How Books & A Royal Mistress Shaped An Indian Slave’s Role In The French Revolution

Louis-Benoit Zamor was taken by British slave traders from his birthplace in Bengal and sold to Louis XV, who in turn 'gifted' him to his mistress, Madame du Barry. However, two decades later, Zamor became a participant of the French Revolution. Here's his incredible story.

This story has all the makings of a war drama — a king, a mistress, a slave, a revolution, loyalty, and ultimately, betrayal. But, at its centre is a young Indian boy, taken from his birthplace when he was all but 11 years old, never expecting a future role in one of the most significant events of European history — the French Revolution.

The aforementioned mistress was Jeanne Bécu, Comtesse du Barry, or Madame du Barry, who was ‘gifted’ a young slave by King Louis XV of France. This boy was to be her page, but the countess developed a strong liking for him instead and educated him. This education would inspire ideals in him that would ultimately lead to the countess’ doom. But before we get to that, who was this young boy?

‘The object of my regard.’

In France, Zamor was baptised and christened as ‘Louis-Benoit’. But his birthplace lay halfway across the world in Chittagong, Bengal (now in Bangladesh). It is speculated that he may have been of Siddhi origin.

He later told people he was born in the Bengal Sabah of the Mughal Empire and that when he was around 11 years old, he was kidnapped by British slave traders and taken to Europe.

Eventually, Zamor was taken to France via Madagascar and sold to King Louis XV as a ‘slave’. The king handed him over to Madame du Barry, a royal mistress at the time – probably around 1769.

The countess’s own story is nothing short of a period film — she was the illegitimate daughter of a French seamstress and a friar, who rose through the ranks with her beauty and caught the king’s attention. She was famed for her golden locks, bright blue eyes and snow-white skin.

Before she found herself living a lavish life on the floor right above the king’s quarters in the magnificent Palace of Versailles, she was a poor woman who struggled to make ends meet – and was the lover of many rich men (including the king’s courtiers). Regardless, her fortunes changed around the age of 25, when the king (who was around 58) took a fancy to her.

As for Zamor, she seems to have taken him up as a pet project. Jeanne dressed Zamor up in elegant clothing, kept him by her side at all times, and showed him off, the way one would a pet.

In her memoir, she wrote that her first love and priority was Dorine, her dog, who “sipped her coffee daily from a golden saucer, and Zamor (who seems to have disliked Dorine) was appointed her cupbearer”.

Zamor was the “second object of [her] regard”. She called him a ‘young African boy’. Madame du Barry believed all her life that he was African, but this was nothing abnormal at the time. The true origins of persons of colour were not of importance in the mid-to-late-18th century French.

Zamor was said to be “full of intelligence and mischief” and “independent in his nature, yet wild as his country” (she was entirely wrong about which country that was, though).

This is not to say that their relationship was positive— Zamor was viewed as a “young urchin” who performed “monkey feats” that she often looked upon as a source of her amusement.

The racism Zamor was subject to was not just benevolent. In the courts, he was often humiliated and ridiculed and raised as more or less a toy or “plaything” for the countess. So he found solace in his thirst for knowledge and turned to texts written by philosophers, particularly those by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. But, at some point, Zamor also began to detest the countess and her lavish lifestyle.

In her memoir, Madame du Barry had written that Zamor considered himself an equal of whoever he met, so much so that he rarely acknowledged that even the king himself was his superior. This simple description proved to be a foreshadowing of sorts. A quiet storm brewed in Zamor’s mind – a feeling of indignation that he kept to himself.

By 1789, Zamor was a grown man, and the fortunes of Jeanne had changed quite a bit. King Louis XV died in 1774, and Madame du Barry was promptly shipped off to a convent. She eventually purchased an estate and lived a quiet life there, having the occasional affair with other noblemen. Zamor remained in her service.

The rule of King Louis XVI was ongoing, and Marie Antoinette was all the rage. And the French Revolution was around the corner.

By then, Zamor, alongside another member of the Madame’s staff, joined the Société des Jacobins, amis de la liberté et de l’égalité, or, Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality. Zamor was eventually inducted into the Committee of Public Safety and later, the Revolutionary Surveillance Committee.

The Jacobins helmed the infamous ‘Reign of Terror’, alongside launching stringent measures like price control and food seizures.

‘…Born in Bengal, India’

Several affluent people in France (who were most likely to lose their heads should the worst happen) fled to other countries when the revolution began, with many settling in Great Britain. They were known as the émigrés and were declared enemies of the revolution.

