Sex Workers Defy Tradition: “Our Daughters Will Not Be Prostitutes, They Will Study.”

The Rajnat community relies on commercial sex work done by mothers, sisters and daughters to make ends meet. But these Rajnat women are determined their daughters will break free from this vicious cycle by gaining a proper education.

The Rajnat community relies on commercial sex work done by mothers, sisters and daughters to make ends meet. But these Rajnat women are determined their daughters will break free from this vicious cycle by gaining a proper education.

Is sex work, sometimes euphemistically referred to as “the world’s oldest profession”, really a profession? Over generations, the answer to this question hasn’t really changed. In popular public perception, sex workers continue to be seen as women who are either “immoral, criminal or carriers of sexually transmitted diseases,” or victims, who are trapped and exploited for their sexuality.

Although, these days, sex workers are rallying to alter this viewpoint – collectively they want to be seen as service providers with rights and entitlements – Rajnat women like Radha and Sheena, who were coerced into prostitution in the name of tradition and economic necessity, rue not having the option to pick their own future.

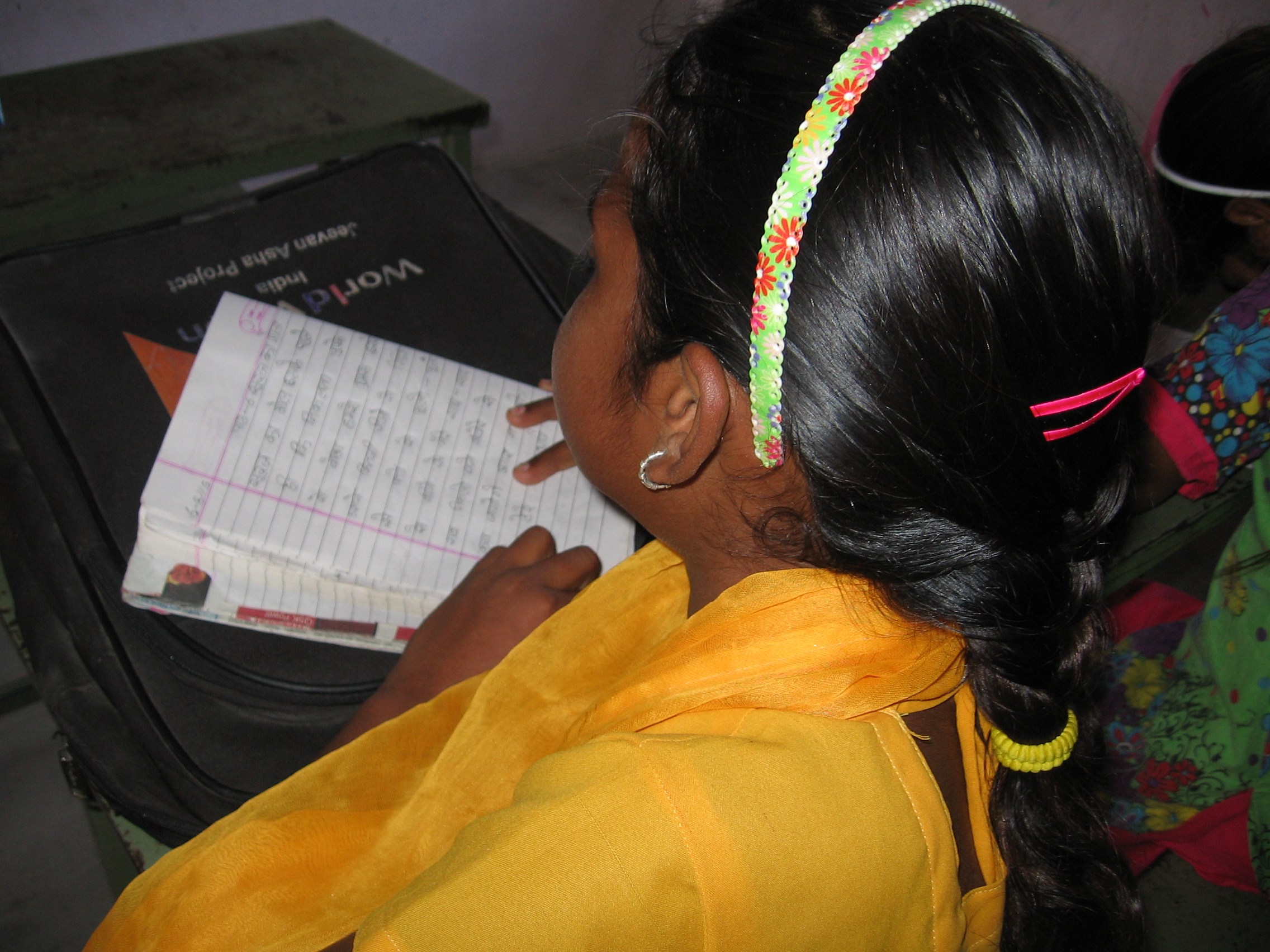

They are determined to ensure their daughters break free from this vicious cycle by gaining a proper education.

