Rickshaw Puller Turns Innovator; Builds Devices That Earn Lakhs & Helps Uplift 1000s

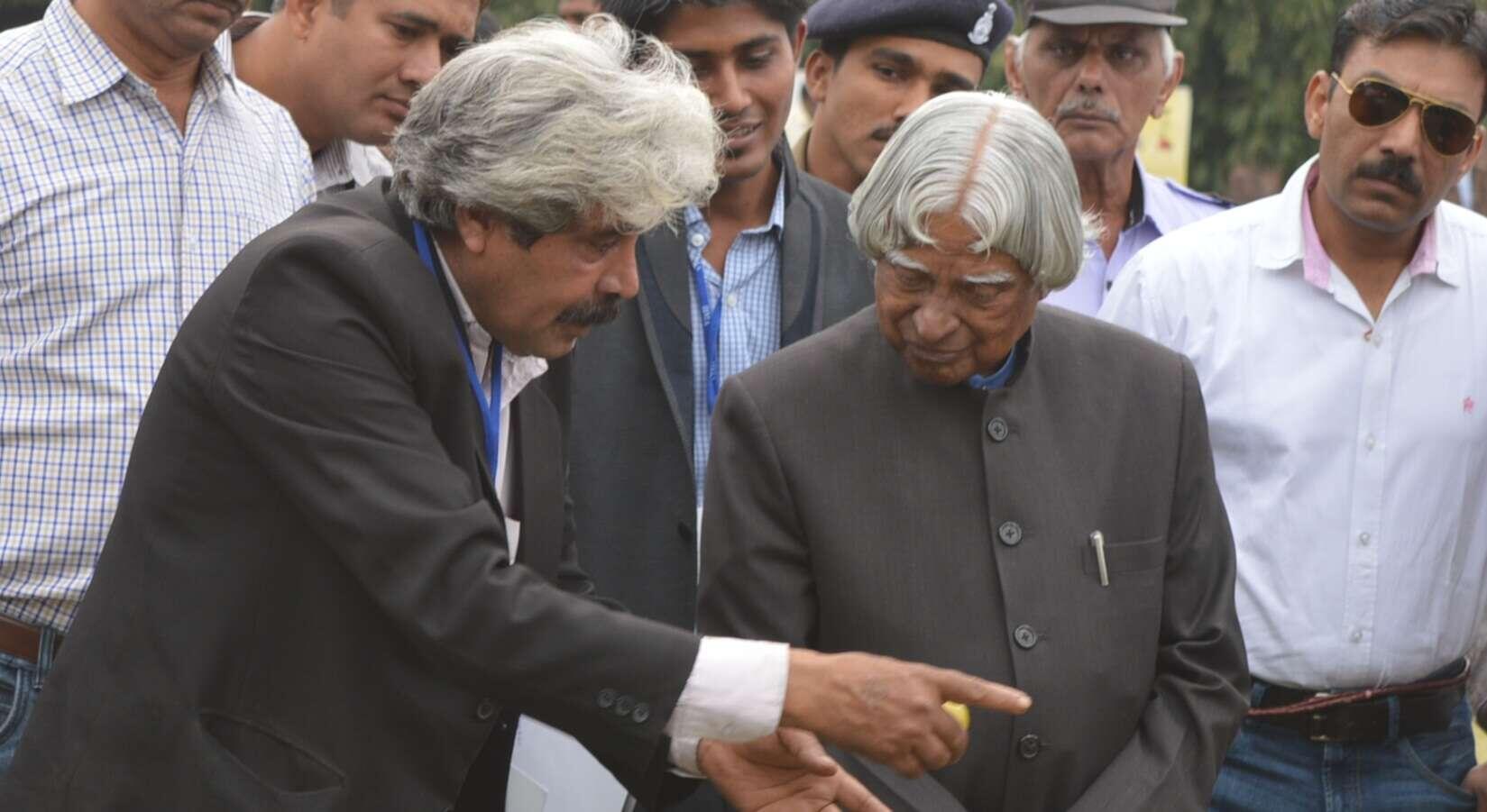

Dharambir Kamboj was a cycle rickshaw puller working on the streets of Delhi. Today the 58-year-old from Damla village in Yamunanagar district, Haryana, is a farmer, rural innovator and entrepreneur. In 2013, he even received a National Award from the President of India.

Dharambir Kamboj, popularly known as ‘Kissan Dharambir’, is the quintessential Indian success story. From a cycle rickshaw puller working on the streets of Delhi, the 58-year-old from Damla village in Yamunanagar district, Haryana, has gone on to become a farmer, rural innovator and entrepreneur.

In 2013, he even received a National Award from the President of India.