Perhaps England was the eventual plan of Madame du Barry as well, who began visiting England frequently under the pretext of retrieving lost jewellery. Zamor warned her about this alliance with the aristocrats (she could have rightfully claimed to have no noble blood at all). But the page’s warnings fell on deaf ears.

He was, in any case, plotting to have her arrested, which he managed to do for a short while. She discovered who her denouncer was and had Zamor promptly fired from her service when she got out.

Zamor decided to take things to the next level. During her return from one particular trip to England, Zamor had Madame du Barry arrested on suspicion of financially assisting the émigrés.

He testified against her in the revolutionary tribunal. At the trial, he signed his birthplace as Chittagong — “Louis-Benoit Zamor, né au Bengale, dans l’Inde…[Louis-Benoit Zamor, born in Bengal, in India…]”

His role in her arrest led to her being condemned to death. The countess attempted to save herself by revealing the location of jewels she had hidden, but in vain.

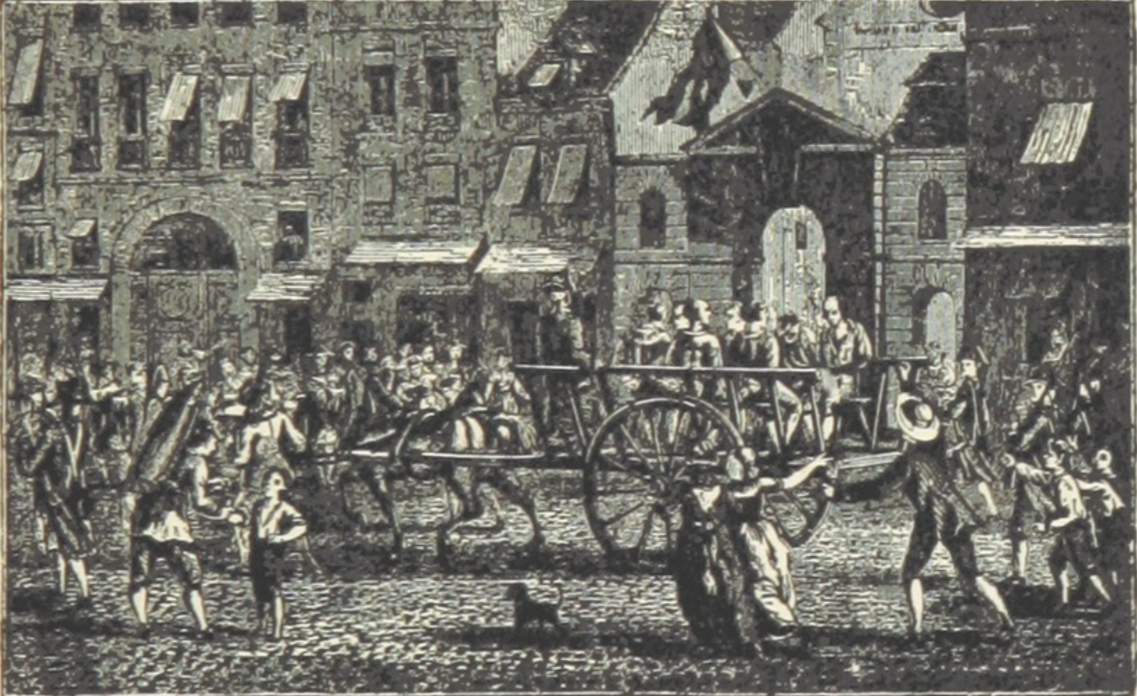

On 8 December 1793, at the age of 50, Madame du Barry was beheaded by the guillotine. Her last words are said to be, “De grâce, monsieur le bourreau, encore un petit moment! (“One more moment, Mr Executioner, I beg you!”). She became one of the thousands executed during the Reign of Terror, including Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

What, then, comes of the young Indian boy who had played a small yet significant role in the most defining event in French history?

Zamor was briefly arrested by the Girondins on suspicion of being an accomplice to the countess. However, when they searched his home, all they found were books and paintings of famous French revolutionaries. As a result, he was released after six weeks in prison and fled from France almost immediately.

We know little about him after that, except that he returned to Paris after the fall of Napoleon in 1815 and spent his remaining days as a school teacher, minus the luxury and wealth that he had unwittingly found himself in the midst of as a child.

He died sometime in the 1820s, nearly penniless, and was buried in an unmarked grave in Paris.

Zamor is hailed as a “traitor of du Barry” among the few who remember his existence and contributions. However, as is the case with most persons of colour who find themselves part of societies that care little for their wellbeing, Zamor’s role faded into obscurity, not just in the present day, but even immediately after the revolution, he devoted his life to.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.