From Son of Tonga Driver in British India to Business Icon in Africa: A Story of Grit

Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee was the entrepreneurial legend of Kenya. He rose from the oppressed class to become a business tycoon. This is his story.

Nairobi is known to have one of the most brutal traffic jams in the whole of Africa. Capital of Kenya and a business centre, like any other city, every morning is clouded with the cacophony of vehicles and crowds of people going about their day.

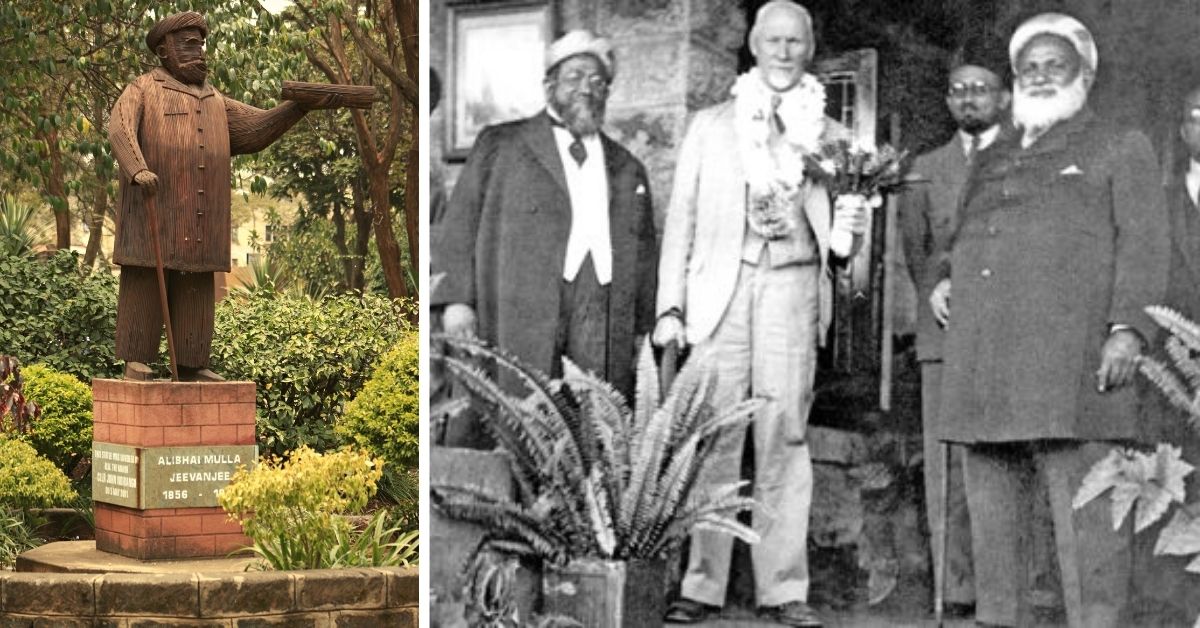

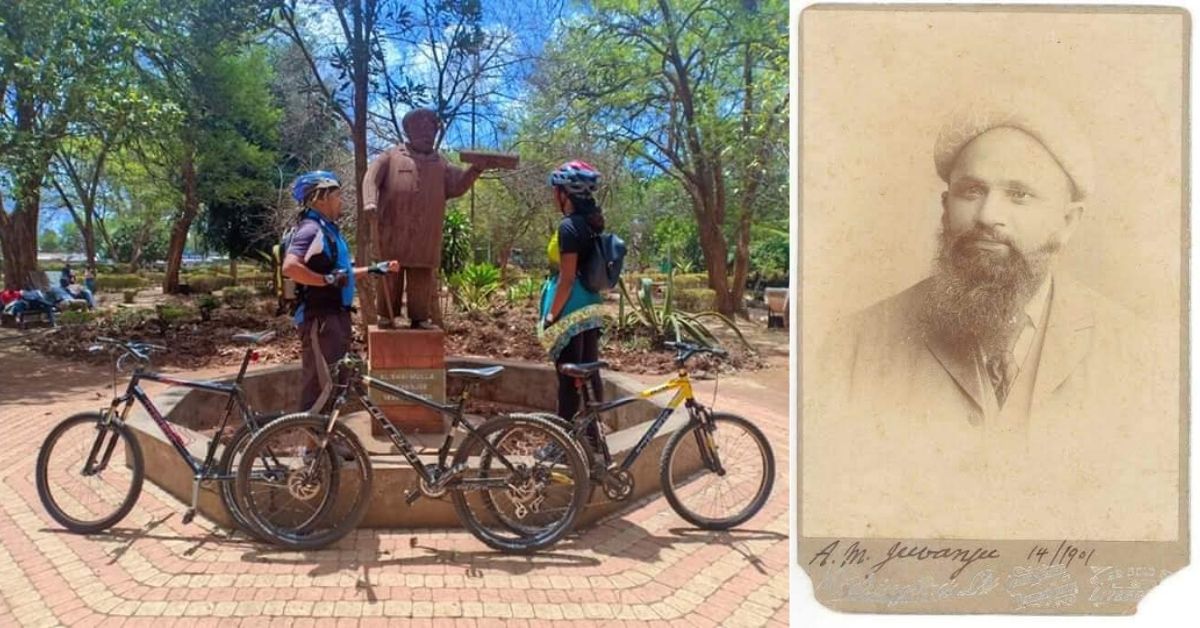

However, amid all the hubbub, a pocket of green haven, the Jeevanjee Gardens stands out like a much-needed space for respite. Enveloped with tall trees and multicoloured blooms, this 5-acre garden, at a glance, is not something exceptional. People lounging on the grass, having lunch, jogging or enjoying the greens, it’s all the usual that one would notice in any public garden or park. But it is the story behind it that is fascinating.

Although a relic of the past, made ordinary with time, a few steps into the garden would introduce you to the tall statue of an extraordinary personality, Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee. A foreigner who created a legacy of entrepreneurship and philanthropy in East Africa, this 116-year-old garden was made to immortalise his oeuvre.

An entrepreneurial legend

A Dawoodi Bohra who migrated from British India to try his luck in business, Jeevanjee turned out to be one of the most pivotal entrepreneurs and success stories in the British Empire.

