Camera Over Gun: Forgotten IFS Officer Behind India’s Only Wolf Sanctuary

SP Shahi’s contributions to the protection of wolves, and his role in bringing them back from the brink of extinction, are largely forgotten today. The forest officer was behind India’s only wolf sanctuary, Mahuadanr, in Jharkhand.

There are about 3,100 grey wolves (Canis lupus) left in India. Like many endangered species in the world today, loss of habitat poses the primary threat to their existence.

“The wolf, unlike the tiger, is not a creature of forests. It requires vast areas, and manages to live in the interstices of agricultural spaces that are left fallow by farmers dependent on rainfall as their only source of irrigation,” noted Abi T Vanak, senior fellow at ATREE in Bengaluru, and Mihir Godbole, president of The Grasslands Trust, Pune, in a May 2022 column for The Hindu.

Tragically, according to the Government of India’s Wasteland Atlas of India report, a significant portion of the wolf’s native habitat lie in barren wastelands, where the government has prioritised solar and other renewable energy projects, tree-planting drives for carbon sequestration and other such “development” activities.

“The semi-arid savanna grasslands and rocky areas of the Deccan plateau, in Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh — along with some areas of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan — are among the last strongholds of the Indian wolf,” Vanak and Godbole note.

Their survival, they argue, depends a great deal on their relationship with nomadic pastoralist communities whose goats and sheep graze on these grasslands. It’s a relationship that swings from acceptance-reverence to outright revenge, given how these wolves prey on sheeps and goats for survival.

“Only by granting the savanna grasslands of India their legitimacy as a natural habitat, and recognising the deep and intricate dependencies between the human and non-human denizens of these vast open landscapes, do we have a chance of saving the wolves,” they argue.

Given this context, it’s important to remember Mahuadanr Wolf Sanctuary in Jharkhand — the only sanctuary in India dedicated to wolf preservation.

The forest officer who first saved wolves from extinction

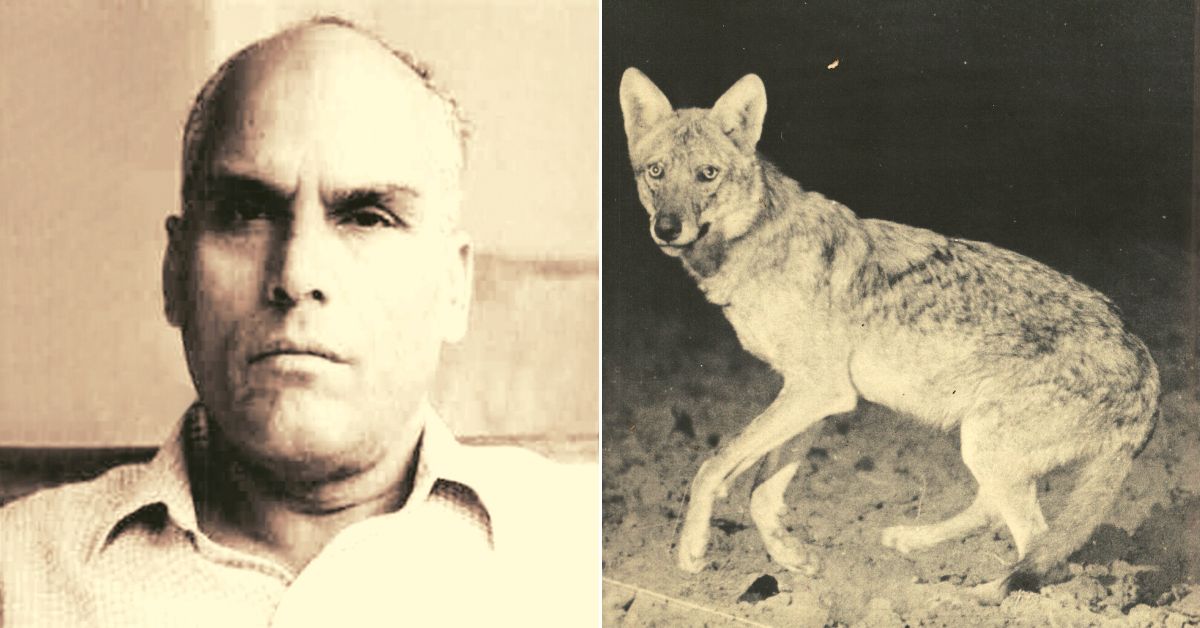

The wolf sanctuary only exists because of the efforts of a forgotten Indian Forest Service officer, SP Shahi, who paid close attention to how wolves were hurtling towards extinction back in the 1960s.

