Judges Appointment: What is The Collegium And Why is it Causing so Much Debate?

The recent impasse between the Supreme Court and Centre over the elevation of Justice KM Joseph has once again brought the collegium system in the limelight.

These are troubling times for the Indian judiciary. Earlier today, the Supreme Court collegium (the group of five senior-most judges) held a discussion in the national capital about the Centre’s decision to reject its recommendation seeking the elevation of Justice KM Joseph to the apex court. For the time being, the collegium has not taken a call on the matter.

Conventional practice dictates that if the collegium decides to recommend a Justice’s name for promotion, the government cannot stop the appointment, but only delay it.

The Centre’s decision to send back the recommendation has raised concerns about the message it may send. On the record, the Centre has raised a few technicalities behind its decision, but others see it a message that there will be consequences for judges if they rule against the government.

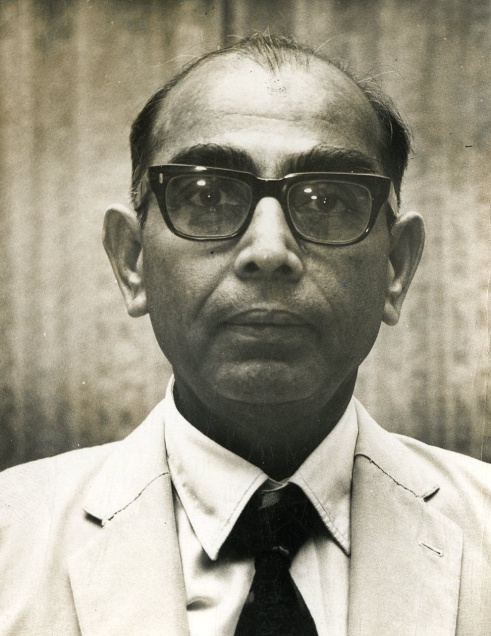

This isn’t the first time that the ruling executive and judiciary have come to loggerheads on the subject of appointments to the judiciary. In 1973, the Indira Gandhi government overlooked three judges with greater seniority (a significant determinant in the selection of judges) to appoint Justice AN Ray as the Chief Justice of India (CJI).

Many saw this move as an attack on the independence of the Judiciary.

Justice Ray would go onto controversially uphold the Indira Gandhi government’s decision to suspend all fundamental rights, including the right to life, during the Emergency. There was further outrage when the government overlooked Justice HR Khanna, the only dissenting judge in the Emergency case, for the post of Chief Justice of India in 1978.

Even Justice YV Chandrachud, the CJI from 1978 till 1985, had raised concerns about the Centre’s infringement in the appointment of judges.

“Mrs Gandhi never overruled me, but the government has got every weapon in its hands, so the vacancies are kept unfilled. The government tries artful persuasion, drops hints, and keeps egging you. No one is interested in having a good judiciary. No one is interested in having good judges,” he said.

What we see today is history repeating itself, albeit under different circumstances.

What is the Collegium system of appointing judges to the High Court and Supreme Court?

Evolved through a series of three judgements passed by the Supreme Court and not created by an Act of Parliament, the Supreme Court Collegium is led by the Chief Justice of India and four other senior-most judges of the court. The High Court collegium, meanwhile, is led by the Chief Justice of that particular court and four other senior-most judges of the court.

Also Read: How a Kerala Woman Made History By Becoming India’s 1st Female Supreme Court Judge

The candidates recommended by a High Court collegium require the assent of the Chief Justice of India and the Supreme Court collegium before the government is consulted on the matter. For the higher judiciary, the apex court collegium vets the list of potential candidates, and the government only comes in after the names selected for elevation are decided.

The Centre’s role, meanwhile, is restricted to conducting an Intelligence Bureau-led inquiry if a lawyer is slated for elevation to a judge in the High Court and Supreme Court. Regarding other appointments, the Centre can raise its objections and seek clarification from the collegium. However, if the collegium doubles down on its choice, the Centre must abide the decision before the President signs off on it.

