These Women Have Taken Ladakh’s Finest Wool From Leh To London Fashion Week

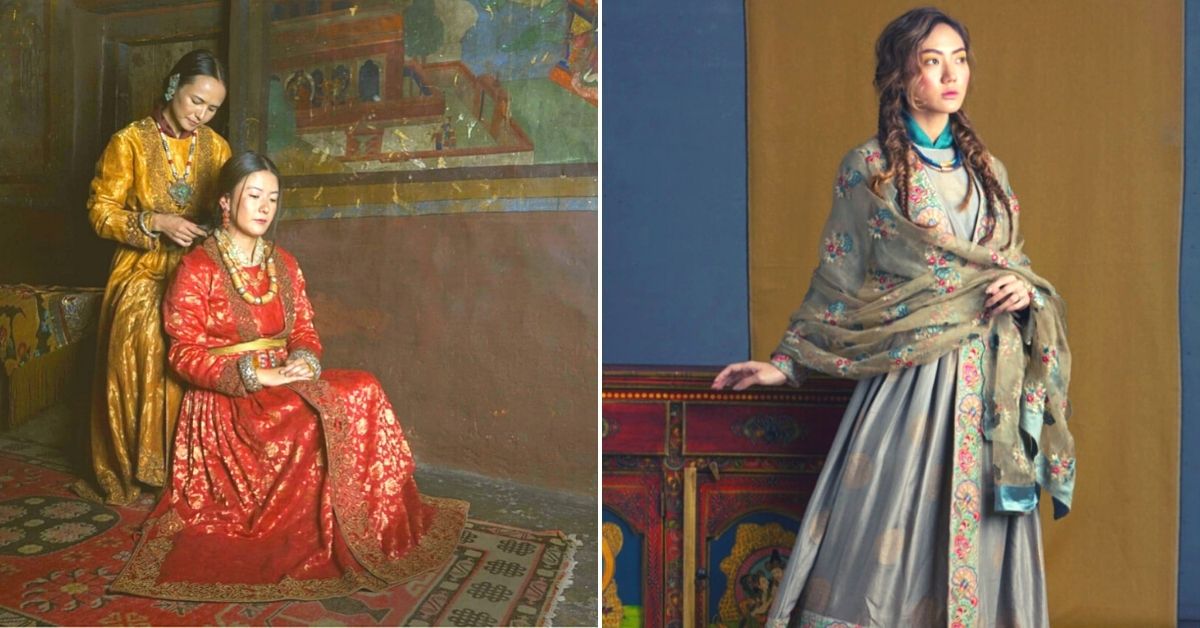

With their apparel brand Namza Couture, Padma Yangchan and Jigmet Disket are pioneering the use of fine Ladakhi textile, whether it's Nambu (sheep wool), Khulu (yak wool), camel wool or pashmina.

Padma Yangchan and Jigmet Disket represent a new generation of Ladakhi entrepreneurs. Coming from relative privilege, these young women see themselves as not only preservers of culture and heritage, but also and more importantly, as creators of wealth reminiscent of a time when Ladakh was an integral part of the global ‘silk route’. Ladakh’s role as a major player in global trading routes has been long lost because of the geopolitical compulsions.

But in ventures like Namza Couture, an apparel brand conceived by Padma and Jigmet in 2016 to create a renaissance of traditional Ladakhi textile heritage, we see the tiny acorns that could one day facilitate Ladakh’s re-emergence as a hub for commerce. In their own words, Namza Couture “advocates curiosity and retains the silhouette of traditional Ladakhi clothing through an additional modern and easy-to-wear design.”

The balance between preserving tradition and furthering its appeal to audiences outside Ladakh is central to what they do. As they note, “By keeping in mind the impact of the silk route in the region, the label strives to keep the Himalayan clothing culture alive by designing on the basis of preserving the original traditional elements. Maintaining a balance between traditional and boldness every garment is made with laborious old techniques.”

Padma and Jigmet are achieving this by pioneering the use of fine Ladakhi textile, whether it’s Nambu (sheep wool), Khulu (yak wool), camel wool or pashmina, with their in-house production of woollen and pashmina fabrics. Another way they are achieving this objective is by using local natural dyeing processes and employing a community-based network of local artisans to handcraft the final garment, which also helps keep their traditional craft alive.

