When the Women of Rural Bengal Challenged the British With Swadeshi Songs

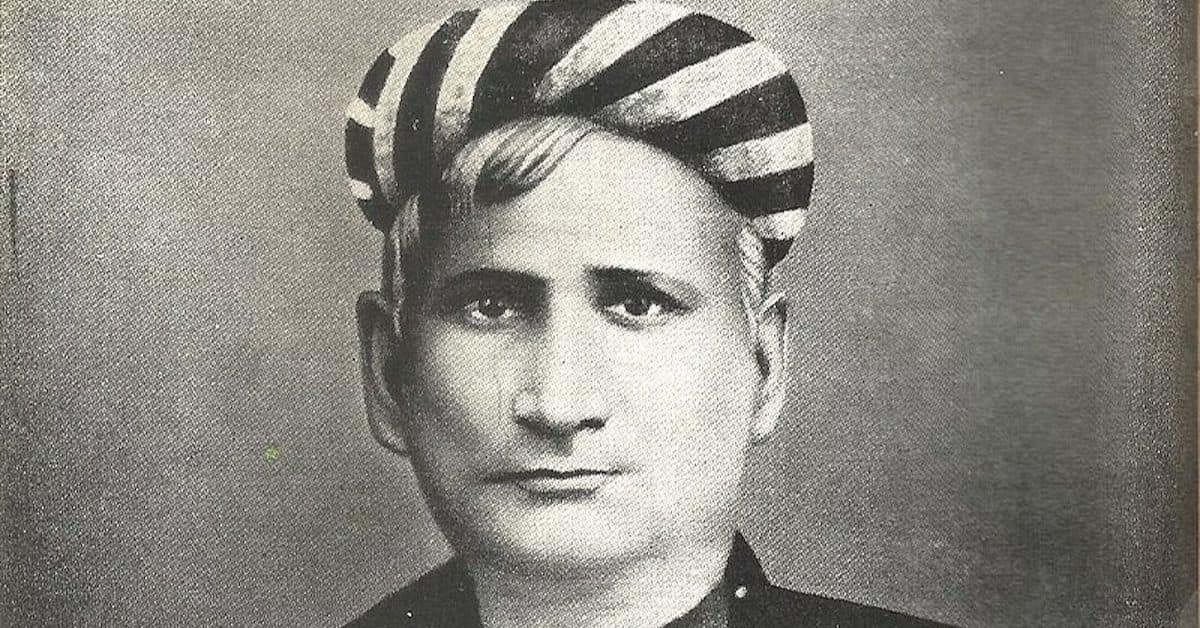

Educator Chandra Mukhopadhyay, who has spent decades documenting rare folk songs sung by women, narrates how rural women of Bengal used music to challenge the British Raj during the Swadeshi movement.

In the early 1900s, as the Indian independence movement grew and the Swadeshi Movement gained momentum, the music of the land, too, began reflecting its response to the changing socio-political landscape.

While Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Vande Mataram became the anthem for political movements, devotional songs like Raghu Pati Raghav Raja Ram, popularised by Gandhi, became particularly popular during the Salt Satyagraha in 1930.

In Bengal, the slogan of Vande Mataram reached even the remotest villages, which otherwise had no direct connections with the centres of the freedom struggle, explains Kolkata-based educator Chandra Mukhopadhyay. In particular, the clarion call mobilised the women of these villages, who had their own ways of expressing their devotion to the motherland.

“Women in every village in Bengal could be heard singing it, helping spread the Swadeshi fervour in the region,” Chandra explains in this video.

“These women didn’t sing patriotic songs or compose songs for the freedom struggle. But the slogan Vande Mataram, which had spread all through Bengal, reached them as well,” Chandra notes in conversation with The Better India.

The idea of using only homegrown products and rejecting foreign goods resonated with them, and they started encouraging the idea of wearing indigenous clothes, bangles, vermillion, and so on. While their songs were still about marriage or agriculture, they quickly made space for the phrase Vande Mataram as well.

Chandra has spent many years extensively researching and documenting the folk music of the undivided Bengal region, travelling to districts like Murshidabad, Cooch Behar, Jalpaiguri, and Bankura, among others, and learning about this women-centric music tradition.

Today, Mukhopadhyay has a collection of about 6,000 folk songs. Her 2022 book Narir Gaan Shromer Gaan collects together 400 of these songs, and she’s now working on her next one.

A long journey

It was a day some time in the 90s — when she was teaching English at Khalisakota Adarsha High School in a refugee colony in Kolkata — that Chandra heard drums and an accompanying tune drifting in the wind.

Curious, she asked her students what this music was, and they told her it was a traditional marriage song, usually sung by women of Dhaka, who belonged to artisan communities that make earthen pots and utensils. These women belonged to Bangladeshi families who had migrated to India, and were keeping their culture and traditions alive in this way.

The students guided her to the residence where the song was coming from, and she met Bedana Pal and Ashalata Pal, who sang her the song Laal Pagudi Bandhe Mathay Amar Krishna Chale Mathura (My Krishna Goes to Mathura Wearing A Red Turban).