Son of a tonga driver, he was born in 1856, in Karachi. Financial limitations and the Bohra community’s resistance towards Western education restricted Jeevanjee from receiving a formal education. According to late scholar and poet Saiffuddin Insaf from Bohra Reform Movement, the Bohra clergy had always been motivated to oppose western education and modern sciences, which contributed to restricting the community and creating ‘a narrow intellectual base’.

Jeevanjee, however, never agreed to this fate. His dreams were too big to fit into the constraints of the community and so at the age of 20, he decided to leave home and carve his path. He decided to embrace a nomadic lifestyle, travelling and peddling trade opportunities from one place to another. Every experience, good and bad, helped him learn an important lesson and contributed to polishing the fine business acumen he naturally possessed.

Seeking new experiences, opportunities and adventures, he eventually moved to the eastern coast of Australia. Here, he set up a company that would sell products from India. It was in Australia where he learnt to speak fluent English.

After some time trying to survive in the Australian market, he eventually moved back to Karachi in the 1880s and started another company that aided foreign ships. A decade later, Jeevanjee set sail to East Africa in search of newer trade opportunities.

At the time a substantial part of East Africa was under the occupation of the British Imperial East Africa Company. In 1895 the Crown took over the territory of modern-day Kenya and named it the East Africa Protectorate. This transition experienced in Zanzibar and Uganda as well made way for the construction of the Uganda Railway, a meter gauge line that was supposed to connect the interior parts of Uganda with the coastal city of Mombasa, on the Indian ocean. This development promised new opportunities for traders, luring many prospective entrepreneurs to the shores of Africa, Jeevanjee being one of them.

