Reel Vs Real: Meet the ‘Dead’ Man Behind Pankaj Tripathi’s Character in Kaagaz

Pankaj Tripathi’s movie, Kaagaz is based on the life of Lal Bihari from Uttar Pradesh who was declared dead by the government. He fought a 'posthumous' battle for 18 years to prove that he is indeed alive.

Murda insaan (Dead Man)

Abhi taaza taaza mare, abhi uth ke chal diye (A dead man just got up and left)

This satirical dialogue from Kagaaz, which stars Pankaj Tripathi, was once the reality of Uttar Pradesh-based farmer Lal Bihari Mritak’s life. The film is based on Bihari, who was declared “dead” in the revenue records from 1976 to 1994. He fought a “posthumous” battle against the system and unscrupulous relatives for 18 years to prove that he was, indeed, alive.

At the age of 22, Bihari, a resident of Azamgarh district, learned that his uncle had declared him dead after bribing the local official in order to inherit the family’s ancestral farmland.

“All it took was a bribe of Rs 300 for my uncle to usurp property, and a government official, who was once my friend, to join the enemy camp,” Bihari, now 64, tells The Better India.

Upon realising how easy it was for anyone to take advantage of the legal system and rob someone of their identity using just a piece of paper, Bihari braced himself for a legal battle, and subsequently, spent 18 years of his life to fix this.

In the process, he ended up establishing Mritak Sangh, the Association of Dead People, to highlight the issue and help others. “This was not an isolated case. You’ll be astonished to learn that thousands of people suffer from this bureaucratic inertia every year, which arises from intra-family fraud and diminishing lands,” he says.

Choosing humour over outrage, Bihari did everything – from kidnapping his cousin to bribing a government official, contesting elections, and applying for his wife’s widow pension to enter government records. To that effect, he even marched inside the State Assembly with a placard and shouted mujhe zinda karo! (make me alive).

When death is a beginning

Bihari’s father passed away when he was only a few months old. His mother remarried and moved with her son to Amilo-Mubarakpur from Khalilabad.

Having never gotten a formal education, Bihari learned how to weave Banarasi saris. At 22, he decided to open a loom workshop on his father’s property, which was one-fifth of an acre. He applied for a loan to set it up, but when he approached the district administration for legal permissions, he was denied.

“The officer in Khalilabad, who I had friendly relations with, pronounced me dead while I was sitting in front of him. Very casually, he produced papers that declared me as having been dead since July 30, 1976. The property then “rightfully” went to my uncle. Despite providing all identity proofs, the officer refused to entertain me,” Bihari recalls.

He adds that declaring someone dead is not a challenging feat, especially when the person has not been staying in the village. His uncle managed to prove that Bihari had not been cultivating or occupying the land, and hence, was dead.

After no help from the administration, he approached local lawyers. Some laughed at him, and some extended their sympathies, stating it is a common problem in hinterlands of India.

The news of Bihari’s peculiar “death” spread like wildfire in the village, and so began the mocking. People called him a ghost, and children ran from him. While at first, he was humiliated, with his wife’s support, he chalked out a plan.

His first strategy was to return to government records.

As silly and outrageous as it seemed even then, Bihari kidnapped his uncle’s son, expecting him to register a case. However, when his uncle pressed no charges, he sent his cousin back. Next, he tried to bribe an officer on duty. While handing him money, he requested the cop to arrest him. However, when the copy realised Bihari’s intention, he returned the money.

He also tried availing wife’s widow pension, but all in vain. During this time, he organised his own mock funeral too. “I didn’t want to take this matter too seriously, so I tried keeping my humour alive,” he says.