From sweating and freezing it out on the streets of Delhi to pay the Rs 6 per day rent to operate a cycle rickshaw, he today earns Rs 15-20 Lakh per annum from the sale of his patented portable multipurpose food processing (MPP) machine. The MPP machine processes a large variety of fruits, herbs and vegetables. Going further, he also earns an additional Rs 8 lakh (per annum) from the sale of processed products sourced from the produce grown on his two-acre farm.

The MPP machine also forms the backbone of his efforts to help fellow farmers and rural micro-entrepreneurs earn better profits, improve incomes and find employment. So far, his enterprise, Dharambir Food Processing Private Limited, has organised training programmes and workshops for more than 7,000 people across the country, including more than 4,000 women, besides supplying MPP machines to countries like the United States, Italy, Nepal, Australia, Kenya, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Uganda, etc.

Along the way, Dharambir has gone on to win other accolades like the State Award by National Innovation Foundation and Indian Council for Agricultural Research’s ‘Farmer Scientist Award’.

“By supporting social enterprises working in this sector to scale and succeed, what Powering Livelihoods, a Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW)-Villgro initiative, also tries to achieve is to motivate grassroots innovators to embrace entrepreneurship fearlessly. Dharambir Food Processing is a role model enterprise on that front, and the struggle of the entrepreneur is motivating beyond words,” shares Ananth Aravamudan, the Sector Head overseeing Climate Action projects at Villgro, an incubator of social enterprises, speaking to The Better India.

Here’s the story of how this remarkable Indian made it this far in life.

Humble Origins

Dharmbir, the son of humble farmers who also ran a small flour mill and made jaggery blocks out of sugarcane, was always a keen innovator. By the time he was five, he had already learnt how to operate a flour mill from his uncles. Then, in Class 8, he made an emergency lighting device using battery cells and diodes with assistance from his science teacher.

But after his matriculation, he had to give up formal education because his mother and sister fell seriously ill. His mother passed away soon after.

But his sister recovered, and following this, Dharambir got married, and in December 1985, his daughter was born. With a family to support, he left Damla for better economic opportunities and found his way to Delhi barely days after the birth of his daughter.

“Arriving in Delhi on a freezing winter night, I slept at the bus stand. By the next morning, I only had Rs 10 left in my pocket. With no money to go back home, I spent the day looking for work. Struggling to find any, I soon found a garage owned by a fellow Kamboj (a caste community). Upon seeing my matriculation certificate, he decided to rent out a cycle rickshaw for Rs 6 per day if I rode during the day. Unfortunately, life as a cycle rickshaw puller in Delhi was nothing short of hell. Sleeping on the footpath, getting bitten by mosquitoes, living in fear of getting run over by some vehicle, having no proper sanitation facilities, and the people showing no respect for the profession made me realise that this gig was just not worth it. Whenever people back home asked me about work during my visits to drop off some money home, I would tell them that I worked at a telephone exchange out of shame,” recalls Dharambir.

But in the year he spent in Delhi as a cycle rickshaw puller, Dharambir found solace in a public library near the Old Delhi railway station and the roadside stalls selling second-hand books. During his free time, he would read up on farming-related subjects like growing different types of exotic crops like broccoli, asparagus, lettuce, bell peppers, etc.

Ferrying customers to Khan Market, he would see shops selling imported asparagus for Rs 400 kg and 200 gm bottles of ‘Made in Peru’ guava jam sold for Rs 250.

Meanwhile, in the Azadpur Mandi, he saw large hybrid tomatoes sold for prices higher than their standard ones grown back home. And then there was the Khari Baoli street where farmers and vendors would sell flowers, medicinal and aromatic herbs for a premium.

In other words, the year he spent in Delhi, Dharambir did his research and tracked down information like where he could source seeds. However, the straw that finally broke the camel’s back was a severe accident that left him in a hospital and destroyed his rickshaw.

“This way of life wasn’t worth it to me, and the risks involved were too high for minimal reward. But seeing retailers in Connaught Place, Khan Market and INA, supplying imported mushrooms, asparagus, avocados, strawberries and baby corn among others to five-star hotels, and the high prices farmers were fetching at Khari Baoli for herbs planted a seed in my head. So, after the accident in late 1986, I decided to come back home and get back into farming again,” he says.

With seeds sourced from Delhi, Dharambir began growing hybrid tomatoes, followed by Okra (ladies’ fingers) and mushrooms. In the early days, he deployed chemical fertilisers, pesticides and insecticides as well. To ease the process of doing so, he built a lightweight spray machine instead of the heavier tanks that farmers carried on their backs.

His innovation soon caught the attention of a local district agricultural officer, who suggested that he should focus more on growing mushrooms since it offered significant margins. To improve his technique, the officer suggested visiting agricultural scientists at the Dr Yashwant Singh Parmar University of Horticulture & Forestry in Nauni, Himachal Pradesh.