The results of this endeavour have been quite eye-catching. Speaking to The Better India, Padma says, “We were invited to showcase our beloved fabrics and our designs at the London Fashion Week (Autumn/Winter ‘19). It was a great opportunity to showcase the textile heritage of Ladakh like Nambu and Spuruks (textured sheep wool from Zanskar) on an international platform which was highly appreciated by the international fashion media.”

Coming back home

After graduating from Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University, with a Bachelors in Sociology, 31-year-old Padma did a course in fashion designing before finding work in different design houses spread across London, Mumbai and Delhi.

But it was in college, where she first found inspiration. “In college, I did my project on Thikma (a traditional method of tie and dye), which took me on a journey of researching Ladakhi textiles and art. The project was an eye-opening experience for me and I fell in love with the work they were doing back home in Leh. Witnessing the richness of Ladakhi culture and heritage helped me understand the value in working respectfully with artisans,” she says.

For 32-year-old Jigmet, however, the journey was a little different.

After her B.Tech in biotechnology from a Delhi-based varsity, she first encountered traditional textiles as part of an internship with the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO). During this internship, she studied the floral diversity of the Leh area.

“Among the things I studied was how you could use different plants and flowers for natural dyeing. After my internship, I worked at a pharmaceutical company in Delhi, but felt something was missing. That’s when I met Padma. Both of us wanted to come back home and start something. That’s how Namza was born,” she says.

Looking Beyond Pashmina & Working With The Community

There are many ventures in Leh that revolve around leveraging the global appeal of Pashmina, but Namza decided to take a slightly different path with emphasis on Nambu, Khulu and camel wool. With so many players engaged in the business of Pashmina in Ladakh and Kashmir, it takes a lot of attention and effort to make a mark. Instead of taking a similar route, Namza decided to initially focus on Nambu and Khulu.

“Ladakh has much more to offer than pashmina. We have barely scratched the surface in exploring the possibilities offered by Nambu and Khulu,” says Jigmet.

“With our own in-house handloom production unit, Namza is one of the few sustainable design houses to develop a direct relationship with the source itself. Wool sourcing is done mainly from the Changthang region as well as Nubra Valley. Apart from our woollen fabrics we also use cotton, silk, linen which directly comes from different cottage industries in India. Each wool has its own unique characteristics. Nambu is made from indegenous sheep wool and mostly worn in winters to keep the cold at bay. It is heavier in weight and coarser than pashmina. Yak wool or Khulu is one of the most breathable wool as it can absorb moisture and release it into the air. It is coarser than other wool,” says Padma.

Namza’s production needs are met by a community-based network. “We work with around 40 local artisans and ensure a positive impact on the people involved in the supply chain by paying fair wages and investing in the development of rural Ladakh through different handloom projects. It’s a long process from collecting raw materials till the finished products that is why production of garments is not seasonally based,” she adds.

Jigmet notes, “Right from sourcing raw wool to the final garment, the production network in Ladakh is so vast. For example, we source our raw material from one women-led self-help group (SHG) and to wash it, we approach another. Aside from Nubra and Changthang, you can source wool from Choglamsar as well, which is just outside Leh town, where people from the countryside have settled. For spinning, we approach SHGs in Stok village and Phyang village. The winter season is a really crucial time for us, especially for spinners. During the winters, women are willing to take on more work since they have more time on their hands. Their summers are taken up by either tending to their farms or other commercial work. For weaving we approach artisans in different parts of the Leh area.”

Take the example of sheep or yak wool. You have to first wash them with your hands, following which you seperate the down fibre from the yak hair, which is coarser. Yak hair is ultimately used to make the rebo tents for nomads and Challi, a coarse woollen fabric, used to make blankets, rugs and saddlebags. Namza uses the down fibre to make shawls and stoles. After cleaning, you use the carding machine, which also helps in cleaning and intermixes the fibres to produce a continuous web or sliver suitable for further spinning.

“I was initially engaged in the washing process, but as volumes grew, it became imperative to seek assistance from others. Washing the wool requires a delicate and specialised technique. The end product depends on how you treat the wool,” recalls Jigmet.

One of the standout features of Namza Couture-made garments is how they employ the traditional Thikma dye on their garments, notes Padma.