The next few years passed with Jeevanjee struggling to make his mark. Finally, in 1895, his luck took a turn when he managed to get a contract to supply labour for the Uganda Railway construction. From transporting 350 workers from Punjab, his business rose to success in just six years with him employing over 32,000 workers from India. Interestingly, the 1996 American film, The Ghost and the Darkness is set on the premise of this construction project which majorly had African and Indian construction workers.

Much to the distress of British immigrants, this Indian Bohra immigrant in the next two decades managed to earn massive success. This led him to expand into the construction business as well, whereby his company built several early government buildings and railway stations in Kenya.

In an article published in the Daily Nation, Kenya, Zarina Patel, Jeevanjee’s granddaughter and biographer adds that tracing back the history of the earliest construction buildings in Nairobi often lead to Jeevanjee, either as the investor, contractor or owner. In a way, Jeevanjee was one of the most prominent individuals who led to the foundation of the modern-day city of Nairobi.

Becoming more than a businessman

According to his granddaughter, Jeevanjee believed growth was only possible through diversification and evolution. A progressive individual, he would welcome original business propositions and open his mind, expanding in sectors beyond the construction sector, as mentioned in his 2002 biography titled Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee.

Owing to this, he started ventures in agricultural and industrial products as well as invested in consumer goods factories that produce ice and soda. In 1902, he even went ahead to inspire the masses through the power of media by starting the first non-European-led newspaper in East Africa called The African Standard. Jeevanjee continued to run it for three consecutive years before selling it in 1905. Today it is one of the largest circulating news daily with a 48 per cent market share in Kenya and 74,000 circulations.

Despite his massive contribution to society and financial success, Jeevanjee continued to suffer from racial injustice and discrimination from British settlers in Kenya. He was never to be treated equally despite all his achievements and was even barred from residing in some of the better-developed areas of the city, even though it was his construction company that had developed those areas in the first place. By the time he was appointed as a representative of Indians in the Legislative Council, he had decided to use his power to create change and not be just another financially well-off conservative puppet occupying the office to maintain the colonial status quo.

Striking the cords of much-needed rebellion against the racist policies, he established the East African Indian National Congress in 1914. Aimed at highlighting the interests of Indian residents, the party strived for equality between Indians and Europeans in Kenya. One of the prominent demands was to allow Indians to set up agricultural farms in the central Kenyan highlands, an area which was named the White Highlands and was restricted to only European settlements.

This, however, never could materialise, owing to the possibility that it would perpetuate the colonisation of African land, this time by Indians, something that several Indian nationalists were starkly opposed to.

However, this did not allow his work to dim. He redeemed himself by becoming one of the prominent members behind the negotiations for the British authorities to release the Devonshire Declaration, as mentioned in his biography. According to this declaration, the interests of Africans should be prioritised in case of any conflict of interest between native Africans and British, Indian or Arab settlers.

Dust to dust is not the end

Today, if one had to evaluate his net worth, it would be more than four million euros. However, by the end of his journey around the 1930s, a few wrong turns in business led him to bankruptcy. He passed away due to a heart attack in 1936 at the age of 80.

However, his work and impact continue to echo in the lives of modern-day Kenyans, especially those living in Nairobi. In a growing city that is constantly developing and evolving, several attempts to transform the Jeevanjee Gardens into a car park or shopping mall have been made. But the Jeevanjee Gardens is more than a time capsule to the people of Nairobi.

A heritage site and a symbolic remembrance of a time when the change had begun, it immortalises all that Jeevanjee has done for Indians settled in East Africa, as well as native Africans. And so, despite the political and corporate pressures seeking to uproot over a century old green sanctum, Nairobians continue to resist and keep this memory terrarium of hope and progress alive and breathing.

Featured story source (L-R): Facebook; Twitter

Edited by Yoshita Rao

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.