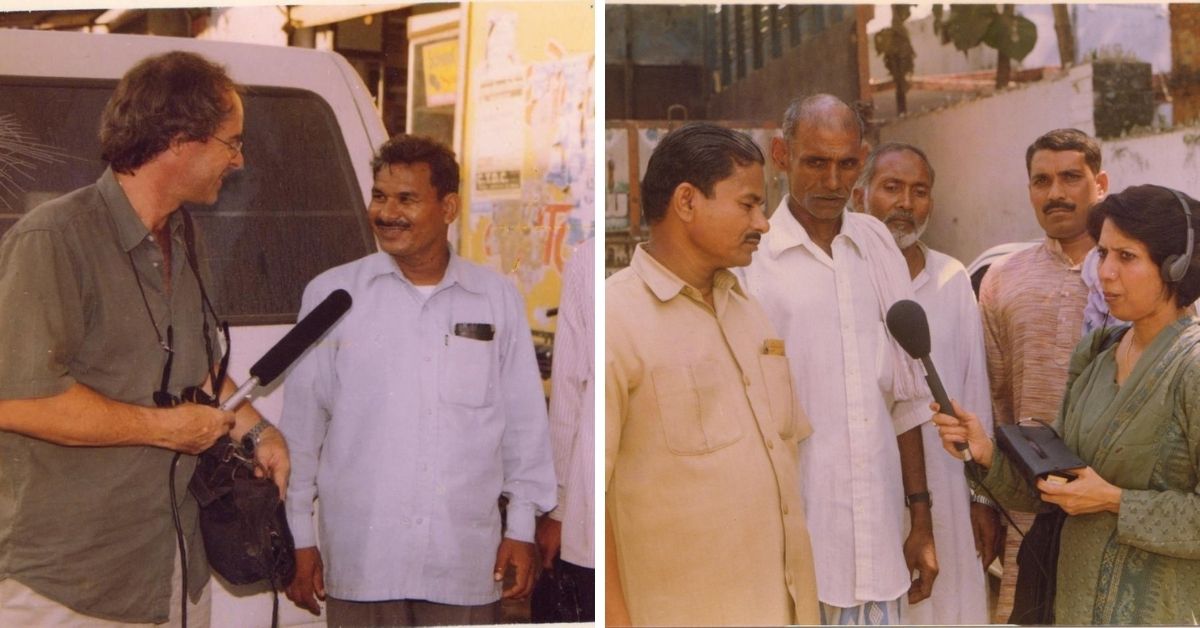

Bihari spent the next couple of months implementing such tactics, which caught the regional media’s attention. Now, he was in the papers, while somehow still being “dead” according to government records.

‘Mritak’

In 1980, Shyam Lal, a politician, reached out to Bihari after reading about him. He told Bihari to openly call himself mritak (the dead), and even use the term as a prefix to his name. From hereon, Bihari began signing his name with the prefix, and only answered when people added mritak to his name.

The same year, he started the Mritak Sangh Uttar Pradesh Association of Dead People, and invited people facing similar issues from across the state to join him.

To get more media attention, he even contested in the state elections in 1988 against former Prime Minister V P Singh. It kind of worked – people heard his story, and nearly 1,600 people voted for him. In the following year, he fought against Rajiv Gandhi in Amethi.

Finally, on 30 June 1994, the district administration fixed the land records and rolled back his “dead” status. Now that he had accomplished his goal, he made peace with his relatives, and allowed them to keep the land.

So why did he give up the land, because of which the entire circus began in the first place?

“I did start the process to launch my career as a weaver, but soon, it turned into a movement. People always said I would never win against the rotten system. They said a common man does not have power against the mighty ones. I said, ‘Let me try’, and the rest is history. As for my uncle, he is still my family, so winning against him would ultimately be my loss,” he says.

Five years after he was “reborn”, the Uttar Pradesh High Court ordered the state government to conduct an inquiry into cases like Bihari’s, and put out an advertisement in the newspaper, asking people to come forward if they had been declared “dead”. A year later, the state recorded 90 such cases, and the National Human Rights Commission was roped in to convene hearings on the matter.

Bihari’s story has inspired thousands of people, and through his organisation, he has helped close to 25,000 people across India.

Today, Bihari lives with his wife and son in Amoli-Mubarakpur, and he is currently focussing on a case he has filed in the Lucknow bench of Allahabad High Court to get compensation. It feels like he has embarked on a similar path – his room, once again, is piling with files and documents.

