Why Children From Tokyo to Berlin Once Wrote Letters to Nehru Asking for Elephants

Children from Tokyo, Berlin, Amsterdam and even a small town in Canada wrote letters to former prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, requesting him to send them an elephant from India. Here's a unique story of how he turned these requests into small diplomatic victories.

In 1943, as World War II raged on, the mayor of Tokyo issued an order to kill the three elephants lodged in Ueno Zoo, Japan’s oldest zoo, located in the northern part of the city. There were fears of what would happen to the local populace if these elephants broke free during air raids.

Of the three elephants, two were brought from India — Jon (male) and Tonkī (female) — back in 1924, while the third — Hanako — came from Thailand. Over the years, they became very popular attractions at the Ueno Zoo, especially with young children. But out of fear for their escape during bombing raids, the mayor of Tokyo showed no mercy and issued an order to kill them.

First, authorities sought to euthanise them with needles, but their hides were too thick. They even attempted to poison their food, but the elephants were smart enough to not eat the meals served their way. Eventually, it was decided that the three elephants would be starved to death.

Suffice it to say, it was a disturbing set of events. “There are accounts of how Tonki, who lasted the longest of the three, desperately performed tricks every time a human passed his enclosure, in the vain hope of some food,” wrote Pallavi Aiyar in her book ‘Orienting: An Indian In Japan’.

While the adults had no time to grieve their loss amidst other tragedies, the children never forgot. A few years after the war, as Japan began picking up the pieces, two plucky seventh-graders submitted a petition to the upper house of the Japanese Parliament expressing their unhappiness at not being able to see an elephant at the zoo and requesting whether a new one could be procured. This petition would eventually snowball into a public campaign.

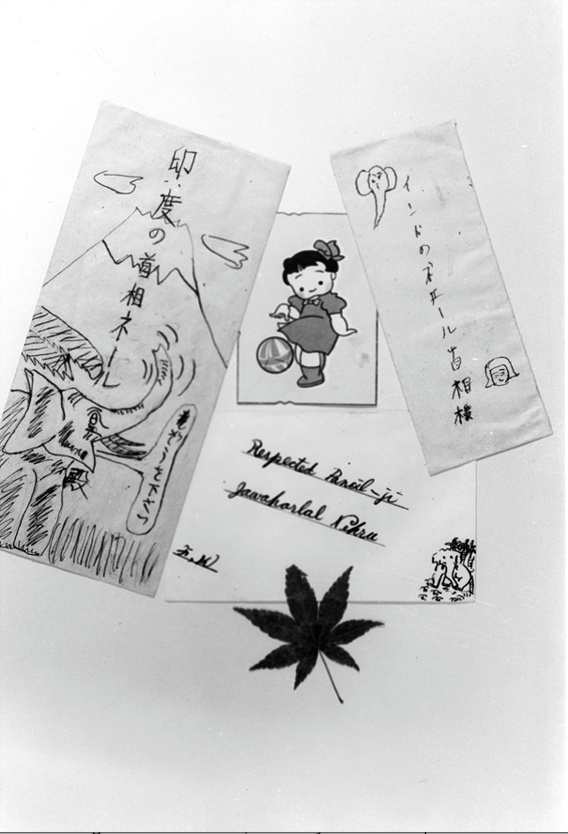

As Pallavi notes, “In the end, the Tokyo government collected over a thousand letters from children, all addressed to the prime minister of India, pleading with him to send them a replacement elephant.” A 4 July 1949 report in Time Magazine confirms the same news.

Here’s where the story gets interesting. According to Time Magazine, “Recently, Tokyo moppets made friends with personable young Himansu Neogy, a Calcutta exporter who had taken time off during a business trip to visit the city’s schools. They gave him bouquets of flowers and posed with him for group pictures. When Neogy was about to go back to India, they begged him to intercede on their behalf with the then prime minister Nehru to send them an Indian elephant.”

About a week before the Time Magazine report was published, Neogy dropped in at Jawaharlal Nehru’s office and left a pouch of 815 letters from children in Japan.

