Satirizing Teachers to Nehru: The Cartoonist Who Took On World’s Most Influential Leaders

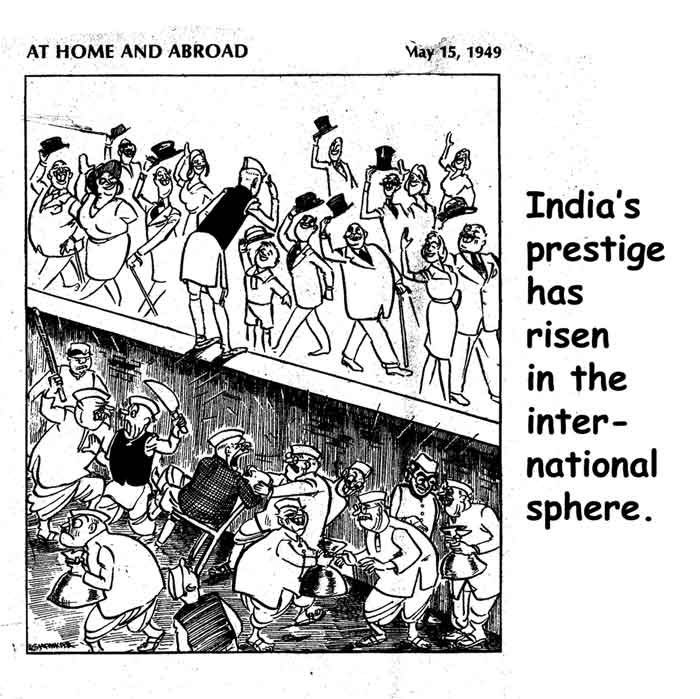

From Independence through Emergency and beyond, cartoonist and political satirist Shankar wasn't afraid to make fun of influential leaders.

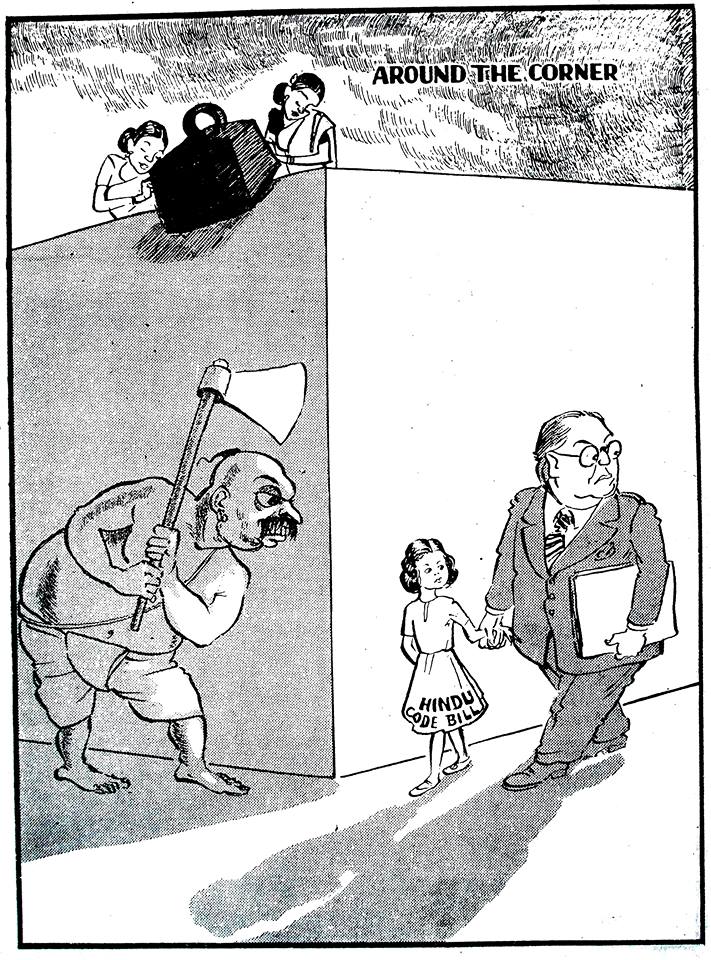

It’s nearly impossible for political cartoonists in India to escape the wrath of the establishment. If they poke fun or mock influential political leaders, they are either taken to court on a variety of charges, driven out of their workplace or face intense abuse online.

In certain cases, even sharing a cartoon can land you in prison. Take the example of Ambikesh Mahapatra, a professor of chemistry at the prestigious Jadavpur University in West Bengal, who was arrested in April 2012 after he forwarded an email to his friends that contained a cartoon about a chief minister. It took him 11 years to get cleared of all charges.

