Why Freud Wrote Letters Praising This Bengali Pioneer of Mental Health Care in India

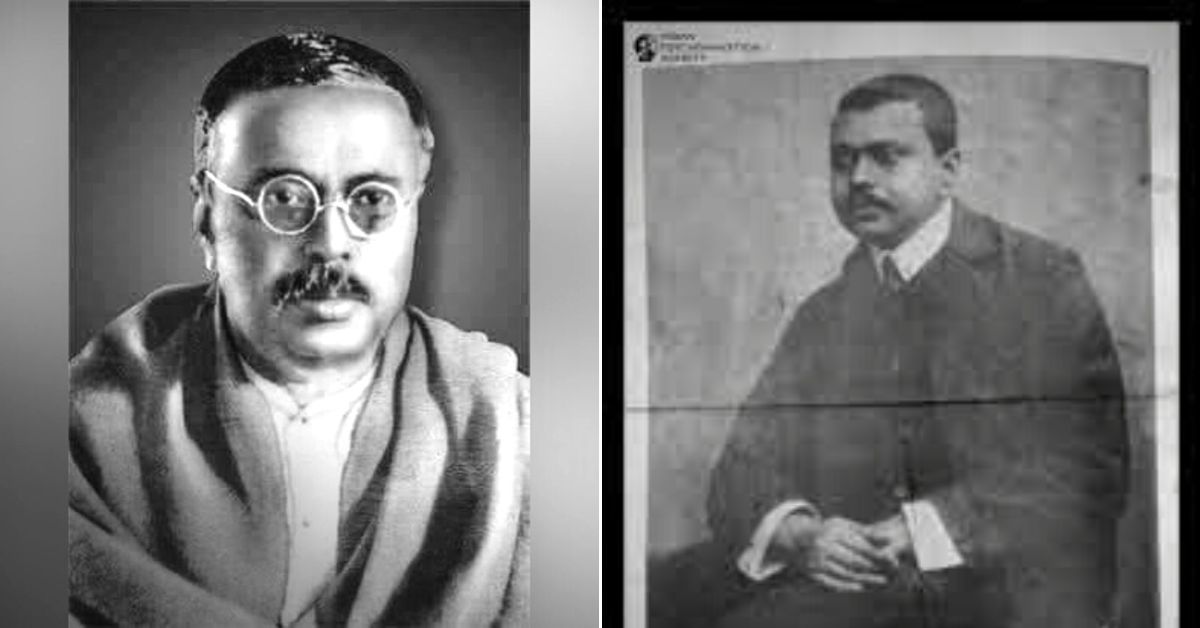

Playing a pivotal role in laying the foundation of mental health services in India, Dr. Girindrasekhar Bose was a pioneering psychoanalyst who set up India’s first psychiatric outpatient department (OPD) in Kolkata.

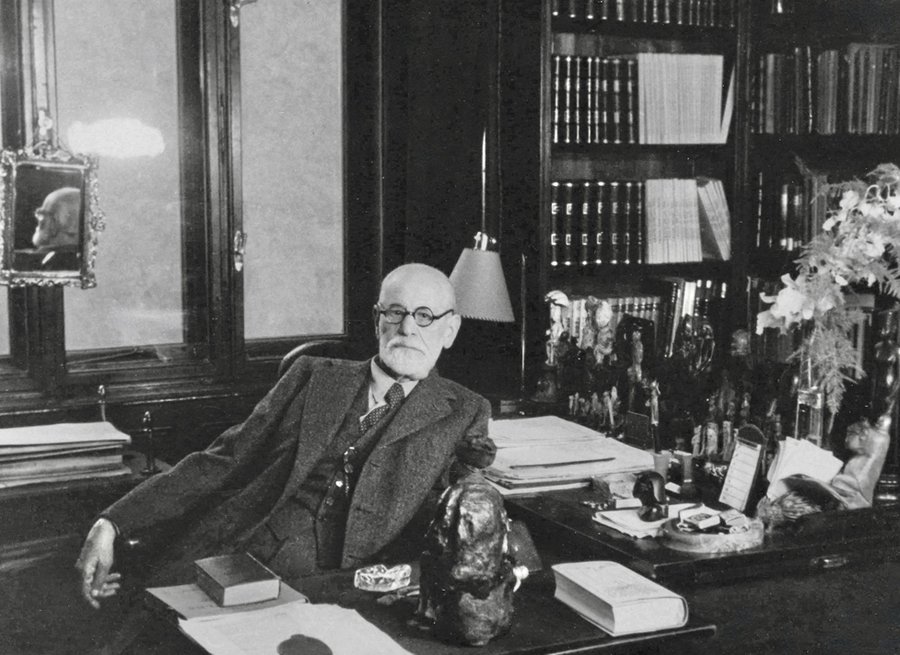

In March 1922, Dr Sigmund Freud, the legendary Austrian neurologist and founder of Western psychoanalysis wrote a letter to his colleague Lou Andreas-Salome, a Russian-born thinker and psychoanalyst, singing the praises of a fellow practitioner working in Calcutta (Kolkata).

