Nehru To Bose: Inside The Debating Society That Gave India Her Freedom Fighters

Founded in 1891, the Cambridge Majlis offered students from the Indian subcontinent a forum for debates, dialogue and cultural events, even though the British Raj had hoped otherwise.

The British Empire saw Cambridge University as a space where they could make “good boys and potential pillars of British rule in India”. The university offered admission to students from India who were often children of kings, civil servants, businessmen and barristers. These were meant to become the “brown sahibs” who would do the bidding of their colonial masters in various capacities.

However, like any academic institution of excellence, Cambridge also offered fertile ground for the open exchange and development of ideas. One such fertile ground was the Cambridge Majlis. founded in 1891.

(Image of Indian and British students posing for the camera at Downing courtesy Downing College Archives/Varsity)

This prestigious society gave students from the Indian subcontinent a forum for debates, dialogue and cultural events that fostered a stronger relationship between them, South Asians in the city, and the prestigious varsity. In the early days, the Majlis met at the home of Dr Upendra Krishna Dutt, an influential member of the Indian diaspora in the UK.

‘Majlis’ comes from the Persian word for ‘assembly’, and it was established as a social club, debating society and a platform where students from the subcontinent could engage in some level of activism. The Cambridge Majlis held no formal affiliation to the varsity.

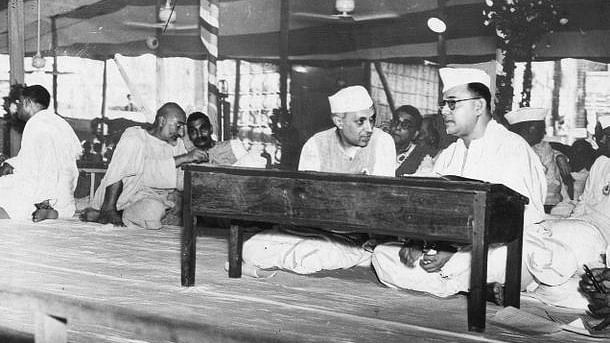

Although the colonial regime hoped that the varsity would produce loyal servants to the British ground, societies like the Cambridge Majlis instead ended up producing strong advocates against their rule including the likes Jawaharlal Nehru (Trinity College), Subhash Chandra Bose (Fitzwilliam College), Aurobindo Ghose (King’s College), Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew (Peterhouse), Syed Mahmud, Gurusaday Dutt (Emmanuel College), Dr Shankar Dayal Sharma (Fitzwilliam College), Mohan Kumaramangalam, Fazl-i-Hussain and KL Gauba, among others.

The Cambridge Majlis also hosted some of the most significant leaders, writers and intellectuals of the time — from economist John Maynard Keynes to writer EM Forster, priest CF Andrews, MK Gandhi, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Sarojini Naidu, Lala Lajpat Rai and Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

“This was the place where many of these future revolutionaries first met and brewed the potion of revolution that swept the subcontinent in less than half a century,” notes this article in Varsity, the Cambridge University’s independent student newspaper.

In fact, one of the first major political acts by student members of the Cambridge Majlis came after Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, instituted the Partition of Bengal, which separated the region into two separate administrative areas—Muslim majority East Bengal and Hindu majority Wast Bengal and Assam. Not only did this decision spark the Swadeshi Movement, an inflection point in the freedom struggle to come, it also sowed the seeds of Partition decades later.

According to the Varsity, “This 1905 partition also sparked the Swadeshi movement among the Cambridge students before it became a more widespread movement of boycotting British rule.”