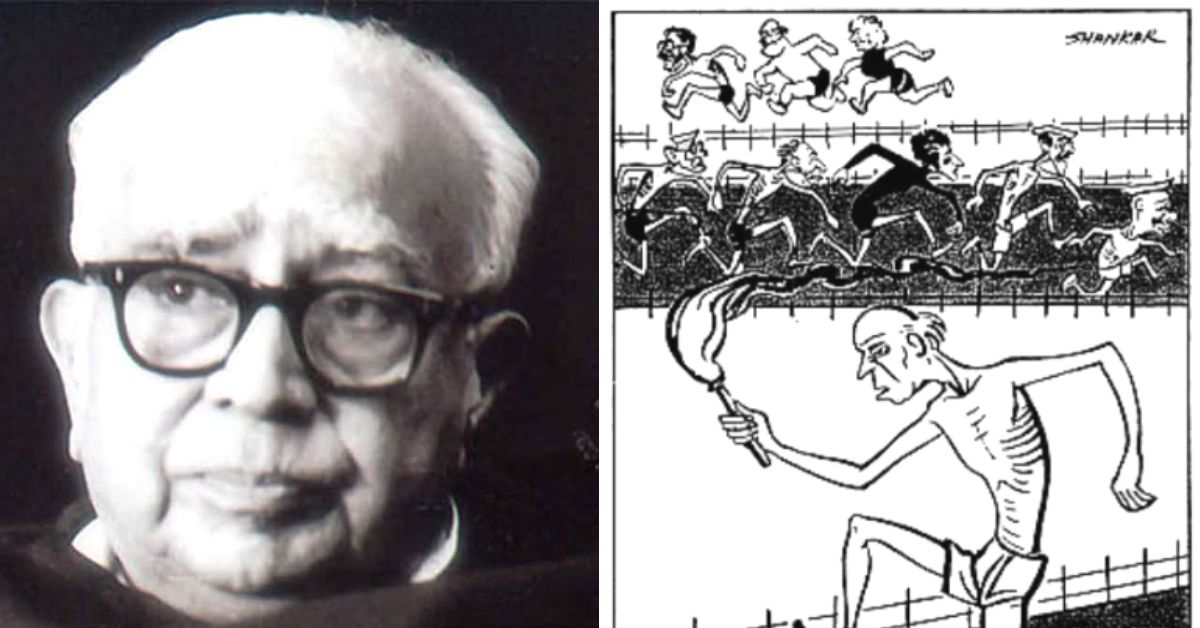

It’s not hard to guess how Keshav Shankar Pillai, the godfather of political cartooning in India, would have reacted to such events. Popularly known as just ‘Shankar’, the legendary cartoonist and illustrator was among the pioneers of political satire in post-Independence India living through some of the most prominent events ranging from Independence to the Emergency.

Here’s his remarkable story.

Anti-establishment from the start

Born in Kayamkulam, Kerala, on 31 July 1902, Shankar began his journey as a cartoonist caricaturing people in school. One of his first targets was a teacher sleeping in the classroom. Although the cartoon of a school teacher dozing off got him in trouble with his headmaster, an uncle recognised his talent and encouraged him to draw more. After school, he studied painting at the Ravi Varma School of Painting at Mavelikara (Raja Ravi Varma College of Fine Arts).

While cartooning started off as a hobby for Shankar, it was Pothan Joseph, then editor-in-chief of the Hindustan Times who hired him as a staff cartoonist in 1932. His drawings, according to some of his own proteges, weren’t very good at the start.

In a bid to perfect his craft, he undertook a rigorous training at the Slade School of Art in the United Kingdom and other institutions in Europe for over a year to improve his drawings. After finishing his course, he came back to work for the Hindustan Times until he quit in 1946.

Most of his cartoons were targeted at the British colonial administration. His cartoons depicting Viceroys like Lord Willingdon and Lord Linlithgow and leaders of the independence movement like Mahatma Gandhi and Mohammad Ali Jinnah often got him in trouble.

According to a story in The Hindu Business Line, “One of his most famous cartoons that appeared in the Hindustan Times in the early 1940s showed the British Viceroy Lord Linlithgow as Goddess Bhadrakali, standing over a burning body in a cremation ground.”

Interestingly, though, Linlithgow and his wife expressed appreciation for his cartoon. But it was Gandhi who sent a rather scathing postcard to Shankar which among other things criticised his cartoons of Jinnah and even included advice on the ethics of cartooning.

“Your cartoons are good as works of art. But if they do not speak accurately and cannot joke without offending, you will not rise high in your profession. Your study of events should show that you have an accurate knowledge of them. Above all you should never be vulgar. Your ridicule should never bite,” read the postcard that Gandhi sent in 1939.

Ritu Khanduri in her book Caricaturing Culture in India notes, “Shankar’s cartoons in Hindustan Times were both part of and marked the ethos of an emerging nation.” But his fearlessness and utter disregard for authority would result in him leaving the publication.

