Padma Winning Doctor Couple’s Healthcare Model Has Been Replicated in 100+ Countries

Centred in Jamkhed village in Ahmednagar district, and extended to other villages in neighbouring districts, Dr Mabelle Arole and Dr Rajanikant Arole's Comprehensive Rural Health Project (CRHP) remains the gold standard of what it means to provide community-based primary healthcare to rural India.

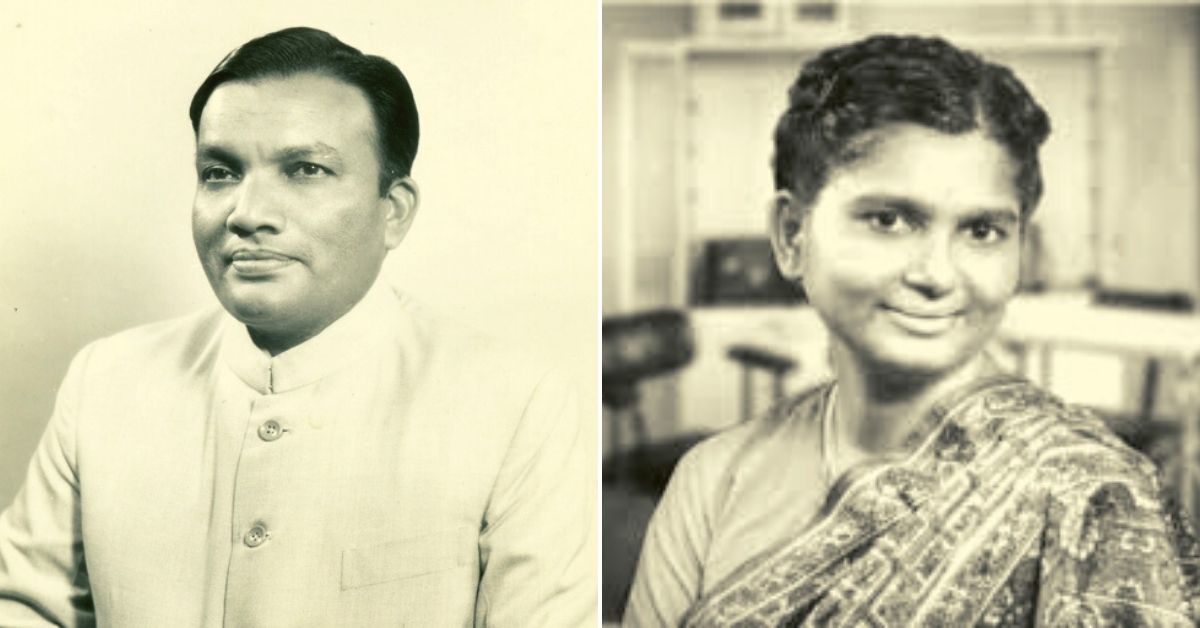

Last week, a remarkable thread on Twitter by Kiran Kumbhar, a physician and doctoral student at Harvard University, opened many eyes to the groundbreaking Comprehensive Rural Health Project (CRHP) in Maharashtra. It was first established by doctors and public health pioneers Dr Mabelle Arole (1935-1999) and her husband Dr Rajnikant Arole (1934-2011) in October 1970.

Centred in Jamkhed village in Ahmednagar district, and extended to other villages in neighbouring districts, the CRHP remains the gold standard of what it means to provide community-based primary healthcare and improve the general standard of living in rural India.

Recognised by the WHO and UNICEF, their model of public health has not only dramatically improved indicators like maternal mortality and infant mortality rate in these parts but also addressed issues of caste and gender inequality in attaining those targets. Spanning over five decades and beyond their lifetimes, the Aroles’ model has gone on to impact the lives of approximately 500,000 people in rural Maharashtra and has been replicated in more than 100 countries.

This model, according to Biraj Patnaik, executive director at the National Foundation For India, “was the precursor of later community health worker models including the Mitanin programme in Chhattisgarh that was the precursor of the ASHA programme we have nationwide” representing “unbroken chain of legacies of public health interventions, each building on the previous one.”

The CRHP model was also “instrumental in influencing the concepts and principles embedded in the 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata”, according to an academic paper by Henry Perry of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. This declaration, which the WHO adopted, identified primary healthcare as the key to the attainment of the goal of Health for All.

By all accounts, this is a remarkable success story that needs to be told more extensively.

Developing a Model

Rajanikant, who was better known to his peers as Raj, met Mabelle at the Christian Medical College in Vellore in 1954, where they studied medicine. The son of school teachers in Ahmednagar district, Raj’s interest in medicine came as a result of seeing two of his friends die of infectious diseases. Mabelle, meanwhile, was born into a family of scholars with a history of social service in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, and had family ties in Tamil Nadu.