“Back then, the preferred habitats of wolves — scrub and open forests and grasslands — were the easiest to bring under the plough, and swiftly converted into agricultural land. Thus their habitat was rapidly declining. Simultaneously, a policy of elimination of wolves was followed on a wide scale by the British authorities and the killing continued into independent India,” says wildlife historian Raza Kazmi, in a conversation with The Better India.

In a recent Twitter thread, he noted, “Shahi, unlike most forest officers of his era — to whom the mosaic of ravines, open thin Sal forest and rainfed fields of the Mahuadanr valley…[were] a ‘wasteland’ primed for ‘reclamation’ through ‘restorative plantation’ and afforestation — recognised the importance of what today we call ‘Open Natural Ecosystems’ for wolves.”

These Open Natural Ecosystems (ONEs) consist of a range of non-forested habitats from savanna grasslands to deserts, which host a high density of “large mammalian fauna”.

What’s particularly interesting about these ecosystems is that unlike wildlife sanctuaries and other protected areas where limits are set on human habitation, they support the lives and livelihoods of pastoralists and their livestock. Understanding what was at stake, Shahi lobbied the government for years to create a wildlife sanctuary to preserve Mahuadanr’s wolves.

Finally, during his tenure as the chief wildlife warden of Bihar, he managed to eke out 63.25 square kilometres of wolf habitat and got it notified as the Mahuadanr Wolf Sanctuary. More importantly, however, he recognised the critical role villagers living in the surrounding areas and their livestock (primarily goats) played in the survival of Mahuadanr’s wolves.

“He ensured that the grazing and movement rights of local villagers shall not be impeded by the creation of this wolf sanctuary (legally a wildlife sanctuary), while simultaneously ensuring protection of the habitat, especially from hair-brained wasteland reclamation exercises,” says Kazmi.

Raza argues that rather than notifying an unbroken continuous block of forest land as a wildlife sanctuary, Mahuadanr sanctuary was created by focusing on wolf denning sites, which meant that the sanctuary is discontinuous and consists of many enclaves.