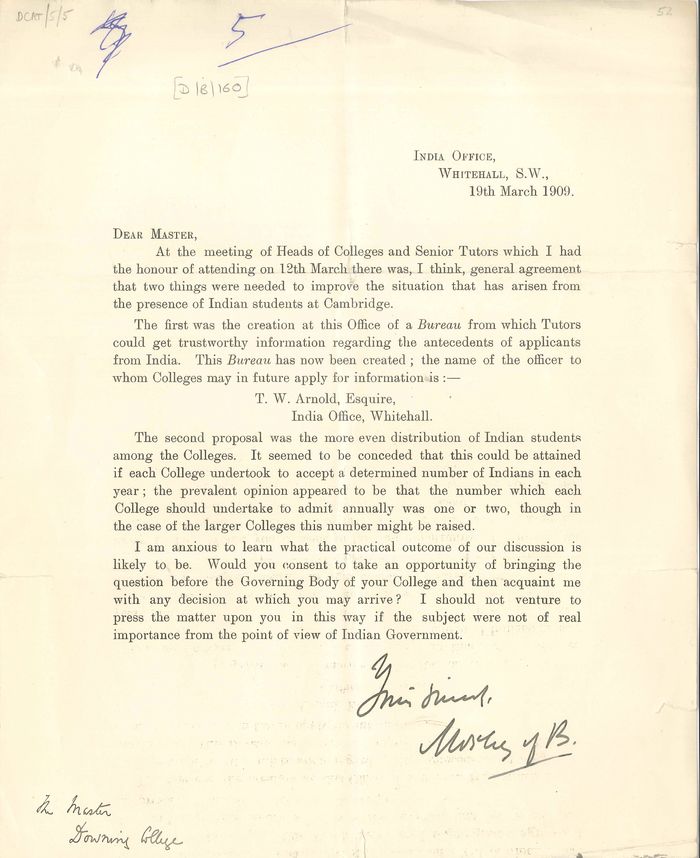

Matters only began to escalate from there, and while the varsity had less than 100 Indian students by March 1909, it became a serious concern for the British.

In March 1909, then Secretary of State for India Lord Morley wrote a letter to the Master of Downing College, Cambridge, raising an alarm about the rising number of Indian students there. “I should not venture to press the matter upon you in this way if the subject were not of real importance from the point of view of [the] Indian Government,” read the letter.

Three weeks prior to writing this letter, he warned the House of Lords of how “the extremists, who nurse fanatic beliefs that they will someday drive us out of India,” and was keen on rooting this “problem” from British universities. He wasn’t too off the mark.

As this article notes, “Many would leave as revolutionaries, ‘trouble-makers’ and independence advocates; even if their actions at University pale in comparison to the sedition and activism in India in the 30s and 40s, it was here [Cambridge] that this elite group, previously spread across the subcontinent, first met.”

Who Were These Students?

There is no doubt that a vast majority of students who attended Cambridge University at the time came from the upper echelons of Indian society. They came from families who had ties to the British Raj or intrinsically benefitted from their relationship with it. In fact, the likes of Nehru studied in elite English schools like Harrow before his time in Trinity College, Cambridge.

In other words, these were students cocooned away from the extreme challenges the common man in India faced during the British Raj.

Nonetheless, they made an active choice of understanding the perils of British rule in India and challenging it through debate and discussion. The seeds of their activism for Independence were sown (in some part) in the Cambridge Majlis. But it’s imperative to note that the platform not only discussed the concerns of students about the British Raj, but also spoke on other subjects of relevance and interest to them.

One such student was Jatindra Mohan Sengupta, who came from a prominent Zamindar family in Chittagong district, and whose father was a member of the British Legislative Council. Jatin, who was two years senior to Nehru, became the President of the Cambridge Majlis in 1908. During his tenure as President, he urgently pressed for discussions about Britain’s control of India. Following his time at Cambridge, he would get called to the Bar at Grays’ Inn.

Despite starting a successful practice in Calcutta (Kolkata), Jatin would give it up and join the freedom struggle in 1921 as an integral member of MK Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement, overseeing matters in Bengal. Joining Jatin in this new direction was his wife and British-born Edith Ellen Gray, later known as Nellie Sengupta, whom he had met in Cambridge.

He would go on to play important roles in the freedom struggle, organising worker strikes, defying the ban on various freedoms for protestors, defending revolutionaries like Surya Sen in court and attending the Second Round Table Conference in 1931, where he supported the Indian National Congress and submitted photo evidence of police brutality during the quelling of the Chittagong Rebellion. He passed away two years later while locked up in Ranchi, while Nellie would go on to play a key role in the freedom struggle and social work post-Independence.

Following Independence, the society continued to meet with students now from different countries in the subcontinent and even survived two wars between India and Pakistan (1947 and 1965), but things came to a head during the 1971 War of Liberation. The Cambridge Majlis fell into a steep decline before it was revived once again in March 2019.

Whether we know it or not, this society opened the doors for many of our important freedom fighters.

(Edited by Divya Sethu)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167