This Punjabi Businessman Changed The Lives of Millions of Indians in America

J J Singh, an Indian businessman in New York, was not only a strong advocate for India’s freedom struggle, but also played a key role in shaping American politics and helping millions of Indians get citizenship in the US.

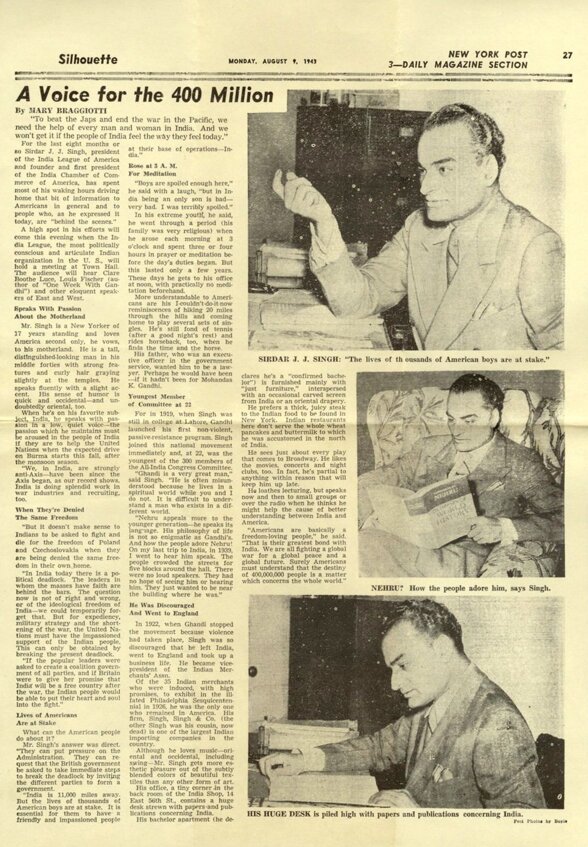

In the iconic photo of United States president Harry Truman signing the Luce-Celler Act of 1946 into law, one can see Jagjit Singh, a successful businessman and lobbyist, standing to his left. (Image above of Singh, third from right, observing President Harry S Truman signing the Luce-Celler Act of 1946 courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

The signing of this piece of legislation granted citizenship rights to the 4,000-odd Indians already residing in the US, and set a quota allowing 100 Indians and 100 Filipinos to immigrate per annum.

It was the culmination of a successful struggle by Indians residing in America to overturn the US Supreme Court’s ruling in the 1923 United States vs. Bhagat Singh Thind case, which effectively denied naturalised citizenship to them, as well as the 1924 Immigration Act passed by Congress barring immigration from Asia. After the ceremony, president Truman handed over the pen he used to sign the Luce-Celler Act into law to Jagjit Singh, who was popularly known as JJ Singh.

Today, that pen has been passed on to his granddaughter Sabrina Singh, who served as US Vice-President Kamala Harris’ deputy press secretary up until last month, before resigning to join the US Department of Defense.

It was the Luce-Celler Act that paved the way for the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, a more broad-based piece of legislation eliminating the limits on the numbers of individuals from any given nation who could immigrate to the US. In other words, this 1965 law got rid of the quota system entirely, and allowed immigrant families to reunite with each other while also facilitating greater movement of skilled labour to US soil. Once signed into law, it opened the floodgates for Indians wishing to make a better life for themselves in the US.

Here’s the remarkable story of JJ Singh, who first set the ball rolling for Indian Americans.

Encountering the freedom struggle & creating wealth on foreign shores

Born on 5 October 1897 in Rawalpindi, Singh grew up in relative privilege with his father serving as a judicial officer. As a child, he accompanied his father to different parts of the erstwhile Punjab province in British India.

Things changed for young Singh following the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar on 13 April 1919. He joined the mass Non-Cooperation Movement led by MK Gandhi. But following Gandhi’s decision to abruptly cancel it in 1922 when violence broke out in Chauri Chaura, Singh grew disillusioned and left India to study law in the United Kingdom.

On foreign shores, however, his interest was drawn to apparel wear. He soon got into the business of importing silk fabrics, handlooms and other such items imported from India, and selling them abroad with assistance from his cousin. In 1926, he visited the US to present his wares at the Sesquicentennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. He would go on to open a store in Philadelphia and another fabric store on New York’s 5th Avenue.

Business was booming in New York, with the city’s fashionable crowd wearing his dresses and gowns. His success in the Indian clothing and textile business helped him enter some of the more influential circles in the city.

In other words, JJ became the model successful immigrant. By the mid-1930s, he set up the Indian Chamber of Commerce in the US as an attempt to facilitate better trade relations between his country of business and British India. But he saw how restrictions set by colonial rule was stifling India’s ability to trade and fulfil her economic potential. Also, given the nature of his business, he was keeping tabs on events in India.