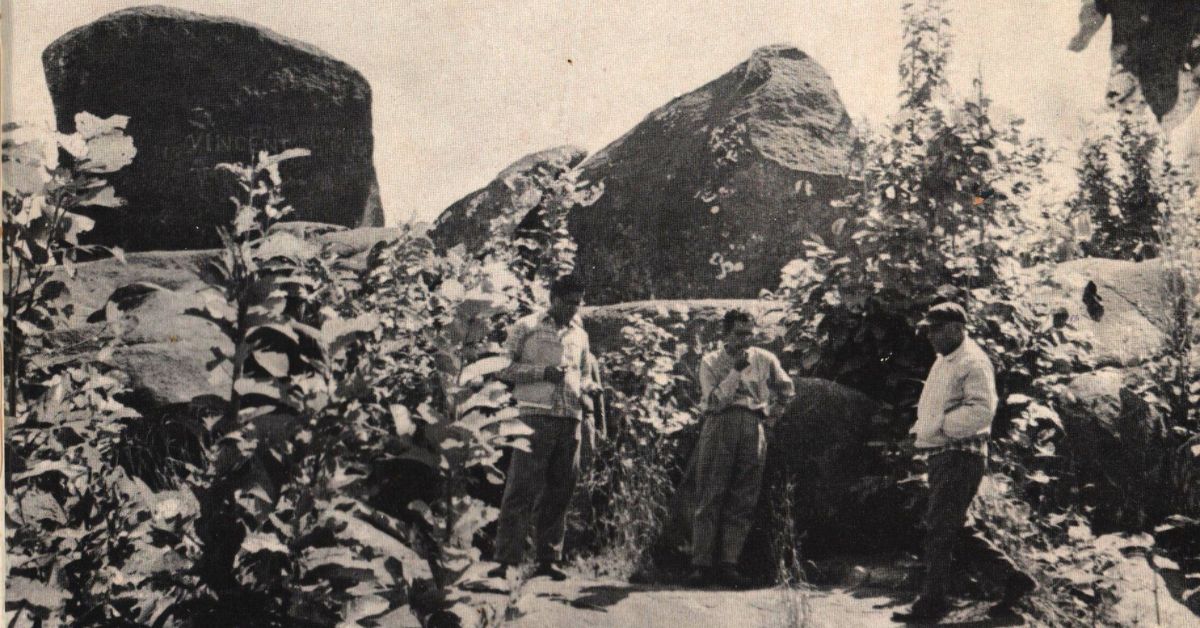

“These dens were identified and protected. One of his favourite dens was ‘Urumbhi’, a cluster of large rocks where he spent many days and nights — both during service and even after his retirement — observing ‘his’ wolf packs, their breeding and overall ecologies,” says Kazmi.

“This system allows villagers to graze their goats and move about in the landscape through the discontinuous patches of land that are not part of the sanctuary. On a managerial level, he simply had the staff instructed to manage the sanctuary in a way that did not create hostility against wolves due to restrictions on the resource use of villagers. That mantra continues to this day in the sanctuary’s management,” he explains.

Why was it important to not impede their grazing rights?

The most obvious was that the wolves of Mahuadnr are highly dependent on small livestock such as goats, sheep, pigs, and occasional poultry belonging to the villagers. Having these in the landscape was essential to sustain them.

“On the other hand, he didn’t want villagers to develop hostility against wolves due to restrictions on their resource use because that would likely end in the wolves being killed off by the people. Since Mahuadanr did have a history of angry villagers sometimes smoking out wolf dens to kill pups as well as occasionally poisoning wolves, he didn’t want to take any risks,” he adds.

Shahi’s death in 1986 was earlier seen as a devastating blow to Mahuadanr, given how forest administrators left it uncared for.

Fast forward to 2013, when Kazmi says he began “retracing some of Shahi’s trails in Mahuadanr using his old field notes”. Much to his delight, he found “wolf signs, spoor, and trails all across his [Shahi’s] erstwhile field sites”.

These wolves had survived largely because of the goat-rearing pastoralists who could still freely access the Mahuadanr valley. Shahi’s decision to ensure their grazing rights had paid off.

Regardless, it’s not as though these wolves and villagers shared a totally peaceful co-existence. There have been instances of some disgruntled villagers poisoning adult wolves and killing their pups by smoking their dens, both during Shahi’s tenure in the service and thereafter.

“However, in totality, the wolves had managed to hold their own and the herders mostly did not mind a goat or a pig being taken off by the wolves. Wolves adapted, and villagers tolerated their occasional raids. ‘Don’t you feel angry when wolves snatch away one of your goats?’, I had once asked a goat-herder on the banks of Burha river in Mahuadanr. ‘No. The wolf takes his share. After all, he too needs something to survive,’ he nonchalantly replied,” recalls Kazmi.

