When a Rural Newspaper for Farmers Became India’s Leading Voice Against the British

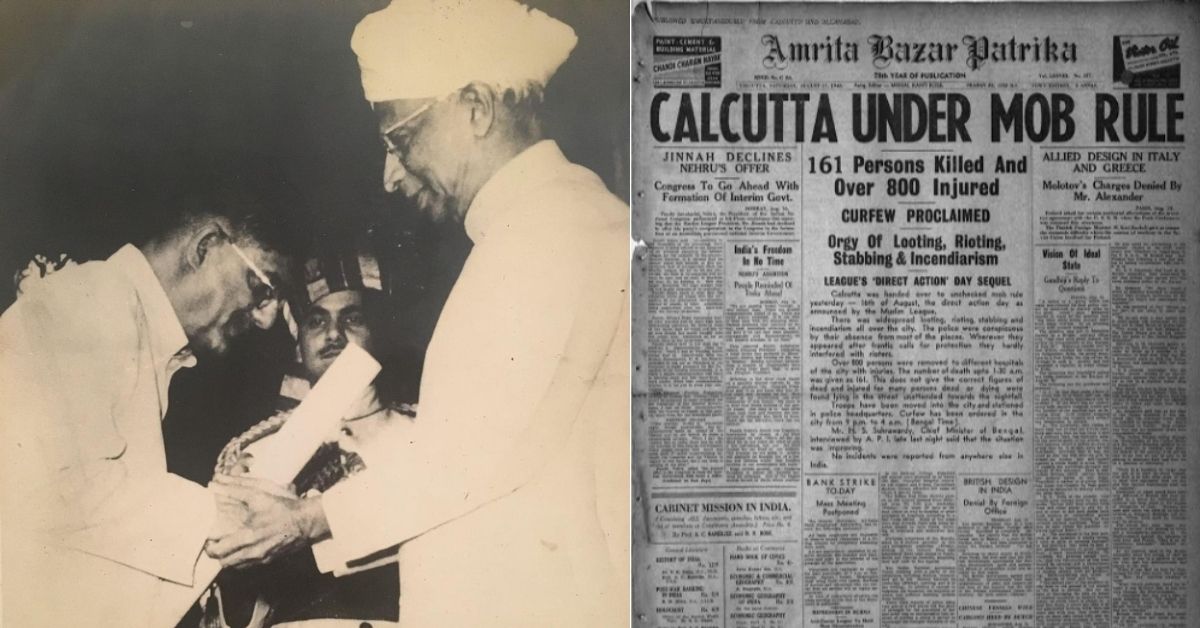

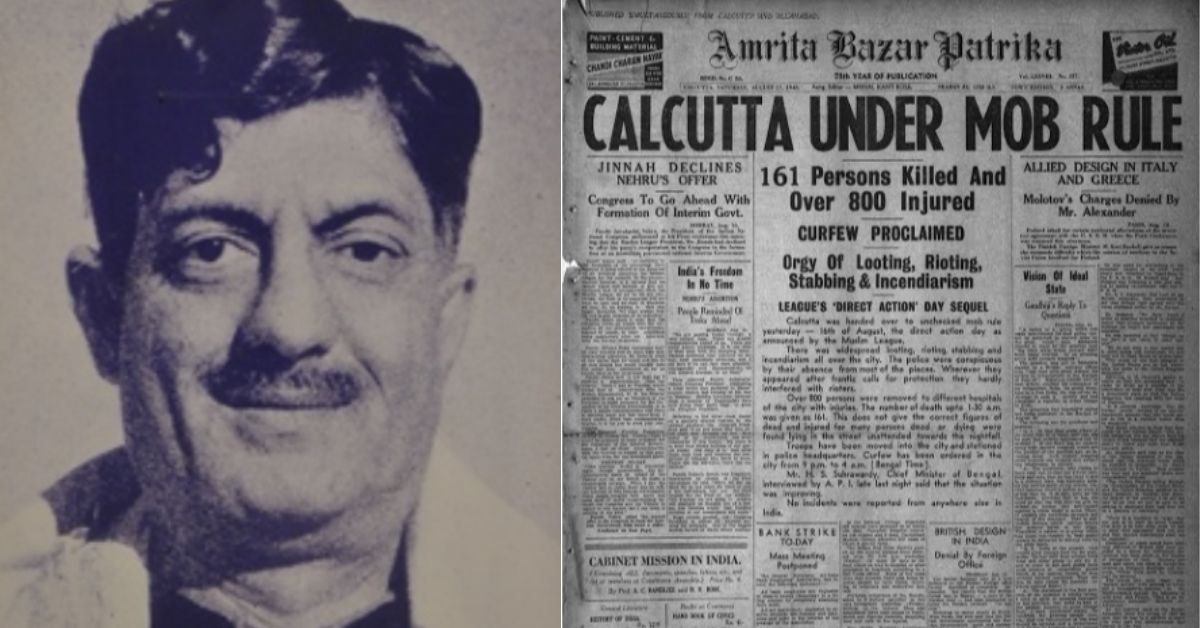

Under the editorship of the ‘grand old man of journalism’ Tushar Kanti Ghosh, the Amrita Bazar Patrika scaled great heights in India’s freedom struggle.