One such letter in English written by Sumiko Kanatsu, a girl pupil in Negishi primary school, stated: “At Tokyo Zoo we can only see pigs and birds which give us no interest. It is a long cherished dream for Japanese children to see a large, charming elephant … Can you imagine how much we want to see the animal?” Meanwhile, another letter written by Masanori Yamato of Seisi Grade School noted, “The elephant still lives with us in our dreams.”

Upon receiving these letters, Nehru directed the Ministry of External Affairs to coordinate with the princely states to procure an elephant and organise funds and transportation. Procured from the erstwhile princely state of Mysore, Nehru named the elephant, Indira, after his daughter. Barely months after Nehru received those letters, Indira (the elephant) made her way to Tokyo.

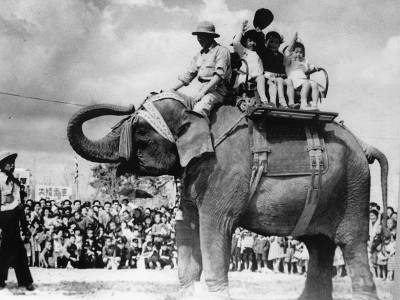

As Aiyar wrote, “Nehru acquiesced, and Indira’s arrival at Ueno on 25 September 1949 caused much excitement in Tokyo. The zoo was packed to capacity with thousands of people trying to glimpse the new elephant. Tadamichi Koga, who was the head of the zoo at the time, later said that receiving Indira was one of the happiest moments in his life.”

Nehru also took the time to address the children of Japan when he sent them an elephant.

In a letter, he wrote, “I hope that when the children of India and the children of Japan will grow up, they will serve not only their great countries but also the cause of peace and cooperation all over Asia and the world. So you must look upon this elephant, Indira by name, as a messenger of affection and goodwill from the children of India. The elephant is a noble animal. It is wise and patient, strong and yet, gentle. I hope all of us will also develop these qualities.”

Since Indira could only follow commands in Kannada at the time, Aiyar wrote how her two Japanese handlers learnt the language from “the two Indian mahouts who had accompanied the elephant from Mysore”. It took both Japanese handlers two months to learn enough Kannada that allowed them to establish some rapport with her. About eight years later in 1957, Prime Minister Nehru and his daughter Indira met her namesake in person when they visited Japan.

Till her death, the elephant Indira served as an emblem of the friendship between Japan and India.

Not the last elephant

But this wouldn’t be the last time that Nehru would receive such unusual requests. During World War II, zoo animals in Berlin also faced similar treatment as they did in Tokyo. A couple of years after the war, it was the children of Berlin who lamented the sight of no elephants in the Berlin Zoo. They too wrote letters to Nehru requesting him to send an elephant.

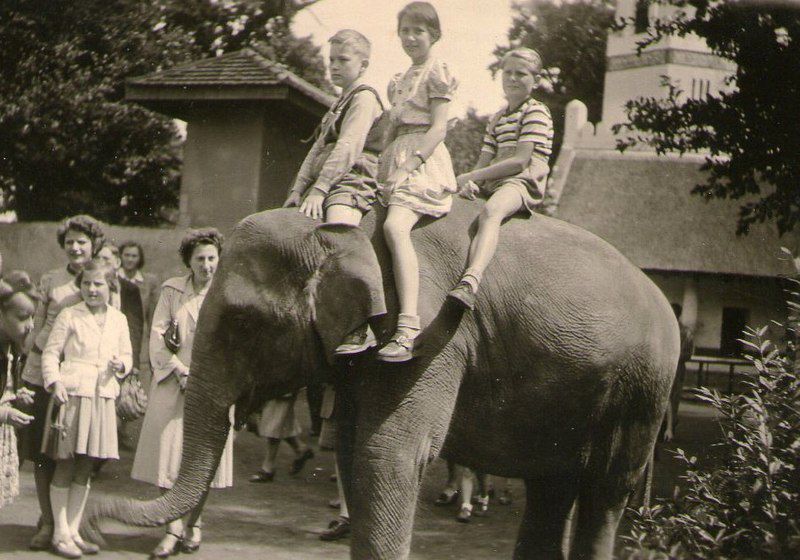

He received those letters and pledged to deliver one for the children of Berlin. In June 1951, a three-year-old female elephant named Shanti, which means ‘peace’, made her way to Berlin.