These songs belonged to a historic line of oral tradition, but were nowhere to be found preserved in texts. Chandra worried that the younger generation might never be privy to these, and that the tradition was starting to disappear.

“Popular traditional music is devoid of life itself. The life we lead is not depicted in those songs. It’s all about lovemaking, stars, and so on. But the ground reality is not reflected. Folk songs are born from the soil, and they talk of the soil,” Chandra says.

Through this music, the women talk about their work, joys and sorrows, any experiences they’ve had, compose music for special occasions, and more. “All over the world, women’s labour is not recognised as work. But these women, they recognise their work — through composing these songs.”

These songs are rich sources of a sidelined history and culture, preserving the way of life of rural women for generations. They contribute to undivided Bengal’s socio-cultural and music landscape, and shed light on these women’s histories.

A literature student, Chandra always had a deep interest in music, having trained in classical music and Rabindra Sangeet for a while.

“The music I was learning was for the elite, it was drawing room music. There was a craving within me to know what there was for common people, how their lives were narrated,” she says.

In 1975, Chandra came across philosopher Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya’s book Lokayata: A Study in Ancient Indian Materialism, which she says changed her worldview. “Usually Indian philosophy is based on idealism. But this book belonged to the materialistic school of philosophy, seeing life from a materialistic point of view.”

The book informed her that in ancient times, there was a connection between food gathering and songs, with several shlokas about perishables like rice. “There were songs for food in the days of the Upanishads and earlier,” she notes. These songs essentially expressed their way of life, service as rich resources and records of the time.

“The songs were so different. Very vibrant in tune, rhythm, and outlook. They talk about the mundane things of life, which are excluded from the mainstream composition of songs. The women are very upright, frank, and lively, they tell us everything in their songs.”

‘Vande Mataram’ – expressing independence through music

These Bengali folk songs belong to a rich, oral tradition, and are sung by rural women. “They are not literate, but they can sing for hours. It’s all preserved through the community in their collective memory,” Chandra says.

While travelling and collecting folk songs, Mokhopadhyay was also educating herself about the language and literature of different Bengali districts. “Through reading books about history, anthropology, sociology, and literature, I learnt that women singing is an ancient tradition prevalent all over the world.”

These songs weren’t sung as a form of entertainment for others. They were accompaniments to the women’s lives, and talk about all types of things, from a girl’s first menstrual cycle to a woman giving birth and caring for a child, and from the agricultural activities they carried out to songs sung during ceremonies like marriages. “We can deduce from these that women weren’t homebound and that they sang their own songs in public.”

Besides attesting to their involvement in the freedom struggle, these songs also challenge the traditional portrait of women as shy, inexpressive, oppressed, and inactive, as recorded in traditional literatures and histories. “These women are not that type. They frankly expressed their sorrows, joys, sexual urges, sexuality, anger, disgust, ill treatment.”

“They sing for protest and social responsibility. They were powerful, socially responsive women. Picketing melodiously is their creativity. They were not secondary citizens of society.”

Here are five melodies that Bengal’s women used to express their patriotism during the peak of the freedom struggle:

1. Boile Vande Mataram,

Kolkatate bhoire go anlam kalotilar jal

(We all chant Vande Mataram, while fetching water from holy Kalitaka)

This is sung by the weaving community of Comilla, a district of east Bengal. The marriage song talks about chanting Vande Mataram while carrying out a ritual, which included going to collect holy water.

2. Paati bichhao maaj ghare, Vande Mataram boile sita sajao maar kule, Vande Mataram boile

(Sing Vande Mataram while spreading the mat on the floor and dressing up Sita [the bride] on her mother’s lap)

This song is sung by all the artisan communities of Faridpur, a district in Bangladesh, and talks about chanting the phrase when dressing the bride up for marriage.

3. Paatite dhalia chaal, chaal kare uljhaal sabe bole Vande Mataram

(Sing Vande Mataram in unison while you sort out the grains of rice)

Another marriage song, this one originates from the communities of Dhaka, and discusses saying the phrase when separating rice grains as part of marriage rituals.

4. Swadeshi sindur diye korabo sajan sindurero modyi lekha Vande Mataram

(We shall decorate the bride with indigenous vermilion on which is inscribed Vande Mataram)

From Mymensingh in Bangladesh, this song has been composed by a community that creates earthen utensils and focuses on using homegrown products like vermillion, which ring of independence instead of relying on foreign goods.

5. Deshi sajan chamotkar, paro bondhu akbar bilalite mou diyo na,

Gandhi Rajar maan mero na

(Put our indigenous clothes that are beautiful

Oh friend, don’t go for foreign ones.

It is a call from Gandhi, the king!

Don’t insult him anyway)

From Sylhet’s weaver community, this song talks about following Gandhi’s call to use indigenous clothes and reject foreign items.

Edited by Divya Sethu

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167