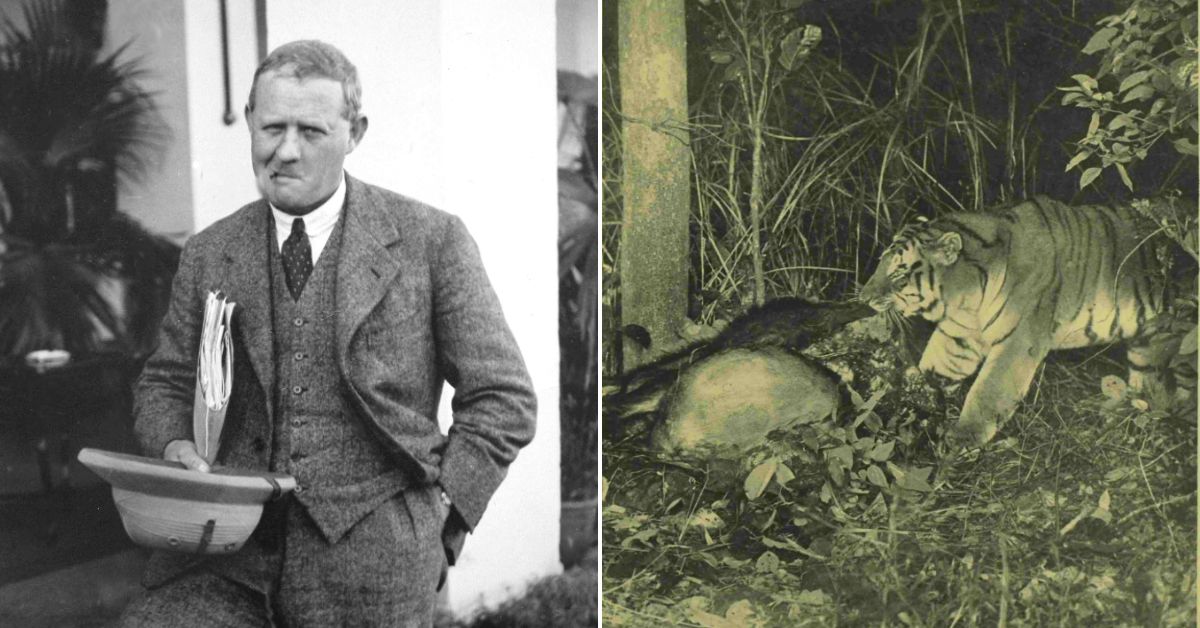

How a Forest Officer Clicked India’s 1st Photo of a Tiger in The Wild

Frederick Walter Champion is considered the 'Father of Camera Trap Photography'. Conservationists today use this method to calculate tiger census and monitor their movements.

Frederick Walter Champion, an ex-soldier in the British Indian Army, an officer of the Imperial Forestry Service [Indian Forest Service] and a pioneering conservationist, took the first photograph of a tiger in the wild in India. A 1921-batch officer, Champion served in the United Provinces (corresponding to approximately present-day Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand) until 1947 and rose to the rank of deputy conservator of forests. A pioneer of the camera trapping technique, he was also credited as a pioneer of wildlife photography in India by Jim Corbett.

Speaking of Corbett, Champion’s undying commitment to conservation inspired him to give up the gun for the camera, and together, they became the founding members of India’s first national park established in 1935, which was renamed Corbett National Park in 1957.

Born on 24 August 1893 in Surrey, England, Champion grew up in a family of nature lovers with his father George Charles Champion, an entomologist. His brother, Sir Harry George Champion, a forester, was credited later on with creating a classification of the forest types of India.

Champion first came to India in the early 1910s, serving in the East Bengal police department until 1916, following which he was commissioned into the British Indian Army Reserve of Officers (Cavalry branch). After World War I and his retirement from the army in the early 1920s, he joined the Imperial Forestry Service. Unlike other officers of his era, he detested the idea of shooting animals for sport and preferred documenting them through wildlife photography.

Tripwire photography

Even before joining the IFS, Champion had tried to obtain an image of a tiger in its natural habitat. As wildlife historian Raza Kazmi noted in a Twitter thread, “It took him 8 long years to finally get these images.” Taken in the Kumaon forests, these images were first published on the front page of ‘The Illustrated London News’ on 3 October 1925 with the accompanying headline, “A Triumph of Big Game Photography: The First Photographs of Tigers in the Natural Haunts”.

Two years later, he came out with a book titled, ‘With Camera in Tiger-Land’. This book set new precedents for publishing “photographs of wild animals, just as they live their everyday lives in the great Indian jungles, away from the every-destroying hand of man” instead of ones marked by these majestic animals running from beaters, about to be and eventually shot by hunters.

The pain-staking technique he employed to shoot these photographs was called ‘trip-wire photography’. As Raza Kazmi explains, “A tiger (or any other animal) tripped on a wire carefully concealed below his usual walking path resulting in him taking his own image, usually by the night as the flashes connected to the wire went off simultaneously.”

Champion described this process in a letter accompanying the piece in ‘The Illustrated London News’, “These photographs are quite unique, no satisfactory photographs ever having been taken before, to my knowledge, of tigers in their native haunts.” Going further, he stated, “The flash is so sudden that he probably takes it for a flash of lightning.”