“The most interesting item of news in the psycho-world is the foundation of the local group in Calcutta, led by Dr G Bose, a Professor Extraordinary,” wrote Dr Freud, in his letter to Andreas-Salome.

The ‘G Bose’ referenced in this letter was none other than Dr Girindrasekhar Bose (1887-1953). A Calcutta-based medical practitioner, he was specialising in psychotherapy at a time when the discipline was largely alien to the Indian populace and its medical fraternity.

Playing a pivotal role in laying the foundation of mental health services in India, Bose was a pioneering psychoanalyst who set up India’s first psychiatric outpatient department (OPD) in Kolkata on 1 May 1933. Called the General Hospital Psychiatric Unit, it was set up at the Carmichael Medical College (now known as Dr RG Kar Medical College, Kolkata).

Although they never met, Bose regularly corresponded with Freud, exchanging ideas, notes, photographs and even criticisms. On his own, he also contributed immensely to the larger academic discourse on psychology with his own theories.

By many accounts, Bose was an extraordinary personality. What Freud was referring to in the letter to his colleague was the process of establishing India’s first psychoanalytical society. Called the Indian Psychoanalytical Society, it was formally established on 26 June 1922.

Its head office is still standing at 14 Parsibagan Lane, the erstwhile residence of the Bose family, with its logo carrying a combined image of Shiva and Parvati, “symbolising the bisexuality of human beings (Ardhanarishvara: half male and half female),” notes SK Abdul Amin, a research scholar at Jadavpur University, writing for Live History India, in May 2022.

An ivory statue of Vishnu gifted to Freud by Girindrasekhar Bose on 75th birthday. Stayed on his desk till his death. pic.twitter.com/IC3HONXn2j— keerthik śaśidharan (@KS1729) August 1, 2014

Before becoming a pioneer

Born on 30 January 1887 in Darbhanga, Bihar, Bose grew up in prosperity with his father Chandrasekhar serving as the Dewan of the estate of local Maharaja Sir Rameshwar Singh. The youngest of nine children, Bose graduated from Presidency College in Calcutta before obtaining his M.D. from a medical college in the city. He was among the first to register for a new graduate training course in psychology announced by Calcutta University in 1916.

Upon completion, he became a lecturer at the varsity’s Department of Psychology and ended up becoming the head of the department from 1928 to 1938.

According to Amin, “Bose was the first to earn a doctorate in psychology from an Indian university”, after finishing his thesis titled ‘The Concept of Repression’ in 1921. In the same year, he began corresponding with Freud. Even though the two shared an age difference of 30 years, they corresponded for nearly two decades.

Bose and Freud

In his very first letter, Bose articulated his unique ‘opposite wishes’ theory.

As scholar I.F. Grant noted in his 1933 paper published in the Indian Journal of Psychology, “According to this theory every wish in the human being arises in twofold form, the one member of the pair being the exact opposite of the other member. The one wish is conscious, its opposite number is unconscious. Normally the conscious side is satisfied by appropriate action and the unconscious by identification. When one member of an opposite pair of wishes is satisfied, a tension is produced until the opposite wish is also satisfied.”

Grant illustrates this theory with a simple example.

“For example, if A strikes B, B’s wish to be struck is satisfied and the active wish to strike becomes conscious and B now wishes to strike A. Before A struck B, the two opposite wishes in B were latent and each was inhibited by the other. This is the basis of retaliation and punishment, both in the individual and in society. It is one of the mechanisms via which the superego [“ethical component of the personality” which “provides the moral standards by which the ego operates”] is formed,” he adds.

Bose’s theory of ‘opposite wishes’ in many ways laid the ground for groundbreaking Western psychology concepts developed in the future like ‘projective identification’ (“the psychological process by which a person projects a thought or belief that they have onto a second person”) and ‘intersubjectivity’ (“a shared perception of reality between two or more individuals”).

Responding to Bose’s letter about his thesis, Freud expressed admiration by saying he was “glad to testify the correctness of its principal views and the good sense appearing in it.” He went on to add, “It is interesting that theoretical reasoning and deduction does play so great a part in your demonstration of the matter which with us is rather treated empirically”.

In the following year, the Indian Psychoanalytical Society was established and received affiliation from the International Psychoanalytical Association.

Soon, Freud also requested Bose to join the editorial board for both the International Journal of Psychoanalysis and German Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse as “leader and representative of the Indian group”. However, their relationship wasn’t merely one of friendship and a meeting of minds. Bose challenged Freud, disagreeing with his version of the famous Oedipus complex.