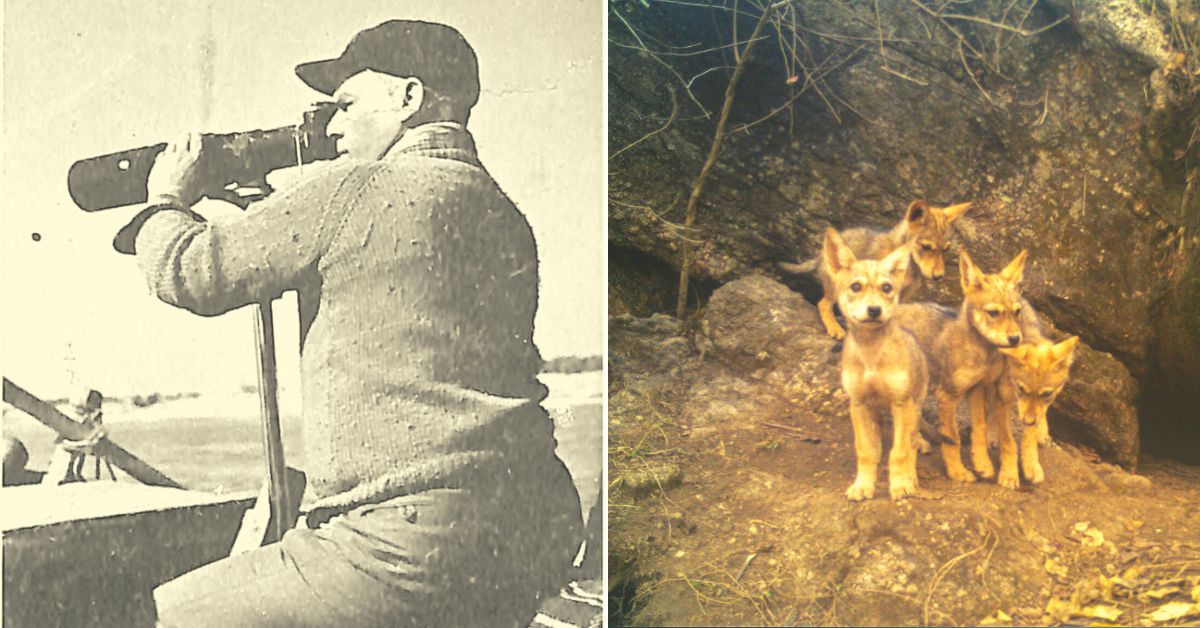

In 2012, however, forest department officials at the neighbouring Palamau Tiger Reserve, who manage the wolf sanctuary, initiated the process of camera trapping and monitoring of dens where Mahuadanr’s wolves reside. Thanks to camera trapping, the first images of these elusive wolves were revealed since Shahi took those photographs back in the 1970s.

Earlier this year, forest authorities released images of a new generation of Mahuadanr wolves from the dens of Urumbhi. This is where Shahi first observed these wolves more than 50 years ago, which led him to the path of notifying this sanctuary.

Mukesh Kumar, deputy director (South Division), Palamau Tiger Reserve, notes that the number of wolves at the Mahuadanr sanctuary has crossed 100 as per the latest annual census.

“It’s important to note that their pups are born between the months of December and February. During these months, the grey wolves reside in dens/caves where they can raise their young, so we ensure that public disturbance and interference are kept at a minimum. This requires greater vigilance from the forest department in terms of foot patrols and we advise local villagers to not loiter around these dens, particularly at night when mothers train their pups to navigate this habitat,” says Mukesh Kumar.

Also, to offset the occasional loss of livestock to villagers, the forest department has engaged them in eco-tourism projects like the one in Lodh Falls, the highest waterfall in Jharkhand, which lies in the Mahuadanr Wolf Sanctuary.

“In the last two years, eco-development committees of Lodh and other nearby villages have taken control to manage this site and surrounding forest areas. Currently it is peak tourist season and locals are earning a lot on a daily basis. This initiative has allowed them to connect with the conservation effort. Another important initiative is to raise awareness about the state of these wolves among local villagers. Today, they appreciate and understand the fact these wolves are as endangered as tigers. Raising awareness has also corrected a common misconception among local villagers that these wolves are ‘child lifters’,” he adds.

“Wolves are the top predators of the scrub, open and grassland ecosystems in India and are critical indicators of the health of these ecosystems. As explained earlier, wolves and the health and sanctity of these ecosystems go pretty much hand in hand. As soon as these ecosystems start declining, wolves are among the first to disappear,” says Raza.

What makes these Indian grey wolves special?

According to Vanak and Godbole, “Indian grey wolves are unlike their European and American counterparts. They are smaller, leaner, [and] highly adapted to the hot, arid plains of the Indian subcontinent. They are, along with the Tibetan wolf found in the Himalayas, among the oldest wolf lineages in the world. Scientists have given the Indian wolf its own sub-species status, Canis lupus pallipes, and some have argued that it should be its own unique species. If the Indian wolf were to disappear, this ancient evolutionary lineage would be forever lost, and India’s savannas would be bereft of both their top predators.”