The implications of this technique have been far and wide. Further refined in the subsequent decades, this technique is today known as ‘camera trap photography’. Conservationists today use this method to calculate tiger census and monitor their movements.

As Mahesh Rangarajan, a professor of history and environmental studies at Ashoka University, states in this column for The Telegraph, “Of the 200 camera traps placed by Champion, tigers came by on only 18 occasions. In all, he had 11 shots of nine individuals, but this was enough to prove how each animal had distinct stripe patterns. This was a path-breaker in every sense. Over the last three decades, scientists the world over working with far more advanced cameras and aided by software can tell a tiger by his or her stripes. It is now a widely used technique worldwide, and its pioneer was a deputy conservator of forests nearly a hundred years ago.”

To give us some context on how difficult this process was for Champion, K Ullas Karanth, a leading tiger expert based in Karnataka, wrote this in his introduction to ‘Tripwire for a Tiger, Selected works of FW Champion’:

“As I struggled with my camera traps, trying to photograph tigers to get a more accurate count in the late 1980s, using 35mm SLR cameras and tripwires, I marvelled at Champion’s tenacity with his archaic camera traps, 60 years earlier. I was astounded to learn from his accounts that, after 30 years of using camera traps in prime tiger jungles, Fred Champion managed to get just nine high-quality photos of tigers.”

For photographer friends, Champion even gave what we today call the EXIF details:

“…although the photograph of the tiger pulling his kill was taken at 1-50 sec. on a special rapid plate; suitable exposures are from 1-150 to 1-200 sec., with f6.8 on an ultra-rapid plate…” pic.twitter.com/q4Ro1PCSn5

— Raza Kazmi (@RazaKazmi17) June 8, 2022

Legacy as conservationist

Besides his role as the ‘Father of Camera Trap Photography’, Champion also played a pivotal part in leading the conversation around wildlife conservation at a time when British officials took pride in big game hunting. Concerned about the dwindling number of tigers due to hunting, he allotted “shooting blocks where there were likely to be no tigers for hunters to shoot,” wrote Rangarajan. Also, he strongly advocated for limiting gun licences, preventing motorcars from entering reserved forests and reducing cash rewards for killing wildlife.

For example, the Shivaliks, where Champion had served with real distinction, contained shooting blocks of the governor-general. Before Corbet came across Champion’s works including ‘With a Camera in Tiger-Land’ (1927) and ‘Jungle in Sunlight and Shadow’ (1934), he would organise big game shoots for top officials of the British Indian administration.

When India attained Independence, however, C Rajagopalachari (Rajaji), a freedom fighter and the second and last governor-general of India, changed things.

“It is said that when Rajaji, the newly appointed Governor General, was invited for a hunt but he was so impressed by the biological diversity and plethora of wild animals in the area that instead of hunting, he suggested the creation of a wildlife sanctuary in the area,” notes this description on the Rajaji Tiger Reserve website. Thus, out of the shooting blocks in the Shivaliks, a sanctuary was carved out in 1948 and today it’s known as the Rajaji National Park, which “extends over the Shivalik Range from the Dehradun-Saharanpur road in the north-west to the Rawasan River in the southeast, with the Ganges dividing it into two parts”.

Post 1947, Champion left for East Africa, where he said in a letter to British tea planter and naturalist Edward Pritchard Gee, “Animal photography here is too easy”. He was nostalgic “for my friends, the tigers of India, which can at no time be photographed easily.”

But this didn’t stop him from adding valuable inputs to the global discourse on wildlife conservation. Noting that “every creature has its place in nature’s balanced scheme of wildlife”, he argued that predators like the leopard, wild dog or jackals weren’t bloodthirsty animals who deserved to be shot down and that the best course of action would be to leave them alone.

Speaking of other animals, his book ‘The Jungle in Sunlight and Shadow’ explores the forests he witnessed in India beyond the tiger-like the scaly ant-eater, honey badger, swamp deer and the pangolin, amongst others. He would also go on to take some of the first night-time photographs of wild leopards, sloth bears, dholes, etc.

At the age of 76, he passed away in 1970, but the legacy he leaves behind is remarkable. A man ahead of his time, he advocated for a strong forest department in India. He believed they had a duty and responsibility to protect wild animals like the tiger and their forest habitats.

Some argue that Project Tiger, which Indira Gandhi launched as prime minister back in April 1973, is in many ways the legacy of Champion’s work in India. In fact, Kailash Sankhala, the first director of Project tiger and a legendary conservationist, once said that if tigers had been given a vote, the Corbett National Park would have been named after Champion.

If you want to understand what real wildlife photography feels like, here’s what Champion said: “Such pictures, hanging on one’s walls in subsequent years, bring back vividly, as no skin or head can ever do, what may have been the most thrilling moments of one’s life. Surely, looking at the photographs, one can half-close one’s eyes and see, not photographs, but real scenes.”

Sources:

‘With A Camera In Tiger-Land’ by FW Champion; Published in 1927; courtesy Digital Library of India

‘The other hero: In Jim Corbett’s shadow’ by Mahesh Rangarajan; Published on 13 October 2020; courtesy The Telegraph

‘Origin of Rajaji Sanctuary’ courtesy Rajaji Tiger Reserve

‘Tripwire for a Tiger: Selected works of F.W. Champion’; Published in January 2012 by Rainfed Books; Edited by James Champion

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.