In 1992, he made his way there. Besides picking up more efficient techniques on growing mushroom farming at the varsity and working on the land of farmers nearby who grew it, he also picked up valuable lessons in herbal agriculture and food processing.

This would prove extremely valuable a few years later.

Implementing the lessons he learnt there over three months, he returned home and extensively got into mushroom farming. By 1994, however, he realised that the chemicals used in his field had a devastating impact on the local wildlife. Dead birds, snakes, mice and other insects were appearing in and around his farm. Afflicted by the guilt of seeing many of these animals dying, he transitioned to herbal farming. He began adopting more organic techniques to grow crops and dramatically reduced his use of chemicals.

“When I started herbal farming in 1994, on one acre, I grew about 70 to 80 varieties of herbs with seeds from the varsity in Nauni and Pansari shops in places like Haldwani and Nainital. But the real turning point in my life came in 2004 when I went on a farmers’ tour to Ajmer and Pushkar sponsored by the Horticultural Department of Haryana,” he recalls.

Innovator Extraordinaire

During this visit, he interacted with farmers to learn about the Aloe Vera crop and its extracts for obtaining medicinal value products. After returning to his village, Dharambir was looking for ways to market Aloe Vera gel and other processed products as a lucrative venture.

In 2002, he met a bank manager who educated him about the machinery required for processing food products but quoted Rs 5 Lakh for the machine. This price was too steep for a farmer like him. Inspired by his wife, he began coming with ideas to build his own machine. Over eight months, Dharambir was ready with his Multipurpose Food Processing (MPP) Machine prototype. So, what’s the machine all about?

It is a portable machine, which works on a single-phase motor and is useful in processing various fruits, herbs and seeds. It also works like a big pressure cooker with temperature control and an auto cut-off facility. Further, it offers a condensation mechanism, wherein the extraction of essence and oils from a plethora of flowers, seeds and medicinal plants is made possible easily and quickly. It is a first-of-its-kind machine which can perform pulverising, mixing, steaming, pressure-cooking and juice/ oil/ gel extracting – all of these functions alone.

But how does this machine work? The device has an electric motor to drive the central shaft, and gauges for monitoring the temperature and pressure are provided so that they can be controlled for seamless processing of certain products. The machine is also equipped with an oil jacket outside the main chamber to prevent direct heating of the herbs.

Its portability makes it the most suitable for farm processing, thereby producing fresh farm products and reducing issues associated with transportation and stocking.

“The machine is designed as a cylindrical container made with food-grade stainless steel, and having an opening (with lid) at the top to feed the herbs and an outlet at the bottom to collect the residues (after processing). It can process a wide variety of products without breaking the seeds of the fruit or vegetable. This machine can be used for processing aloe vera (to make juice, hair gel, face wash, shampoo, hand wash, etc.), mango (to make chutney, jam), Amla (juice, powder, hair oil, laddoos, etc.), Tulsi, Ashwagandha and many other medicinal herbs, flowers like rose, Chameli, lavender, among others,” notes this description in a National Innovation Foundation document.

It is very simple to operate and can be operated by anyone with a few hours of training. Over the years, the size(s) and configurations of the machine have evolved. Today, the MPP machine is available in more than ten variants, with their processing capacities (volumes) ranging between as low as 12 litres and going upto 130 litres. In addition, the MPP machine can process over 100 varieties of fruits and herbs and has been patented.

“To extract aloe vera juice, gel and rose water, I first employed about 25 women and began supplying it to local pharmacies in Haridwar. We manufacture about 120 machines in a year and sell them for anywhere between Rs 55,000 to Rs 1.90 Lakh depending on the configuration. Considering all the costs, we make about Rs 15 to 20 Lakh annually from selling these machines, although we sell equipment worth over Rs 1 Crore. The smaller machines process about 40 kgs of produce in an hour, while the bigger machines process about 200 kgs an hour. Attached to solar power, the rate of production increases. We also conduct training programs for farmers, school students, and foreigners on how to use MPPs,” explains Dharambir.

Even today, he continues to farm, growing garlic, tulsi, aloe vera, among other crops. However, it has been 12 years since he sold his produce in the mandi. Instead, whatever is grown, he performs his value addition on the farm and then sells processed items to various buyers.

“My objective is to employ 250-300 women from my village in the food processing business. Our workshop is expanding, and we would like to acquire more space for our processing work. I grow and process on my farm aloe vera juice, tulsi water, tulsi tea, aloe vera gel, shampoo, etc. I earn about Rs 7-8 Lakh per annum. For the younger generation, which includes children of farmers in our village, we help and assist with any ideas. After all, they’re our future,” he says.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.