All-round conservationist

Shahi arrived on the scene at a time when more than two-thirds of undivided Bihar’s forests were privately owned by royals and wealthy zamindars.

According to Bittu Sahgal, editor of Sanctuary Asia, “A product of his time, [he] was trained by the British who then considered trees to be worth no more than the amount their timber fetched. And wild animals, he was taught, had no greater value than their pelts, ivory, horns, or the ‘sport’ they offered to hunters. When narrating stories of his earlier life to me, of trees felled and tigers shot, his eyes would mist over — “I wish someone had introduced me to the joys of the camera earlier.”

Following Independence, however, the government of an undivided Bihar took over the management of these forests through the Bihar Private Forest Act, 1947. The legislation was passed in the leadup to the Zamindari Abolition Act & the Land Reforms Act immediately after independence.

Unlike other states, the forests of undivided Bihar were unique in the sense that an overwhelming bulk was part of the estates of various large zamindars. Through the 1947 act, the government confiscated all these forests from the owners and turned them into government forest land.

Shahi, who first joined the Bihar Forest department in 1942 as a timber supply officer, was among the cadre of forest officers hired to prevent the large-scale destruction of these forests by their owners, who had refused to accept this new piece of legislation.

His exceptional work in fulfilling this particular assignment earned him an out-of-turn promotion. His rise in the forest service was meteoric — in 1960, at the age of just 43, he became the first chief conservator of forests, the youngest in the country. He would go on to serve as a forest officer with distinction till his retirement from service in 1976.

Kazmi argues that after the passage of the law, “Expectedly there was a huge pushback from powerful landlords. Shahi was one of the most prominent officers of the state tasked with implementing this law in letter and spirit. Slowly, he managed to get the forest department to establish full control over these former private forests.”

One such step, which highlighted his foresight and ability as a forest officer, was to cancel all shooting blocks in undivided Bihar in 1968, a whole two years before a similar nationwide ban on hunting was enforced in 1970.

“Also, all major PAs (protected areas) of Bihar and Jharkhand were either created during his tenure as Bihar’s chief wildlife warden or immediately thereafter as a follow-up on the proposals already passed during his time in office. In Jharkhand, some of these include the Palamau WLS (now part of Palamau Tiger Reserve), Hazaribagh WLS (wildlife sanctuary) and Lawalong WLS, Dalma WLS. In Bihar, they include Valmiki WLS (now part of Valmiki Tiger Reserve), Bhimbandh WLS, Gautam Buddha WLS, and Kaimur WLS among others,” says Kazmi.