Fast forward more than two years later in the winter of 1953, Nehru received another letter from a five-year-old boy in Canada named Peter Marmorek. “Dear Mr Nehru,” it began. “Here in Granby, a small town in Canada, we have a lovely zoo, but we have no elephant[s].”

A young Marmorek had heard from his father that Nehru was in possession of “lots of elephants and could probably dig up one for us.” Taking his father’s words seriously, the five-year-old added, “I never knew that elephants lived underground, [but] I hope you can send us one.”

In early December 1953, Marmorek received a response to his letter from none other than India’s prime minister. While Nehru didn’t promise an elephant outright, he assured the five-year-old that he would not forget his polite request. Also, in a moment of humour, Nehru addressed the boy’s confusion, when he wrote, “Elephants do not live underground. They are very big animals and they wander about in the forests … It is not easy to catch them.”

The Canadian Press got news of this letter and it was reported widely. Even the Canadian prime minister was notified of the letter. Naturally, the five-year-old boy became a local celebrity. Over the Christmas holidays, meanwhile, a petition based on his letter to Nehru was circulated by his hometown of Granby, garnering the signatures of over 8,000 children.

Writing for The Caravan, Nikhil Menon, a historian, noted, “The children of Granby eventually had their wish granted. In 1955, a two-year-old elephant calf named Ambika was transported from the forests of Madras state to Montreal, before being moved to the Granby zoo. Peter Marmorek was there to welcome her and even gave a speech to celebrate her arrival.”

“Despite Ambika’s friendliness, he [Peter Marmorek] was nervous about her size. His parents reassured him that Ambika was vegetarian and therefore not a threat. The boy responded, ‘But how does the elephant know that I’m not a vegetable?’,” he wrote.

In the following year, a very similar scenario played out in the Netherlands. It resulted in the arrival of a calf named Murugan from the Malabar forests to Amsterdam in November 1954. Murugan would thrive in the Amsterdam zoo and die in June 2003 at the ripe old age of 50.

But why did the Indian government send elephants as gifts to children overseas? Although Nehru loved children, there was a bigger reason at play. Menon makes a mention of what the Indian High Commission in Canada wrote to the Ministry of External Affairs.

“No doubt it will be an appealing gesture of friendliness and goodwill,” the letter stated.

Menon also makes a mention of what Kameshwari Kuppuswamy, a social worker nominated by the Planning Commission to study rural community development programmes in North America in the 1950s, wrote in a letter she addressed to the mayor of Granby.

“India has been receiving several gifts from your country, particularly foodstuffs like wheat and milk powder. The only way by which we can show our appreciation and return the kindness is by way of sending something which your country does not possess,” wrote Kuppuswamy.

Menon, however, presents an interesting explanation.

“Besides gratifying children, the gesture of gifting elephants, such as Ambika and Murugan, symbolised how postcolonial India wished to be viewed on the international stage: generous and friendly, with a keen sense of fostering ties with the peoples of the world. During a period in which it relied so heavily on external aid, these gifts provided India laudatory news coverage and helped shape a flattering image, as an indulgent young nation that showered presents on children the world over,” he wrote.

Eventually, such gifts would be made illegal following a 2005 ban issued by the environment ministry on transferring animals across international borders.

Coming back to Marmorek, however, he would regularly visit Ambika at the Granby zoo, but soon lost contact with her once he moved out of town.

But in a blog published in the same year (2005), he wrote, “Ambika from whom I had learned that India was a magical country; if you wrote to it, they would send you an elephant.”

(Edited by Pranita Bhat)

Sources (text and images):

‘Orienting: An Indian in Japan’ by Pallavi Aiyar; Published on 3 August 2021 courtesy HarperCollins India

‘Jumbo Exports: India’s history of elephant diplomacy’ by Nikhil Menon; Published on 1 March 2019 courtesy The Caravan

Koehl, Dan. Indira, Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) located at Ueno Zoo in Japan. Elephant Encyclopedia

‘JAPAN: The Charming Elephant’; Published on 4 July 1949 courtesy Time Magazine

‘Photo 9794’ courtesy the archives of External Affairs Ministry

‘The Tragic Ordeal of the Berlin Zoo in World War II’ by Khalid Elhassan; Published on 10 May 2019 courtesy History Collection

The Paperclip/Twitter

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.