As Khanduri notes in her book, “With the increasing temp of nationalist politics in India, newspaper cartoons invited interpretation not just about the British mind, but also about competing Indian political minds. They also generated sentiments of pleasure and hurt that place representation in the tricky terrain of emotion.”

“To pinpoint the emotion of the cartoons involved meaning-making that insisted upon articulating subjective experience as a social reality of colonial politics, and pinpointed the position of women and Muslims in the liberal agenda of a ‘gestating nation state’,” she adds.

In 1946, Shankar began butting heads with the editor of the paper, Devdas Gandhi (Mahatma Gandhi’s son) over his unwillingness to tone down cartoons critical of prominent Congress leader C Rajagopalachari. After all, Devadas was Rajagopalachari’s son-in-law too.

“The various circumstances surrounding Shankar’s resignation from the Hindustan Times suggest that by 1947, the press in India began to experience the strains of political affiliations made more complex by the interweaving of kinship among the industry, press barons, and politicians. In India, industrialists owned and financed the press, an unsurprising fact, since industrialists financed the Indian nationalist movement,” wrote Khanduri.

He would eventually resign in 1946, even though Mahatma Gandhi famously asked him at the time, “Did Hindustan Times make you famous, or did you make Hindustan Times famous?”

Challenging Nehru

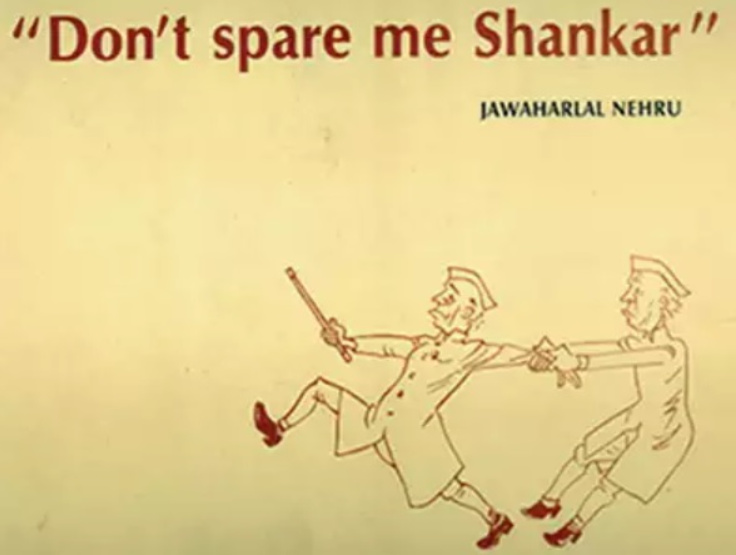

Following his stint with the Hindustan Times, Shankar set up his own satirical magazine called Shankar’s Weekly. The weekly would give future cartoonists like RK Laxman, Bireshwar, Kutty, Narendra, Unny and Kevy, among others, their start. It was Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who would launch the magazine even though Shankar described his weekly as “fundamentally anti-establishment, while never toeing any particular line in politics or in anything else.”

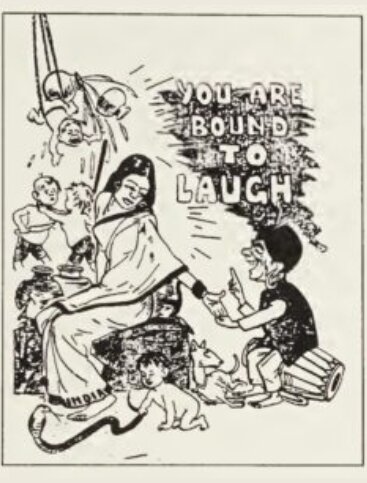

“In the first issue of Shankar’s Weekly, the only humour magazine ever to enjoy any success in India, there was a drawing of India personified as a distraught woman surrounded by screaming, bickering children. At her side, a puckish Shankar was trying to give laughter’s sweet solace,” wrote Lee Siegal in his 1987 book Laughing Matters: Comic Tradition in India.

The relationship between Shankar and India’s first prime minister was rather unique. According to some estimates, Shankar had featured Nehru in more than 4,000 cartoons. In fact, even before they had met in person, Nehru would every now and then send clippings of Shankar’s cartoons to his daughter Indira alongside letters he wrote to her from prison.

There were two cartoons of Nehru that particularly stood out.

One poked fun at Nehru’s claims that India was ready to face the Chinese challenge, while also warning against any hasty action. “The cartoon depicted a worried and chastened Nehru pulling back an agitated and war-ready Nehru,” notes a blog post by G Sreekumar.