Both young doctors shared aspirations of helping India’s poor and first worked in the rural areas of Maharashtra and Karnataka, where they identified the problem.

“After graduating from medical school my wife and I worked in a rural voluntary hospital in Maharashtra State during 1962-1966. This 70-bed hospital was the only facility available for the 100,000 people in the area. It offered traditional western curative medical care to those who found their way to its doorstep. After four years of service, we recognised that 70% of illnesses were preventable and large numbers of patients ‘cured’ in the hospital were going back to the same environment and later returning to the hospital for the same sort of episode of illness. This repetitive pattern of simple preventable illnesses could not be changed by the hospital even though it was situated in the heart of the rural area,” they wrote in a 1975 paper for WHO.

In the article, they went on to add, “Since a traditional curative-oriented hospital system does not penetrate the communities and does not see patients as a part of a community in relation to the environment they live in, it fails to meet the total needs of the community.”

Following their stint in the field, they left for the United States on a Fulbright scholarship where they undertook residencies and completed their masters’ degree in public health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, under the guidance of Carl Taylor, a pioneer in public health. It was here when they drew up their plan for providing medical care to rural India:

We had formulated the following criteria for establishing a viable and effective health care system. (l) Local communities should be motivated and involved in decision-making and must participate in the health programme so that ultimately they “own” the programme in their respective communities and villages. (2) The programme should be planned at the grassroots and develop a referral system to suit the local conditions. (3) Local resources such as buildings, manpower, and agriculture should be used to solve local health problems. (4) The community needs total health care and not fragmented care; promotional, preventive, and curative care need to be completely integrated, without undue emphasis on one particular aspect.

Upon their return to India, they embarked on their project. Funding for this project initially came from the Christian Medical Commission, which raised money through “religious and secular agencies”. With assistance from community leaders and local government officials, they began their work in Jamkhed out of a makeshift clinic. In the initial months, they were treating patients with chronic ailments like fever, diarrhoea and malnutrition, and performing surgical and obstetric emergencies, serving approximately 250 patients daily for free or a nominal amount.

This wasn’t what they wanted to achieve, i.e.“total health care to everyone in the area.” However, the reputation they had garnered for their clinical services offered them a “springboard for launching community health programmes” and getting the affected people invested in them.

Health For All

While treating these patients, they would visit a village and speak to village council members, community leaders and the people. “These intimate contacts soon made us realise that their priorities were not health but food and water,” the authors said.

They began with access to food, particularly for the most vulnerable which include children under five years of age and mothers. The local community began digging wells in the field, and farmers directly benefiting from the water donated a part of their land to grow food for these programmes. With assistance from donors, they even bought tractors for these farmers. For access to safe drinking water, they reached out to the community and local government officials, who organised a survey and donors paid for the construction of deep tube wells “with an average depth of 180 feet “fitted with hand pumps”.

Local volunteers were trained to oversee the pumps. With access to safe drinking water, the incidence of waterborne diseases was minimised. For the delivery of healthcare to the remotest villages, they established mobile health teams consisting of “a physician, nurse supervisor, social worker, auxiliary nurse midwife, driver, paramedical worker, and village health worker [VHW].”

Writing the preface to ‘Jamkhed: A Comprehensive Rural Health Project’ (1994) by Mabelle and Rajanikant Arole, Carl Taylor said, “They [Mabelle and Raj] went beyond simply improving health conditions…They demonstrated that health could be an entering wedge into total socioeconomic development. Many…had been talking about empowerment and conscientisation of people in greatest need, but the Aroles showed it was possible.”

VHWs, broadly known as community health workers (CHWs), were central to this spirit of empowerment. Since a significant part of their work in primary healthcare is concerned with women—maternal and child health and population control—it’s only natural that VHWs are “selected from middle-aged women who are interested in being of service to the community.”

“The village council recommends three or four women and a suitable woman is selected from among them. These women are active, well-motivated, respected members of the community. They are mostly illiterate and do not have household responsibilities. In-service training is provided for the village health worker (VHW),” note the Aroles in their WHO paper.

Adding to this description, Henry Perry and Jon Rohde note in their 2019 paper, “She [CHW] receives training in health, community development, communication, and personal development. At the outset, many of these CHWs were illiterate, drawn from the ‘untouchable’ (Dalit) castes. The primary responsibilities of the CHWs are to share their knowledge with everyone in the community [collect data], provide basic health care, organize groups, and offer special support to the poorest and marginalised members. Although the CHWs are volunteers, they are taught skills that help them earn their living through microenterprise.”