An arguably apocryphal anecdote about Tushar Kanti Ghosh, often regarded as the ‘grand old man of journalism’, goes like this:

In the 1940s, during a reception, Tushar was approached by the Governor of Bengal. This was a time when his newspaper, the Amrita Bazar Patrika, was known across the country for being a leading voice against the government. It had already surpassed the confines of Bengal to establish an important place in other parts of India and used to report in both Bengali as well as English. Its English reportage, it seems, was not up to the mark.

“Tusharbabu,” the Governor said, “I understand that many read your paper, but I must confess, it often does some violence to the English language.”

To this, Tushar is said to have replied, “That, Your Excellency, is my contribution to the freedom struggle.”

Years prior, when Tushar’s father Sisir Kumar Ghosh was the editor of the Patrika, Lord Lytton had passed the Vernacular Press Act (1878) to curtail press freedom and criticism of the government. “It was understood that the blow was aimed mainly at the Patrika,” wrote Srikanta Ray in Bengal Celebrities (1906).

Before the passage of the Act, Sisir Kumar was approached by diplomat Sir Ashley Eden, who offered government patronage in exchange for having the editorial content vetted before publishing.

The editor’s answer had been instantaneous no. “Your Honour,” he remarked, “there ought to be at least one honest journalist in the land.”

It was this incident that eventually led to the passage of the Act. The Patrika, which had been reporting in Bengali all this time, switched to bilingual reportage from its very next issue. In the history of Indian journalism, the paper is most famously recalled for this “overnight transformation”.

Through the course of its 123-year run, the Patrika saw — and survived — many attempts to quash press freedom.

For example, in 1919, the newspaper’s security deposit with the government had been forfeited due to two editorials that the paper had released — ‘To Whom Does India Belong?’, and ‘Arrest of Mr Gandhi: More Outrages’. In May the same year, General Michael O’Dwyer banned the paper’s publishing in the state of Punjab.

But for a newspaper whose very inception had been rooted in revolt and revolution, it would take a lot more than curbs and threats to even make a dent.

Shaping Indian journalism

In 1868, Sisir Kumar was one of the few rural reporters to report on the Indigo Revolt (1859), and the plight of peasant farmers being exploited by indigo planters. “Sisir Kumar soon found that if the people [were] to be properly served, it could only be done through the medium of a newspaper,” wrote Ray.

The paper began its journey in Magura (later renamed Amrita Bazar), a small village in Jessore district, located in what is now Bangladesh. Sisir later shifted the office to Calcutta in 1872.

During his reign as editor, he juggled many roles at once — of a manager, a printer, and a compositor all in one. He was a man unaffected by roadblocks. When Jessore faced a severe scarcity of paper, he travelled to Pandua to learn the art of papermaking. Under his leadership, the paper moved beyond the confines of Bengal to other parts of the country.

