscuits called Batasas and its crispy bite followed by the taste of melting ghee in the mouth is etched in her mind forever. She recounts it as one of the happiest moments of her life.

“For years, my father and I continued this ritual until he passed away when I was just 28 and pregnant with my first child. We were very close, and I was the special one to share the morning tea and biscuits with him. Today, although he is not there anymore, the biscuits coated in such sweet memories keep me company every morning,” shares Niloufer, a Parsi culinary expert and author of two unique cooking books.

In her book, ‘The Art of Parsi Cooking’, she shares a fascinating story of its origin and how the delicious Batasas were a product of reuse.

“As the Dutch colonisers left the shores of the Indian port city of Surat in the 1700s, a flourishing bakery was handed over to a local employee named Faramji Dotivala. This baker continued to produce loaves of bread for the local British – the next set of colonisers. Once the Brits too lessened in numbers, the popularity of the bakery diminished, and the wasted loaves were soon distributed to the local poor. Having the advantage of being fermented with an ingredient called toddy (palm wine), there was little chance of the bread ever catching fungus, prolonging the life of this staple yet making it harder in texture and more difficult to eat,” she explains, while emphasising on its longevity.

Soon local doctors began to suggest the stale bread as a convalescent food to patients, especially because it was easy to digest and would keep their stomachs full for long.

As its demand rose, Dotivala began to produce smaller specially dried bread buns for this purpose, which eventually led to the creation of ‘batasas,’ the simple bread-turned-biscuit made of just three ingredients— toddy, flour and water. With tides of time, the Batasa changed to a richer version with an addition of butter and or ghee (clarified butter).

It was a hit, and its popularity gathered such incredible momentum, that it is now considered to be among the most precious vestiges of Parsi cuisine.

Cities like Surat, Navsari and Pune slowly became strongholds of Batasas, all making varied claims on its origin. Although dwindling now, one can still find them in Irani Tea Houses across Mumbai and Pune.

“Batasas can be endlessly customised—they can be crisp, soft or flaky. There is also an amazing cheese batasa now popular among Canadians. You can have them plain or add in cumin, caraway seeds or toasted slivered almonds. Only the shape continues to be mainly round like the original buns!” adds Niloufer.

With a legacy of culinary marvels and decades of experience in baking, Niloufer realised her calling to contribute to the preservation of such an ancient cuisine.

So, she finally started her blog, Niloufer’s Kitchen, in 2013, which soon transformed into more than 10 books and e-cookbooks.

Revisit the unique taste of these ancient biscuits with a modern twist, and check out this special Multi-Seed Batasa recipe exclusively introduced by Noloufer’s kitchen for a healthy and tasty take on super grains.

Multi-Seed Batasa

4 cups sifted all-purpose flour

1 tbsp semolina

3 tsp baking powder

1 1/2 tsp salt

1 cup soft butter 8 ozs/ 226gms

8 tbsp water

Optional: For Multi-Seed “super grain” batasas add any of the following (a total of 50 gm by weight)

2 tsp hemp seeds 2 tsp chia seeds

2 tsp white sesame

2 tsp golden flax

2 tsp golden millet

2 tsp golden cornmeal

Process

In a bowl mix the dry ingredients. Add the softened butter in little pieces.

With the tip of your fingers crumble the mixture till it resembles little beads.

You can alternately use two butter knives or place all of it in a food processor using the pulse button.

Add the water one tbsp at a time until it all comes together. Remember to not over knead.

Roll out the dough into a long even cylinder on a lightly dusted floured surface.

Cut it into 48-60 pieces.

Roll each one very lightly into a ball. Place this on a baking sheet.

Preheat the oven to 325F/165C. Cook for 30 minutes.

Lower the temperature to 275F/135C and cook for 30 minutes.

Now lower the oven temperature to 225F/105C and cook until it cooks and dries from the inside, which will be another hour.

Leave to cool and store in an airtight box.

Tips

If you have a cake beater use the ‘k beater’ attachment to mix, if you have a food processor, it will take 5 to 10 minutes to put this together.

The dough should be soft to touch and smooth all over— very similar to the chapati/rotli dough.

Overturn cut into 2 or 4 equal pieces and work with one at a time. It is more even and quicker.

Keep the baking trays ready with greaseproof/parchment paper or lightly grease the tray with butter. You will need two large cookie sheets to fit all of them.

The trick is to dry the batasas from the inside, and so the heat variation is very important.

Batasas should have a light pink colour and not be white.

Try to keep them all even.

If you are not making the plain or Multi-Seed variety you may add the following:

2 ozs toasted slivered peeled almonds

1 tsp cardamom powder

2 tsp caraway or cumin seeds

1/2 cup almond powder or almond flour substituting for 1/2 cup of the flour

There are plenty of recipes with a bit of yeast added, which gives them a definitive aroma, texture and taste. However, this is a personal preference.

Also Read: King of Lemons: How the Gondhoraj Lebu Literally Remains True to Its Roots!

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: contact@thebetterindia.com

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?