Featured image source: Satish Kaushik/Instagram

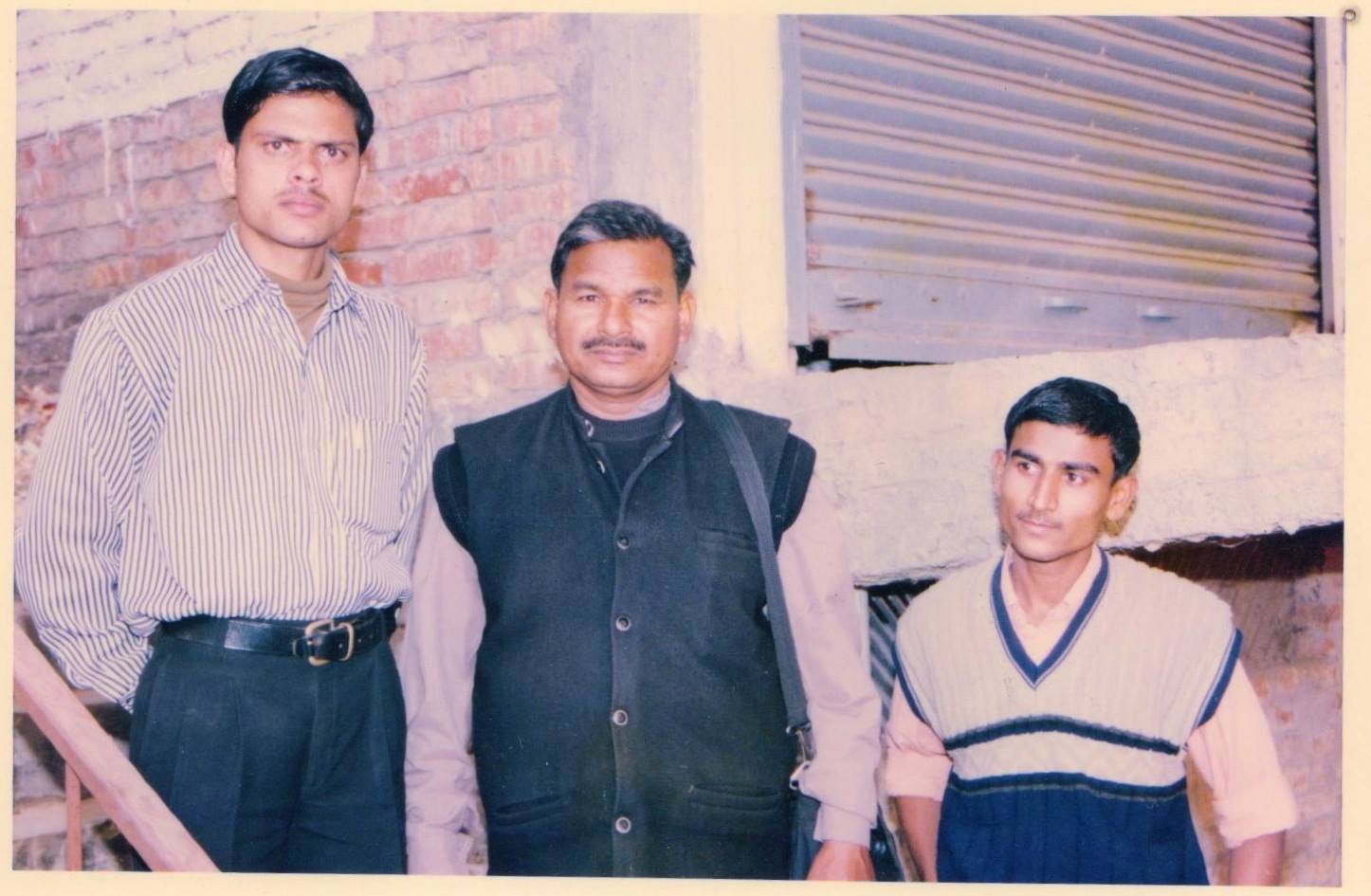

All images are sourced from Lal Bihari Mritak/Facebook

Edited by Divya Sethu

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.