‘Asia’s 1st Grandmaster’ Was An Unsung Chess Genius Who Shattered Many Glass Ceilings

At a time where chess was a ‘rich man’s sport’, Mir Sultan Khan established himself among the greatest natural players of modern times.

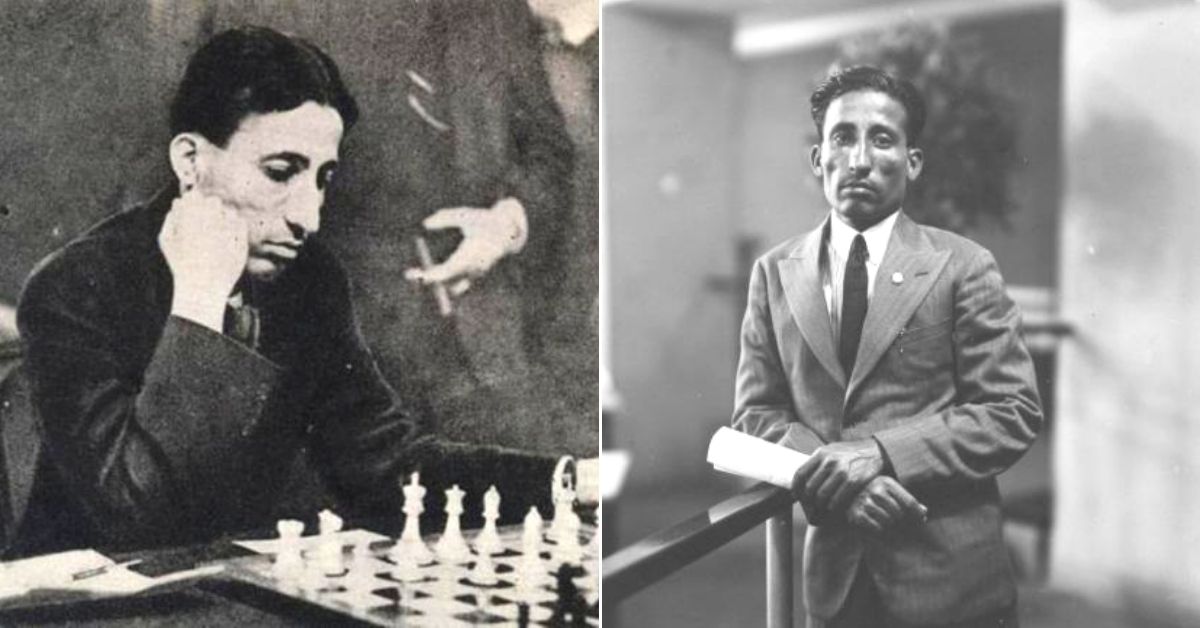

In the foreword to Grandmaster Daniel King’s book Sultan Khan – The Indian Servant Who Became Chess Champion of the British Empire, Indian chess legend Viswanathan Anand wrote, “Even if the world that Sultan Khan inhabited seems distant, he should be remembered as the first Asian to break through into the upper echelons of the international chess scene.” (Above images of chess genius Mir Sultan Khan courtesy chesshistory.com)

Through the late 1920s and early ‘30s, Mir Sultan Khan took the world of chess by storm. In an international career that barely spanned five years, Sultan won the prestigious British Chess Championship in 1929, 1932 and 1933, and defeated a series of ‘White’ masters of the game including Akiba Rubinstein, Salo Flohr, José Raúl Capablanca and Savielly Tartakower.

Called a ‘genius’, the ‘greatest natural player of modern times’ and ‘Asia’s first grandmaster’ on different occasions, Sultan Khan’s remarkable story has been largely forgotten.

Emergence of a prodigy

Born in 1903 in the village of Mitha Tiwana, Khushab district (present-day Pakistan), Sultan came from a family of pirs (Sufi spiritual guides) and landlords belonging to the Awan tribe, which traced their lineage all the way back to the Mughal era. A young Sultan learnt how to play chess from his father Mian Nizam Din. As a child, he would play regularly with his brothers.

By his late teens, however, Sultan began competing against landlords and other chess enthusiasts in the nearby city of Sargodha. With little responsibilities at home, he honed his craft playing an Indian form of chess, which had considerably different rules back then as compared to their Western counterpart. By 21, he was considered the best in the Punjab Province of undivided India. His stellar talent caught the attention of wealthy landlord Sir Umar Tiwana, a known loyalist of the Empire who derived his fortune from British patronage.

A fellow chess aficionado, Sir Umar was dazzled by this young man’s ability. Fancying himself as a patron of the arts and sports, he made an offer to the talented Sultan.

In exchange for a stipend, board and lodging, Sultan was requested to set up a chess team at Sir Umar’s estate in the neighbouring village of Kalra. Training at Sir Umar’s estate, Sultan went on to compete in the 1928 All India Chess Championship which he won with a stellar performance by only dropping a half a point across nine games.