The second cartoon was published about 10 days before Nehru passed away in 1964. Back then, there were many rumours about who would succeed Nehru.

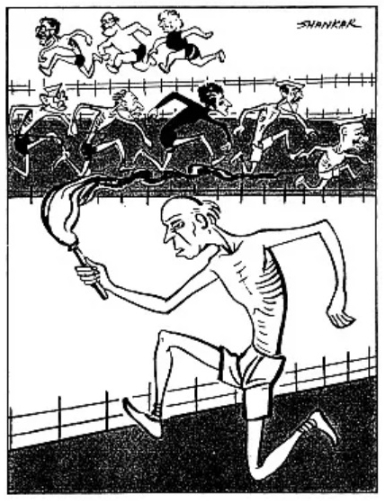

According to this 2009 tribute in The Hindu, the cartoon depicted “An emaciated and exhausted Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, with a torch in hand, runs the final leg of a race, with party leaders Gulzari Lal Nanda, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Morarji Desai, Krishna Menon and Indira Gandhi in tow.”

In response, Nehru reportedly remarked, “Don’t spare me, Shankar”.

In fact, this is how Nehru described Shankar and his cartooning craft — “Shankar has that rare gift, rarer in India than elsewhere, and without the least bit of malice or ill-will, he points out, with an artist’s skill, the weaknesses and foibles of those who display themselves on the public stage. It is good to have the veil of our conceit torn occasionally.”

Meanwhile, Shankar described Nehru as a “great man, a truly great man”. He also noted how Nehru often thanked him “for helping him spot his inherent weaknesses.”

“He liked to be reminded that he too was mortal. Perfection is not for any man, however powerful and highly placed he may be. Nehru had the wisdom to realise that,” said Shankar.

Emergency

Unfortunately, two months into the Emergency imposed by Nehru’s daughter and prime minister, Indira Gandhi, in 1975, the satirical magazine shut shop. While many believed that the magazine closed down because of the Emergency, Shankar denied those claims.

The reason for shutting down was more basic. “We could have taken the Emergency in our stride, but the burden of running a weekly magazine on a shoe-string was too much,” he said.

In the final edition Shankar’s Weekly, he wrote: “…our function was to make our readers laugh — at the world, at pompous leaders, at humbug, at foibles, at ourselves. But, what are the people who have a developed sense of humour? It is a people with certain civilised norms of behaviour, where there is tolerance and a dash of compassion.”

Literature for Children

Once the magazine shut down, Shankar turned his attention to writing and illustrating children’s books and dolls. In 1957, he founded the Children’s Book Trust on Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg in Delhi, which still stands today.

Speaking to The Hindu Business Line in July 2019, Navin Menon, an editor at CBT under Shankar, recalled how “Shankar himself penned the first stories. Then he felt it didn’t quite reflect well on the organisation to have just one writer. So he started publishing his stories in the name of his family members. By and by, he looked for stories by outsiders.”

CBT would go on to become a pioneer of children’s books in India, publishing popular titles like Stories from Panchatantra, Life with Grandfather and Mother is Mother, among others.

In the same article, a former director of the National Book Trust, said, “Post-Independence children’s literature in India was rich in text, but not much attention was paid to illustrations and design. The market was flooded by highly subsidised, child-friendly colourful Soviet books. By establishing CBT, Shankar offered an attractive option to parents wanting well-illustrated books with Indian creative works, and stories from our history and mythology.”

Meanwhile, following a gift he received of a Hungarian doll, Shankar went on a spree of collecting dolls from around the world and organising doll-making workshops across India.

As a cartoonist, something about the Hungarian doll figure must have inspired him. It’s a hobby he developed in the 1950s, resulting in the creation of the International Doll Museum in 1965, which is today housed in the same building as the Children’s Book Trust. If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change. Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution- By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike. Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

Shankar eventually passed away on 26 December 1989 at the age of 87, but not before leaving behind an incredible legacy.

(Edited by Divya Sethu. Images courtesy Children’s Book Trust, Twitter)

Sources:

‘Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History in the Modern World’ by Ritu Gairola Khanduri; Click here and here to read it

‘Sundays with Shankar’ by G Sreekumar; Published on 10 March 2022 courtesy his website

‘K Shankar Pillai, the cartoonist who taught a nation to laugh at itself’ by Meghaa Aggarwal; Published on 26 July 2019 courtesy The Hindu Business Line

‘Don’t spare me, Shankar’ by Deepa Karup; Published on 5 August 2009 courtesy The Hindu

‘Fifty and counting’ by Sangeeta Barooah; Published on 15 October 2007 courtesy The Hindu

‘Shankar, the political cartoonist to whom Nehru said ‘Don’t spare me!’ by Rachel John; Published on 22 December 2022 courtesy The Print

Children’s Book Trust

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167