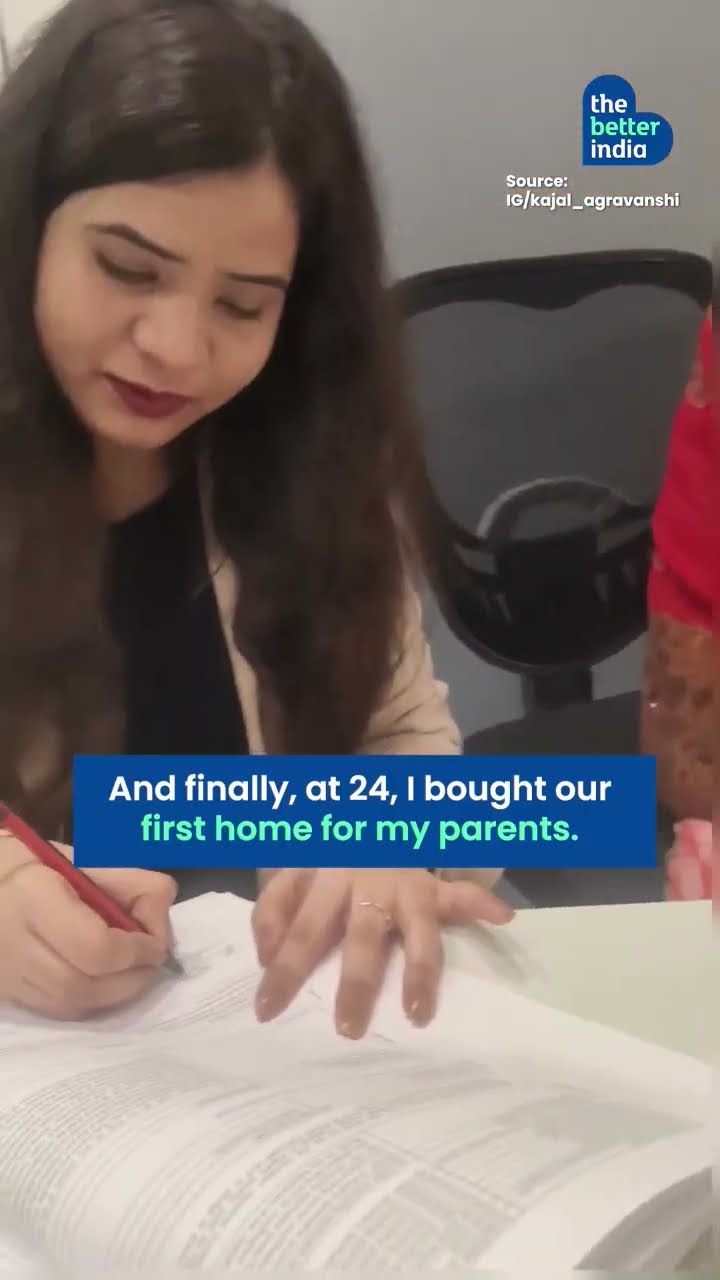

Towards the end of his career in the service and post retirement, he took up his passion in wildlife photography to whole another level.

Spending nights in hide-outs and machans in various forests of Bihar trying to capture elusive species like leopards, tigers, grey wolf and other wildlife in his state. His much-acclaimed photographs of little known grey wolves in the Mahuadanr valley in Palamau were, for the longest time, the only photographic records of the species from the state. He was also the first wildlife photographer to take portraits of Indian wolves hunting (a baited goat), in the early 70s.

Besides photography, he was also a prolific writer, and his book ‘Backs to the Wall: Saga of Wildlife in Bihar’ till this day remains the only book written on the wildlife of present-day Bihar and Jharkhand, more than 40 years ago.

P K Sen, former director of Project Tiger, who passed away last year due to COVID-19 and knew Shahi well, once said, “S P Shahi’s work in Palamau and his meticulous documentation of its wildlife was a very key reason that this forest was chosen as one of the first nine to be declared as tiger reserves in 1973. Few people realise that as far back as 1968, he had all shooting blocks in the state of Bihar cancelled, two years before the Government of India took this step in 1970. What triggered this determination was the remorse he felt when he himself shot a tigress and was haunted by the senselessness of the act.”

Bittu added, “Not surprisingly, after realisation struck, he was like a man possessed. Having given up the gun for the camera he began to spend extraordinary amounts of time in the wilds of his beloved Bihar, often spending night after night in make-shift hides, waiting for a chance to photograph a wolf or tiger. He also rededicated his life to the proposition that new, young forest officers should not be contaminated by faulty learning that placed nature at a discount. Towards this end he published articles, scientific papers and proceeded to give lecture after lecture in an effort to wean future decision makers away from the ecological quick sands of the past.”

(Edited by Divya Sethu)

Additional Sources:

‘India’s missing wolves’ by Abi T Vanak and Mihir Godbole; Published on 20 May 2022 courtesy The Hindu

‘S.P. Shahi – (1917-1986)’ by Bittu Sahgal; Published in February 2011 courtesy Sanctuary Asia

‘Conservation in east-central India’ by Raza Kazmi; Published courtesy India Seminar

Images courtesy Twitter/Raza Kazmi and Mukesh Kumar

‘Mapping the distribution and extent of India’s semi-arid open natural ecosystems’ by MD Madhusudan and Abi Vanak; Published on 25 July 2021 courtesy ESSOAr

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.