In the following year, Sir Umar took Sultan to London, where the latter was inducted as a member of the Imperial Chess Club. It was here where he learnt to play the Western form of chess, which had considerably different rules from the Indian form of the game. Also, one must remember that at the time, chess was a rich man’s sport. A player would need money to pay the expensive fee for club membership in participation in tournaments.

Chess master Sultan

Despite limited experience in the Western format, it’s remarkable that in the same year that he arrived in England, Sultan went on to win the British Chess Championship held in Ramsgate. Given the fact that a large segment of the world was under the control of the British Empire back then, this particular tournament held the status of a world championship. Once he won, invitations to play came from all over the United Kingdom and Europe. However, he first decided to go back home in November 1929 before coming back to Europe in May 1930.

Upon his return to Europe, Sultan played in a variety of tournaments including the Scarborough Tournament, the Hamburg Olympiad, and the Liege Tournament.

Among his biggest scalps in these tournaments was Victor Soultanbeieff, a Belgian chess master, in Liege. On 30 December 1930, however, Sultan scripted his most famous victory at the 11th Hastings Christmas Chess Festival in England against defending champion José Raúl Capablanca, a Cuban genius who was the world chess champion between 1921 and 1927, and considered one of the greatest chess players of all time. Sultan outfoxed him in a game considered by certain chess aficionados as a masterpiece in chess strategy and tactics.

“The fact that even under such conditions he succeeded in becoming a champion reveals a genius for chess which is nothing short of extraordinary,” wrote Capablanca years after meeting Sultan Khan at the chessboard. In the following year, he also defeated Savielly Tartakower, a Polish-French chess master, in a 12-game match which finished 6.5 to 5.5.

The same year, he would go on to participate in the Prague International Team Tournament, where among other opponents, he defeated the likes of Czech player Salo Flohr and Akiba Rubinstein, a Polish chess master and pioneer of the game. Rubinstein is considered by some chess historians to be one of the greatest players to have never become World Chess Champion. He also drew his match with Alexander Alekhine, the reigning world champion.

The following two years (1932 and 1933), saw Sultan winning the British Chess Championship, while also making a mark for himself in other tournaments across Europe like the Cambridge Tournament (1932), Berne Tournament (1932) and Folkestone Olympiad (1933).

As a chess player, Sultan’s strengths lay in what is called the middle game and the end-game. In fact, he is considered a master of the end game, who could come out of very difficult situations without losing any control of his emotions.

“His playing style was also dubbed the ‘Wrath of Khan’ for, despite his impassionate exterior, his chess game was bold and masterful. This is most emphatically seen in his victory over Capablanca, which has gained the status of a classic in the chess world,” wrote Ather Sultan, Sultan’s son, and Atiyab Sultan, his [Sultan’s] granddaughter, in a column for Dawn.

His game, however, had its weaknesses, as Daniel King points out, “First of all, his openings were terrible. That’s because he didn’t grow up playing western chess, although he did have some tuition and he learned some openings. He played systems; he didn’t really play variations. And sometimes he just made horrible blunders in the opening.”

By the beginning of 1933, Sir Umar had left the continent alongside Sultan after attending the Round Table conferences between Indian representatives and the British Empire. With Sir Umar no longer going on his European voyages, Sultan didn’t have the requisite resources to pay for his travels to the continent and pay the hefty match fees needed to play tournaments.

Although Ather Sultan and Atiyab note in their column that Sultan spent the rest of life “cultivating his ancestral farmlands”, a report in The Tribune notes otherwise.

“The Tribune newspaper archives reveal that Khan was active till 1940. News reports said he played simultaneous matches with 40 players just after he landed in Mumbai after making it big in the UK. Another report said he played simul tournaments against 20 players, and won all games. That tournament was held at Dera Ismail Khan in February 1940. Khan won the Governor’s Trophy for his feat,” notes the report published on 6 September 2020.

At the time of Partition, Sultan decided to stay back in present-day Pakistan, where his wife and family of five sons and six children resided. He passed away in Sargodha in 1966 and remains buried on his estate in Bhalwal. The legacy he leaves behind is quite extraordinary.

Even though chessmetrics.com, which calculates historical chess ratings, ranked Sultan as No. 6 in the world at his peak, global chess authorities at the FIDE have forgotten him. Back in 1950, FIDE, the world chess governing body, awarded titles of International Grandmaster and International Master to recognise the distinguished careers of retired chess legends. While the likes of Rubinstein and Tartakower have received the title of Grandmaster, Sultan hasn’t.

Sources:

‘Sultan Khan: The Indian Servant Who Became Chess Champion of the British Empire’ by Daniel King, Published on 1 March 2020

‘Chess: The Wrath of Khan’ by Ather Sultan and Atiyab Sultan for Dawn, Published on 17 May 2020

‘The (Political) Story Of ‘Extraordinary Genius’ Sultan Khan’ by Peter Doggers for Chess.com, Published on 2 May 2020

‘Sultan Khan, the unsung king of chess’ by Jupinderjit Singh for The Tribune, Published on 6 September 2020

‘Sultan Khan’ by Edward Winter for chesshistory.com, Published in 2003

(Edited by Divya Sethu)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.