Indian Immigrant’s Winning Formula Helped Create $5.7 Billion American ‘Dream Team’

Using IBM’s computers and statistics, A. Salam Qureishi developed a system that would not only dramatically change the fortunes of the Dallas Cowboys but revolutionise the National Football League (NFL).

At $5.7 billion, the Dallas Cowboys, a National Football League (NFL) team from Texas, United States, is the most valuable sports franchise in the world, according to Statista.

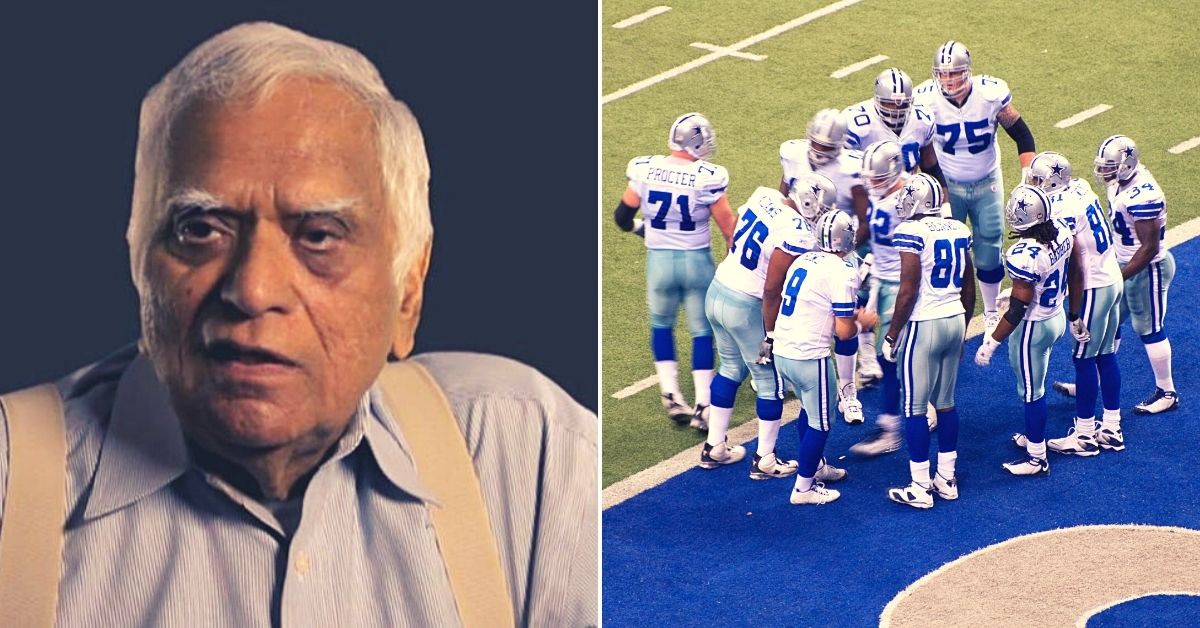

(Image above of Salam Qureishi on the left.)

Established in 1960, the storied American football team were given the five worst players from each of the existing franchises to build their team. Tex Schramm, the president of the Dallas Cowboys, knew this wasn’t going to be the way his team would attain success.

He would have to build this franchise from the ground up through the NFL Draft, which every year selects the best players from different American colleges and drafts them into the NFL.

But how do you scout and select the best college players for your professional team? The answers came from Gil Brandt, a former baby photographer from Milwaukee, USA, who was hired as chief scout in 1960. Two years later, Schramm hired A. Salam Qureishi, a brilliant statistician and computer programmer from a low-income family in Uttar Pradesh, who at the time was working for IBM, the famous technology company.

Using IBM’s computers, sports analytics and statistics, Salam developed a system that would not only dramatically change the fortunes of the Dallas Cowboys, but revolutionise the game. The team established the blueprint for the modern NFL in how teams scouted talent through the Draft process. What we know as the NFL today could not have happened without the contribution of the Dallas Cowboys and their computer whiz — Salam.

Knew Nothing of Football

Born in Singahi village, Uttar Pradesh, Salam grew up poor. It was on the insistence of his mother that he did his Master’s degree in Statistics from Aligarh Muslim University.

In the fall of 1959, he immigrated to the US on a teaching fellowship from the Case Institute of Technology in Cleveland. But shortly thereafter, he was recruited by IBM to work for them in the Silicon Valley. One day in 1962, Salam’s supervisor at IBM called him into his office and asked whether he knew anything about American football or the NFL.

Why was someone asking for him? The answer to this question begins in 1960 when Schramm—who was working for the American TV network, the CBS sports department—witnessed the magic of computers during their coverage of the Winter Olympics that year.

He saw that IBM’s RAMAC 305 computer could process event results in a matter of minutes as compared to hours during past Olympics. He befriended engineers at IBM and asked them a plethora of questions, particularly whether their system could help rank young football prospects. The crew of engineers said yes to Schramm. Two years after taking charge of the Cowboys, he reached out to the people at IBM. His request was simple. He wanted IBM to help him pick new players from the draft for the Cowboys.

Just 26 at the time, Salam was a short man, standing approximately 5 feet 4 inches, with big round glasses and jet black curly hair. More importantly, he knew nothing about football.

Speaking to the Sports Illustrated magazine in 1968, Salam said, “Until I was called to Dallas, I knew nothing about American football. I had learned to enjoy baseball because of its similarity to cricket. Now I think American football is easily the most scientific game ever invented.” Schramm later said, “We had an Indian who knew absolutely nothing about football and coaches who knew nothing about computers and less about Indians.”