During this decade, Singh also joined the India League of America comprising members of the Indian community in New York who would regularly meet at two restaurants in Manhattan. But he was not happy with the inner workings of this organisation. He felt they spent too much time discussing Indian philosophy and literature instead of actively advocating for the cause of Indians in America and at their home country.

India League of America

In December 1941, he took over and was elected president of the India League. This was the same month when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour, and the United States formally entered World War II. In the following summer of 1942, the British not only imprisoned India’s leading freedom fighters, but also launched a propaganda blitz in the United states trying to convince Americans that independence for India would interfere and eventually kill the war effort.

Singh was having none of that given his desire to see a free India. As president of the India League, he made a couple of very smart moves. First, he opened membership to influential Americans in public life across a broad range of ethnicities and causes, ranging from labour leaders in Detroit, African American activists like Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), to ordained ministers, socialists, Chinese immigrants, and even a few lawmakers. In fact, some of Singh’s closest confidantes at the time were John Haynes Holmes, a Unitarian minister, and Sidney Hertzberg, a publicist, activist, journalist and editor.

Second, he set up an office for the India League in Washington DC, where he would regularly lobby members of the United States Congress and address the influential media. During his conversations with lawmakers and the press, he would often speak about issues like the Bengal famine, horrors of British colonial rule in India, and Japanese military advancement in South Asia.

“Indians believe in the teachings of Lincoln and Washington,” Singh once said over the radio in 1942. “Indians want to be given the chance to fight and to die for freedom and democracy.”

Thanks to his contributions, the Indian League not only grew more vocal, but also grew in numbers, eventually becoming one of the de-facto voices for nearly 4,000 Indians in the US. The two main causes they advocated for were citizenship rights for India in the US, and urging Americans to support India’s cause for Independence by issuing pamphlets, newsletters and organising various events for influential decision makers in Washington.

Of course, the British responded. Their spies infiltrated the India League, while also trying to get JJ Singh into trouble with federal law enforcement agencies. Singh responded in kind by getting associates of the India League to infiltrate the British Embassy and leak damaging documents. Meanwhile, his relentless lobbying efforts were beginning to bear fruit on Capitol Hill. He was winning over members of Congress to India’s cause and citizenship for Indian immigrants.

Matters came to a head in 1944, when a columnist for the Washington Post released information that US president Franklin D Roosevelt’s representative in India, William Phillips, had in secret asked the White House to support India’s cause for Independence. Promising India freedom, he argued, would tremendously help the war effort against the Japanese.

The Washington Post columnist in question, Drew Pearson, received this information via a leak orchestrated by the associates of the India League. Singh, of course, took advantage of this information to further strengthen American support for India’s independence.

Meanwhile, Singh was also working overnight to help undo the US Supreme Court’s 1923 decision, which prevented Indians from becoming naturalised citizens. He teamed up with two members of the US Congress, Clare Boothe Luce and Emanuel Celler, and drafted a bill to undo the court’s ruling and the subsequent 1924 Immigration Act. He also brought in other influential figures like legendary scientist Albert Einstein and African American civil rights activist W E B Du Bois to support the bill that would end up becoming the Luce-Celler Act.

He would even go on to contact all his friends in the American media, contacting “every newspaper and magazine in the United States” to endorse this bill they had drafted.

Having said that, it’s imperative to note that besides JJ Singh and the India League, there were other influential Indians and organisations working towards causes close to his heart, like Tarakanath Das’s Free Hindustan, Friends of Freedom for India, India Association for American Citizenship, Mubarek Ali Khan’s India Welfare League and Anup Singh’s National Committee for India’s Freedom. But Singh’s role in advocating for Indians and India was pivotal in many ways.

Also, members of US Congress gave their assent to this bill out of political expediency as well. After all, America needed to secure Asian allies against the Japanese. That’s why you had Filipinos and Indians in the quota system.

Singh, however, would end up not taking US citizenship. In 1959, he moved back to India with his wife Malti Saksena and their two young sons. He passed away in India in 1976.

The legacy he leaves behind is for all of us to see today.

Sources:

‘One Man Lobby’ by Robert Shaplen, The New Yorker, 16 March 1951

South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA): Sirdar JJ Singh

KAMALA HARRIS AND THE ‘OTHER 1 PERCENT’ by Dinyar Patel, The Atlantic, 7 October 2020

‘The story of one man’s efforts to bring Indian-American dreams & hopes to life’ by Anu Kumar, Scroll.in, 30 July 2020

(Edited by Divya Sethu)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.