“This process involves resist-dyeing on woollen cloth. The tools used for practising this craft are threads and cords. Thikma is similar to the technique of Bandhani. The colours used are natural dyes made of marigold flower, onion peel, walnut and rhubarb. Thikma was originally exclusive to the Ladakhi royal family, but it was more generally worn from the late 19th century. Thikma has its unique identity in terms of colourful panels, dyed circle and cruciform motifs on a woollen fabric which is confined to the Trans-Himalayan region,” she says.

As a proponent of Ladakhi textiles, Padma personally and meticulously researches and experiments the Ladakhi textiles before translating them into couture pieces. “For the most part, you don’t have to get out of Ladakh to source materials or natural dyes. Each and every village in the Leh area offers its own herbs or plants to make our dyes,” says Jigmet.

Enter Pashmina

Namza sources its pashmina from the Changthang Pashmina Growers Cooperative Marketing Society, which operates a dehairing plant in Leh.

This society and the dehairing plant was set up to primarily protect the commercial interests of Changpa nomads from the Changthang region, who rear the Pashmina goats.

“We source most of our Pashmina from there. With Ladakh obtaining Union Territory status, there is much anticipation that the abundance of funds from the Central government would result in repairing the current dehairing plant and then establishing a new one. If the Pashmina is not de-haired properly, you can’t compete in any competitive market. There are concerns surrounding the functioning of the current de-haring plant in Leh, and hopefully new and improved machinery is installed soon. It’s easier to source from Leh and local rules mandate that you have to buy it from the dehairing plant,” says Jigmet.

While the supply chain for sourcing and dehairing is more well-established in pashmina, that is not entirely the case with wool. “I have seen people from outside Ladakh come and buy tonnes of sheep wool and even arrange for transporting it because of the raw material quality on offer. You don’t really need a dehairing plant for Nambu and Khulu, but this market requires greater organisation,” adds Jigmet.

Garments on Show

Namza creates each piece with sincerity and close attention to detail. It could take a few days or even up to a month to create the bespoke pieces at Namza.

“We are proud to say that the majority of our products are made from scratch. There is a great deal of personal satisfaction in seeing the raw materials turn into priceless pieces of work. Major steps involved in making a piece include focusing on the aesthetics of the design as well as smooth finishes of the end products,” says Padma.

Every region has its own traditional costumes that go back thousands of years, and designers often get inspired by their proud heritage. However, they also want to modernise and make it wearable in today’s time. “There is a continuous need to be versatile and be able to understand the choices of local people as well. And while working on it you always tend to bring your own aesthetics to the table. Being a Ladakhi, I always present some elements in a very subtle way, acknowledging my own rich culture and heritage while balancing traditions with modernity,” she says.

“Foreign tourists often buy our Nambu jackets or flared sleeve capes, whereas locally the demand is for the traditional Kos or Goncha. Interestingly enough, a lot of Indian tourists are looking to buy traditional attire like the Kos or Goncha. Our products are priced from anywhere between Rs 12,000 and up to Rs 5 lakhs depending on fabric, the amount of work and days that go into designing, making, finishing a piece,” notes Jigmet.

Their online presence is limited to Instagram and Facebook and they are working towards building a website. People based outside of Leh can visit their store in Shahpur Jat, Delhi, or they can also order online through Instagram and Facebook. But like most businesses around the world, the pandemic has affected Namza as well. A few of the projects they had planned in 2020 had to be put on hold but they claim to have ensured that their “artisans were least affected”.

Having said that, they are optimistic for the coming year.

That optimism extends to many other young Ladakhis who are coming back home to start various businesses whether it’s in tourism, food processing, apparel wear or something else.

They no longer see Ladakh as merely a place where they return for their summer holidays or family functions. Leveraging the region’s untapped or disorganised resources, ancient culture and heritage, they represent a generation that isn’t satisfied with merely working in secure public sector jobs or running hotels/guesthouses.

Truth be told, this can only be good for the region’s future.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

Similar Story

Beyond Bara Imambara: Heritage Photographer Captures Lucknow’s Hidden History

Maroof Umar loves a good story. Whether it is documenting the last calligraphy artist of Lucknow or finding home chefs who cook the best sheer khurma, here’s how he gives the city’s history a fun spin.

Read more >

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167