Meanwhile, in an ESPN documentary titled ‘Signals: The Cowboys and the Indian’, Salam is heard saying, “I thought football was about people piling on people.”

Revolutionising the Game

When Salam made his way to Dallas, Texas, he would encounter a world that was far away from his humble beginnings. An observant Muslim, who didn’t drink or smoke, Salam was entering the world of NFL, where drinking alcohol and smoking was commonplace. He was entering a state, where as per the 1960 census, there were only 103 Indians.

But Salam was a brilliant mathematician and statistician who knew how to use computers. Before he could work on helping the Cowboys scout the best college players, he needed to learn the rules of the game, different strategies employed by teams, patterns of play and understand the complicated system of player evaluation. Assistance came from Schramm and Brandt, who was also an outsider to the game like Salam, before he was hired.

“Schramm laid out the problem for Salam. Each year, the Cowboys compiled scouting reports on hundreds of players. The team gathered so much information on so many individuals that it was nearly impossible for humans to process it. He also wanted to eliminate the subconscious bias that infiltrated scouting. He knew, for instance, that he loved speed above all else. Give him a fast player, and he would ignore other flaws. That led to mistakes,” notes this report in The Athletic, an online media publication.

In other words, Salaam wanted to gather data on football players and spoke to experts figuring out what makes a good football player. Back then, the basis of judging and scouting a football player was all too subjective and subject to personal biases. Speaking to various coaches, Salam came up with nearly 300 variables affecting their judgment of talent.

Salam told Sports Illustrated that at the time, “The most sophisticated computer system could work with something like only 80 variables. It was immediately evident that we would have to cut down. We reduced everything to five dimensions. But there was a problem of semantics. We had to make sure that the scouts and coaches all meant the same thing when they analysed a player. We had to find keywords that, as much as possible, said what we wanted to know and what the coaches and scouts wanted to say”.

Working day and night with barely any sleep, they came up with five intangible characteristics — character, quickness and body control, competitiveness, mental alertness and strength and explosiveness. And three tangible ones — weight, height and speed.

“You get down this far, then you have to have an accurate measure of all of these qualities,” Schramm explained to Sports Illustrated. “Ask a coach a general question about any one of these qualities and you get a practically meaningless answer. For instance, we used to ask how quick a player was. One coach said he was quick as a cat; another said he was quick as two cats. We had to ask hundreds of questions, trying to find the key phrases that were meaningful both to the coaches and to us.”

The team then hired a psychologist who worked with Salam to design a questionnaire based on these variables. That questionnaire went to scouts from 400 schools and 4,000 questionnaire results came back which were then analysed. This was a time when scouting was just about calling up college coaches and asking general questions about “how about this or that guy”. Soon, the Cowboys trained the scouts on what to do and how to grade a player using this questionnaire with 16 questions. This created a firmer focus.

Questions in the questionnaire were presented in the form of simple statements.

The scout grades a prospect from one to nine on each statement, depending on how well he fits the description. While one was ‘Poor College Ability’, nine was ‘Exceptional or Rare College Ability’. But their main job was to figure out the average or slightly above average players and find out who would fit best in how the team wanted to do things.

“We have discovered that the human mind is not capable of judging degrees on a scale with more than nine ratings,” Salam explained to Sports Illustrated. “You cannot say that this man is one-twentieth more agile than that one or one-twentieth more competitive. So we designed our grading system to fit into the scale of the mind.” Aside from the eight basic qualities, the scout must also rate a player on the specific skills of his position.

“After they devised their questionnaire for scouts, Salam realised they needed to weigh and evaluate the performance and bias of each scout, so they came up with a system for that, too,” notes the report in The Athletic.

In 1964, the Cowboys did a mock draft using Salam’s analytics. After fixing a couple of glitches and technical issues they had it up and running in 1965. Expressing no doubt, he told the Cowboys his system would be “95 per cent accurate”.

In the ESPN documentary, Salam’s daughter Lubna said, “His system was able to pick players that weren’t as obvious to other scouts because he quantified those character traits that made a good football player.”

The team also expanded their search of players from traditional conveyor belts of talent to lesser-known smaller colleges. Cowboys even picked college basketball players who didn’t play football in college but had the characteristics they needed.

Using his system, the Cowboys appeared in five Super Bowls—the final between the two best NFL teams that season—and recorded 20 straight winning seasons, an NFL record.

By 1967, Salam and Cowboys broke away from IBM and formed their own company, but this partnership didn’t last. Three years later, the Cowboys sacked Salam because of business-related issues. This hurt him gravely, but he soon picked himself up.

After refinancing his house, borrowing $60,000 from friends and a bank, he started his own company. He used the computer system that worked out so spectacularly for him in other arenas, including governance, and became wealthy. While Salam thrived, success for the Cowboys slowed down dramatically because other teams also began using computers to evaluate talent, while they failed to fine-tune their own system.

After the Cowboys failed to make the playoffs in 1984, Schramm invited Salam to rejoin them. The statistician worked for a little while before a massive stroke in 1989 seriously affected his health.

Nonetheless, this is the incredible story of an immigrant who came from difficult circumstances and helped an American institution succeed. This problem solver played a key role in helping the Cowboys become the most valuable sports franchises today.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167