This system of appointments emerged out of three rulings of the Supreme Court collectively passed known as the Three Judges Case, culminating in the historic Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association vs Union of India 1993 judgement.

In its landmark 1993 judgment, the apex court held that the independence of the judiciary, which is part of the basic structure of the Constitution, was being undermined by the primacy of the executive in key appointments.

Having said that, the system finds no mention in the Constitution. The procedure listed in the Constitution for judicial appointments comes under Articles 124(2) and 217.

“Every Judge of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President by warrant under his hand and seal after consultation with such of the Judges of the Supreme Court and of the High Courts in the States as the President may deem necessary for the purpose and shall hold office until he attains the age of sixty-five years. Provided that in the case of appointment of a Judge other than the Chief Justice, the Chief Justice of India shall always be consulted,” says Article 124(2).

“Every Judge of a High Court shall be appointed by the President by warrant under his hand and seal after consultation with the Chief Justice of India, the Governor of the State, and, in the case of appointment of a Judge other than the Chief Justice, the Chief Justice of High Court,” says Article 217.

Also Read: How the Supreme Court Came to the Rescue of India’s Drought Victims

Before the onset of a Collegium system, the popular belief brought on by the actions of the Indira Gandhi government was that “politically committed” judges or those beholden to the ruling establishment were appointed. The 1993 ruling was meant to change that dynamic. However, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley in a 2015 Facebook post spoke out against the court’s view.

“Both (Article 124 and 217) provide for the appointment to be made by the President in consultation with the Chief Justice of India. The mandate of the Constitution was that Chief Justice if India is only a ‘Consultee.’ The President is the Appointing Authority. The basic principle of interpretation is that a law may be interpreted to give it an expanded meaning, but they cannot be rewritten to mean the very opposite,” Finance Minister Arun Jaitley wrote, adding that the current system perpetrated the “tyranny of the unelected.”

What the judgment in 1993 did was to ‘reinterpret’ the word ‘consultation’ and wrest the power of appointments back from the executive.

Although the Collegium system brought greater independence in the functioning of the higher judiciary, critics argued that the process was non-transparent with allegations of nepotism rife.

“The system of checks and balances plays a vitally important role in ensuring that none of the three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial can limit the powers of the others. This way, no one branch can try and become too powerful. Except that this conceptual clarity has not translated into reality. Moreover, critics argue that recurring activism by the judiciary in matters under the direct jurisdiction of the executive has disturbed the delicate balance of powers enshrined in the Constitution,” says this editorial in the Millennium Post, a Delhi-based publication.

Also Read: Supreme Court Extends Aadhaar Deadline Until Bench Delivers Judgement

The Centre sought to address these issues by tabling the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Bill, which sought to give the government a greater say in the appointments of judges. The bill was passed by both Houses of Parliament, but the Supreme Court struck it down completely, although it did admit to the need for greater transparency in its functioning. Justice J Chelameswar, the only judge to dissent against his colleagues, made the same point.

He spoke out against the lack of transparency is both appointments and judicial proceedings.

“The need for transparency is more in the case of appointment process. Proceedings of the collegium were absolutely opaque and inaccessible both to public and history, barring occasional leaks,” he said. He also said that excluding the government completely from the process of appointments was “wholly illogical and inconsistent with the foundations of the theory of democracy and a doctrinal heresy.”

Instead, the court ordered the government to issue a new Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) for the appointment of High Court and Supreme Court judges in October 2015. This MoP sought to address the lack of transparency, especially in the higher judiciary without necessarily undermining the independence of the judiciary. After months of back and forth, the apex court finally sent its draft of the MoP to the Centre in March 2017.

However, the Centre earlier this year said that finalization of the MoP is going to take more time. With the MoP at an impasse, the collegium continues to function as before.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.