“I do not agree with Freud when he says that the oedipus wishes ultimately succumb to the authority of the super-ego. Quite the reverse is the case. The super-ego must be conquered and the ability to castrate the father and make him into a woman is an essential requisite for the adjustment of the oedipus wish. The oedipus isresolved not by the threat of castration, but by the ability to castrate,” noted Bose.

Treating mental health

Besides his academic work, however, “Bose [also] greatly helped the surgeons by putting the patient in hypnotic trance (mesmerism) and mastered the technique of hypnotism and treated mental patients,” notes a profile published by the Indian National Science Academy.

Despite his regular correspondence with Freud and the Western academia, Bose never shied away from critiquing them and offering his own interpretations of psychoanalysis.

Even Freud acknowledges the unique perspective that Bose offered.

“The contradictions within our current psychoanalytic theory are many..and I reproach myself for not having given attention to your ideas before..I suspect that your theory of opposite wishes is practically unknown among us and has never been mentioned or discussed. This attitude was to be abolished. I am eager to see it weighed and considered by English and German analysts all over.”

His understanding of psychoanalysis was further informed by Indian philosophy. From studying Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra to translating and interpreting traditional Sanskrit texts and writing a groundbreaking article on the Bhagavad Gita, he found inspiration in the traditional. His 1931 article on the Gita published in Probashi, a Bengali journal, is still considered a groundbreaking attempt at establishing a correlation between Hindu philosophy and Western psychology.

But his desire to reach a local audience extends far beyond. In 1928, he published Swapna, which presented Freud’s concept of dreams to Bengali readers. Years later in 1953, he published Manobidyar Paribhasha, an explainer of psychological concepts to Bengali readers.

More importantly, however, Bose arrived at psychoanalysis at a critical time in Indian social history.

According to scholar Ashis Nandy, “Bose turned to psychoanalysis at a time when the traditional social relationships that took care of most of the everyday problems of living — the neuroses and less acute forms of psychosis — were breaking down in urban India.”

“The first victims of this change were the psychologically afflicted; they were no longer seen as aberrant individuals deserving a place within the family and the community, but as diseased and potentially dangerous waste products of the society. In 1933, he established India’s first psychiatric out-patient clinic in Calcutta’s Carmichael Medical College and Hospital,” he added.

A few years later in February 1940, the Indian Psychoanalytic Society established a hospital and research centre at Calcutta’s Lumbini Park.

“Bose took another radical step and set up a private nursing home and clinic on 5 February 1940, at Bediadanga Road, in Tiljala, near Ballygunge [Kolkata]. The land was gifted by his brother Rajsekhar and the nursing home was managed by the Indian Psychoanalytical Society before it attained mental hospital status under the Lunacy Act in 1952. It was renamed Lumbini Mental Hospital,” according to Abdul Amin.

In 1942, the legendary Bengali rebel poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, sought treatment at the nursing home under Bose’s supervision following a serious illness resulting in a loss of speech. Decades later, however, the State government took over the hospital.

At the end of the decade, he even set up a school for children with special needs “organised on psychoanalytic principles”. In 1951, this institution became a residential home called Bodhi Peet.

Till his eventual demise in 1953 at the age of 66, Bose played a pivotal role in laying the foundation of mental health support and treatment in India today. His passing, however, did not curtail his legacy.

On the request of Anna Freud, the youngest child of Sigmund Freud, Bose’s wife Indrumati donated the Bose-Freud letters to the Freud archives in London a decade after his death. In 1970, the Girindra Sekhar Clinic was established to offer psychiatric and psychoanalytical services to those suffering from mental illness at affordable rates.

His legacy lives on till this day.

(Edited by Pranita Bhat; Images courtesy Facebook/Indian Psychoanalytical Society)

Sources:

‘Girindrasekhar Bose: The Father of Psychoanalysis in India’ by SK Abdul Amin; Published on 16 May 2022 courtesy Live History India

‘The Beginnings of Psychoanalysis in India: Bose-Freud Correspondence’; Published by Indian Psychoanalytical Society in 1964

Profile of ‘Professor GS Bose’ by Indian National Science Academy

General: G. Bose. ‘A New Theory of Mental Life.’ Indian Journal of Psychology, 1933, Vol. VIII, pp. 37–157

‘Opposite Wishes’ by Alf Hiltebeitel; Published in September 2018 courtesy Oxford University Press

‘Bonfire of Creeds: The Essential Ashis Nandy’ (339-393 p.); Published by Oxford University Press in 2004

‘Girindrasekhar Bose—India’s first psychoanalyst was pen pals with Sigmund Freud’ by Krishnokoli Hazra; Published on 20 April 2023 courtesy The Print

Psychology Concepts

Psychoanalysis Between Vienna and Calcutta by Candela Potente

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.