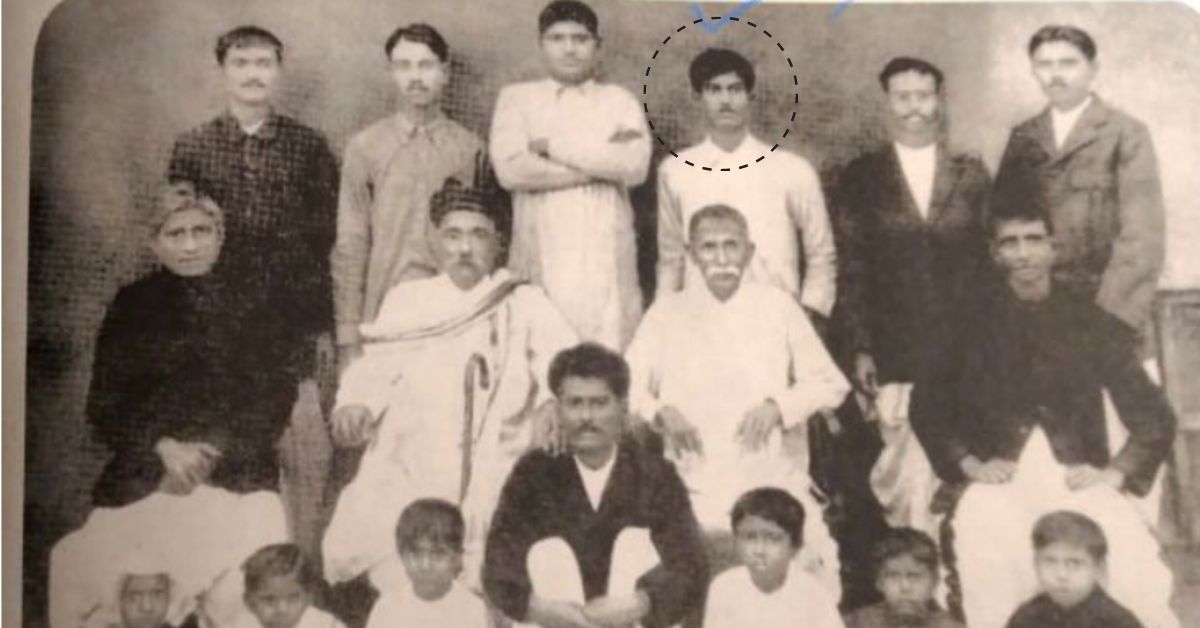

The Patrika was revered by many nationalist leaders. While Gandhi said it was “really amrit”, Bipin Chandra Pal credited it with being “the most outspoken” in its criticisms of public policies. The stories the Patrika published also resulted in the readmission of Subhas Chandra Bose and other students who had been expelled from Presidency College.

Sisir Kumar managed the paper until he died in 1911, after which it was taken over by his brother, Golaplal Ghosh. In 1928, Tushar took over the newspaper.

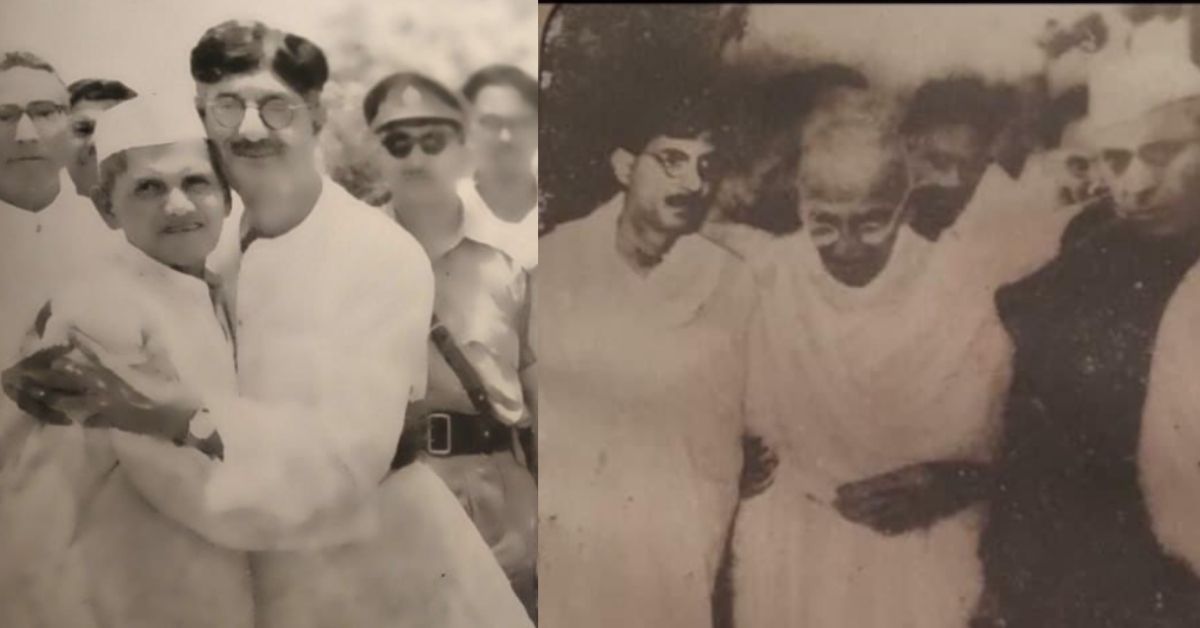

Under Tushar, the Patrika, one of India’s oldest newspapers, ran coverage for more than half a century. “As the editor of a nationalist newspaper, he had many responsibilities when he took over,” Tania Ghosh, Tushar’s great-granddaughter, tells The Better India. “He continued the legacy that my ancestors had paved the way for. He never gave into the government’s attempts to curb press freedom. For this, he was even jailed in 1935, when he reported on the working of the administration and judiciary.”