Pic credit: Abha Sharma

Radha, 45, is a former prostitute. She belongs to the Rajnat community that relies on commercial sex work done by mothers, sisters and daughters to make ends meet. Traditionally, they were ‘entertainers’ who enjoyed royal patronage. But ever since the dissolution of the princely states, post Independence, the women have had to take up prostitution full-time to keep the kitchen fires burning. It’s a given that a Rajnat daughter will take on her mother’s ‘profession’; conventional marriage and even an alternative line of work is simply out of the question.

But if Radha has her way then her daughter will never enter the trade. This mother of three from Bhojpura village on the outskirts of Rajasthan’s state capital Jaipur, says, “My daughter wants to be an air hostess and travel the world.” As she talks about her teenage daughter’s dream, her otherwise sombre face lights up. Radha fervently hopes that all her children will study well, become independent and overcome the ignominy of being Rajnats. However, in the very next moment, the worry returns as she verbalises the big fear that mars her life.

“What if my daughter doesn’t get a job? And she is unable to get married? Samay ka pata nahin, aage kya hoga (only time will tell what’s in store for her in the future),” she says with a sigh.

Indeed, that’s the worry that plagues every Rajnat mother, who wants her daughters to have the choice of building a different life from her own. Radha says, “I pray what happened to me shouldn’t happen to my daughter. But if circumstances so demand then who knows maybe she too might end up working at a dance bar in Mumbai.”

Sheena, too, fervently hopes that she will be able to give her two daughters the schooling they deserve.

“One of them wants to become a doctor and I do want to support her in every way I can. But I am not sure till when I’ll be able to pay for her higher education. We all want our children to study and have respectable occupations. But most of us don’t really have the means to give the kind of quality education that is needed for them to get well-paying jobs,” says the mother of three.

Radha astutely points out, “There is no denying that the government provides free schooling, midday meals, books, and so on, which is very important. Yet, one can’t overlook the fact that the quality of teaching is not up to the mark. If teachers are only going to be spending their time gossiping over cups of tea then what would our kids really learn? That’s one of the main reasons why we have to put aside more money and send them to decent private schools if we have to have any hope of them building lucrative careers. Right now, the biggest problem, as I see it, is that our community doesn’t have a say at the higher level. Everywhere there’s demand for ‘donation’ but we can’t afford it. Government assistance and scholarships for our community girls will facilitate in furthering their ambitions.”

Fortunately, these women do have some guidance and assistance coming their way from World Vision India, an international humanitarian organisation that works with disadvantaged communities across India. Since 2007, it has been working towards reducing the stigma attached with the Rajnats and encouraging the community to embrace change in villages like Bhojpura and Tilawala, located on the fringes of Jaipur.

Alok Peter, Gender and Development Coordinator, World Vision India, says, “Our experience shows that it takes time to break through regressive social customs and any change or enhancement in financial prospects requires a long-term, holistic intervention. So, while on the one hand we are speaking to women and community elders to bring about an attitudinal shift, on the other, we are focusing on organising vocational training with an emphasis on generating employment through small-scale industry and other suitable economic activities. So far, it’s been a daunting task because it’s far simpler for families to push their daughters into sex work rather than pursue other sources of livelihood that would require hard work and time.”

Any transformation is tough but that doesn’t mean it can’t happen. Shanta’s family in Tilawala village is an example for the entire community. Hers is an extensive, joint household of around 35 members, including half a dozen children of all age groups, who live together in a home built by them a few years back.

Shanta, a former sex worker, and her sister-in-law Geeta are among the first few women who linked up with World Vision India after it began creating awareness on health, education and employment issues in the area. “I really want my children to get a decent education and not make the same mistake their father made by leaving school mid-way,” she reveals.

Ideally, she would like them to follow in their uncle and aunt’s footsteps. Geeta’s brother-in-law is a practising doctor in Bagru, a town 30 kilometres from Jaipur, and his wife is educated as well.

Geeta herself never went to school and, therefore, vociferously advocates sending girls to school.

Pic credit: Abha Sharma

“Pahle humare paas koi zaria nahin tha. School bhi nahin the. Parivarwale ladkiyon ko padhane se darte the. Aarthik kaaran bhi the. Par ab sab freedom se bhejte hain (In my time, there was no way to ensure girls went to class simply because there were fewer schools, greater financial constraints and our families were afraid to send us by ourselves. But these days, we all send our girls to school without hesitation),” she says.

Considering the positive outlook of her family, it’s hardly surprising when Geeta discloses that her elder brother-in-law’s daughter is pursuing a career in nursing while her own son is studying medicine.

Of course, employability and marriage continue to remain the top two concerns for those eager to move away from the Rajnat way of life. For instance, Sanno’s niece is a graduate today but the family is having a tough time finding a suitable, educated groom.

“Our boys grow up in an unhealthy atmosphere and fall prey to bad habits like drinking and gambling. Moreover, many of them have barely studied and those that have are struggling to get well-paying jobs. Where would one find an eligible groom within the community? Men from other castes won’t marry our daughters. Nonetheless, I still think that’s no reason to go back to the way we were,” she says.

Barring a few exceptions, most Rajnat women openly talk of higher education and feel proud when family members make a name for themselves as teachers or medical practitioners, which is what most of them generally pursue. The desire to educate girls is especially strong as the spirited mothers truly believe that this can be the game-changer for them all.

(Names of the women have been changed to protect their identity.)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter (@thebetterindia).

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167