According to anthropologist Patricia Antoniello, who wrote about CRHP in a book titled For the Public Good: Women, Health, and Equity in Rural India, its long-term effectiveness comes from the power and dignity that it provides to its VHWs. “[The] women can transform their own lives. In one generation, they progressed from child brides and sequestered wives to valued teachers and community leaders. CRPH [helped them] demonstrate their strength, persistence, and resilience to overcome caste and gender inequality.”

In her book, she quotes a VHW Hirabai Salve, who reportedly said, “Before becoming a VHW, I never thought, who am I? I thought I was less than any animal. I did not know how to live. Because I am from a Harijan, a Dalit community, nobody respected me.” Going further, she wrote that the “most revolutionary idea of CRHP was to develop methods to directly challenge caste and gender inequality in communities.” In a fascinating anecdote, Antoniello refers to how the Aroles directly challenged these caste and gender hierarchies in their community outreach.

“Ushabai Bangar, one of the first generation of VHWs, remembers that Dr Mabelle used the breakfast clubs as a way to interrupt the pattern [of kids sitting together on caste lines]: ‘I saw what Dr Mabellebai was doing. She mixed up the seating of children in the circle. She put the girls with braids together. Then she sat girls with red hair ribbons together. And like that she mixed up the different [caste] groups’,” wrote Antoniello.

Similarly, a Dalit VHW told the author how Dr Raj, while accompanying a mobile health team to visit the house of sarpanch, took the “chipped and cracked cup and saucer” meant for her and drank from it.

The sarpanch wasn’t very happy about it. In other words, there was no way of exercising long-term change unless and until such inequalities and injustices continued.

It’s something the Aroles also mention in their 1975 WHO paper:

“The village health worker feels important because of the new role she plays in the village. Having once convinced herself of the various health needs she can bring about change much faster than a professional…Since her incentive is not money but job satisfaction her services are not expensive and are within the reach of the community.”

For example, the Aroles cite how often many young women reach out to them secretly for family planning advice since it was something their mothers-in-law wouldn’t approve of. Besides young mothers and children, they also regularly followed up on chronically ill patients with TB and leprosy and relay information about suspected cases to mobile health teams.

“Since 1970, almost 10,000 tuberculosis patients in Jamkhed have been identified and successfully treated, as have more than 5,000 patients with leprosy. Part of the treatment involved integrating these patients back into the life of their communities. A comparative study showed a much lower level of social stigma associated with leprosy in Jamkhed CRHP villages than in villages in other areas,” noted Perry and Rohde in their paper.

Measuring Impact

In 1970, according to Perry and Rohde, the “infant mortality rate was 176 per 1000 live births, 40% of children younger than five years were malnourished, and coverage rates for family planning, prenatal care, and birth attendance by a trained provider were all less than 1%.”

They go on to note: “Within five years, the infant mortality rate [in the area] fell to 52 per 1000 live births, antenatal care coverage increased to 80%, 74% of deliveries were conducted by trained personnel in hygienic conditions, the percentage of children who were fully immunised increased from 1% to 81%, and leprosy prevalence dropped by half.”

In 1990, the infant mortality rate dropped to 26 per 1000 live births, while 60% of eligible couples were using family planning. [Also] “fewer than 5% of children were malnourished, and the prevalence of tuberculosis had fallen by two thirds. Neonatal tetanus disappeared as a result of maternal immunizations and sterile umbilical cord care.”

As of 2019, 100% of pregnant women receive antenatal care and have safe deliveries, and fewer than 1% of children are malnourished. “According to statistics still maintained and scrutinised by communities in the area, the infant mortality rate is now 15 deaths per 1000 live births, and the maternal mortality ratio is less than 100 per 100,000 live births. These levels represent about half the mortality of similar populations in rural Maharashtra,” they add.

None of these results can be divorced from the efforts Aroles made to address caste and gender inequities, and other injustices afflicting rural life. Their legacy today is being carried forward by their children Dr Shobha Arole and Ravi Arole.

You can visit the CRHP website here.

SOURCES:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6459630/#bib5: The Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural Health Project and the Alma-Ata Vision of Primary Health Care by Henry B. Perry, MD, PhD, MPH and Jon Rohde, MD

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/40514: Health by the people/edited by Kenneth W. Newell (1975)

https://twitter.com/kikumbhar/status/1487644133787377664: Kiran Kumbhar/Twitter

https://www.amazon.in/Public-Good-Health-Equity-Practice/dp/0826500242: For the Public Good: Women, Health, and Equity in Rural India by Patricia Antoniello

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(11)61008-8/fulltext: Rajanikant Arole Obituary by Stephen Pinker

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167