Tania says the articles were never “inflammatory”. “He was smart. He wrote his articles in a way that stung the British, but left them powerless to take any actual action,” she explains. “He could inspire people to join the freedom struggle while working within the ambit of the law.”

Citing one example, she recalls his reportage during the Bengal Famine of 1943. “He reported that while there were states that had a severe shortage of grains, there were some that had an excess. The Patrika questioned why there was a lack of equal distribution at the hands of the government. It was clear that the British were withholding this transfer of grains, because the Second World War was also going on at the time. They chose to store the grains for their troops, and not for the citizens.”

A hand written letter from Sarat Chandra, Netaji’s elder brother, to Tushar Kanti Ghosh. The address mentioned was the bose family’s residential address that’s now a museum in Kolkata. @IndiaHistorypic @MissionNetaji #family #History #Legacies pic.twitter.com/SSQgfT3XFW

— etap42 (@etap42) February 2, 2022

The paper minced no words when criticising the Partition of Bengal either. Of Lord Curzon, who presided over the division, the Patrika said he was “young and a little foppish, and without previous training but invested with unlimited powers”. Such editorials often thrust the paper in the crosshairs of the government, but there was no letting up.

Tania says that it was her great-grandfather’s vision to ensure that honest reportage would reach all corners of the country. “He wanted to reach the northern belt of India, for which he targeted Allahabad, which was also at the centre of the freedom struggle in those times,” Tania says. “Here, he started the Northern India Patrika and Amrit Prabhat.”

She adds that the Amrita Bazar Patrika was also the first to use chartered flights to distribute the paper across India. “This was unheard of in those times,” she notes.

In 1935, Tushar started the Bengali daily Jugantar. At the time, there was already a newspaper by the same name, being run by revolutionaries in Bengal. When most of its columnists and editors were jailed by the government, Tushar bought the name for Rs 500 from Sivaram Chakravorty, a humourist who had been struggling to keep the paper alive. Years later, Tushar entrusted the editorship back to Sivaram.

Writer Joy Bhattacharjya said that the Patrika also pioneered investigative journalism. “The Patrika once found a letter in the viceroy’s rubbish bin, which exposed a British plot to remove the Dogra kings of Kashmir from power. The resulting stories caused such an outcry that the British were forced to abandon the plan,” he noted.

Other investigative coverage of the paper included a study of the lack of Indian representation in the post master’s office.

As the Partition of India neared, communal riots spread rapidly and widely across the nation. On 16 August 1946, what is now referred to as Direct Action Day, largescale violence between the Hindu and Muslim communities broke out, leaving more than 4,000 people dead and over 1 lakh homeless. In light of the event — also regarded as the 1946 Calcutta Killings — and the advent of the Partition next year, the Patrika strongly advocated for communal harmony. It went three days without publishing a single editorial.

‘No divisive politics’

Tushar ran the paper for 60 years, till it was shut in 1991. Towards the 70s and 80s, the paper had started taking a slightly different direction. Journalist Manojit Mitra, who worked with the Patrika at the time, told The Print, “Bad management killed the newspaper. I was also not very happy with their editorial policies while I was working there. They didn’t have clear notions about what they wanted to do with the newspaper in sharp contrast to what the newspaper stood for during the freedom struggle. In the late 80s, it used to toe the line of the government of the day.”

Its circulation had fallen to 25,000 by then, and funds were too low to pay any of its employees. There was also strong competition from papers like The Statesman and The Telegraph. Tushar remained the group editor till his death in ‘94.

Despite the paper’s fall from glory, he remained respected and held in high regard. For his contributions to literature and the field of journalism, he was awarded the Padma Bhushan by the Government of India.

In recent years, there has been an attempt to digitise the Patrika for its extensive coverage of the nationalist movements in India, Partition of Bengal, Indian perspective on both World Wars, the famine of 1943, the independence of India, the Partition and influx of migration and related trauma, and the process of nation-building in the post-colonial period. The Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta took up the project of digitising the Patrika and Jugantar for safe storage and retrieval in 2010. Newspaper archives are also available at the Nehru Memorial Museum & Library, Delhi.

Today, Amrita Bazar Patrika is regarded as ‘fiery’ and ‘brave’. But Tania says there was simply a nuance to Tushar and the Patrika’s reportage, which was level-headed. “They didn’t need to shout and intimidate to prove their points. They were critical where it was needed. The paper never engaged in divisiveness,” she says.

Sources:

amritabazarpatrika.org

Jstor

Google books

Yumpu.com

Twitter

Hindu Frontline

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167